There exists a generation in between Generation X and the Millennial Generation that has been called The Oregon Trail Generation. This is because those of us, myself included, who are of a certain age fondly remember spending hours playing The Oregon Trail. But The Oregon Trail as a game doesn’t belong to just one generation, it belongs to everyone.

It was one of the most popular computer games and a beacon in the educational game industry. It sold over 65 million copies worldwide to become one of the most widely distributed educational games of all time. It was also one of the first simulation computer games. But before we get into how it came to be, let’s take a look at what it is.

For the sake of “research,” I booted up an old version released in 1992 in DOSBox and attempted to make the 2,000 mile journey from Independence, Missouri, to the rich and fertile lands of Oregon’s Willamette Valley.

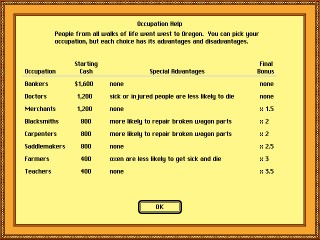

First up you must enter your name and the names of the four other travelers who will accompany you on your journey. Then you select your profession, some of which have special advantages and final score bonuses such as Doctors (“sick or injured people are less likely to die”), Carpenters and Blacksmiths (“more likely to repair broken wagon parts”) and Farmers (“oxen are less likely to get sick and die”).

Based on your selection, you have a certain amount of starting cash to buy your supplies at the store before choosing your starting month and beginning your journey westward.

Now, before I go any further, anyone who has successfully navigated the trail will have their own unique theory on what profession to be and what supplies to buy at the start. I usually choose Doctor, Carpenter, Blacksmith, or Farmer because of their special advantages. Then I proceed to buy my supplies, making sure to buy minimal bullets and food while not skimping on clothes.

This is because hunting, at least in the point and shoot version of the game I played, is easy enough if you only go for the big game and don’t waste your bullets. I’ve also found that later in the game clothing can be used to trade for almost anything. Lastly, I keep some money aside for river crossings.

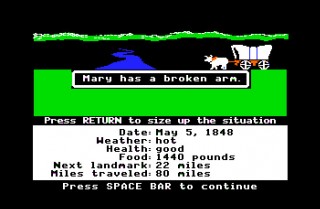

Anyway, once you set out on the trail you’re at the mercy of the random events that can occur.

Some weather related are obvious when they happen. Others, like health issues or taking the wrong trail, happen randomly. All cost you time, whether it’s to wait for the blizzard to pass, getting back on the correct trail, or resting to heal the sick.

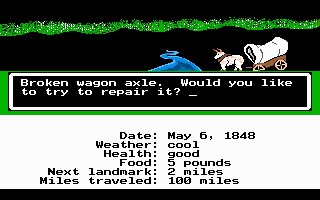

Even more random events can occur like robbers stealing supplies, a fire destroying supplies, oxen running away, or broken wagon parts. You just deal with them when they come and move on.

Trading at stops along the way is a must to replenish supplies used on your journey. Regardless of what profession, supplies or strategy you choose, things will happen. Someone will get bitten by a snake, or have a fever, break an arm or a leg. These events happen in the game because they happened to the real settlers during their migrations.

Along the way at certain landmark stops, you’ll also have rivers to cross. Do you have the money to take a ferry? Will you ford the river or caulk up the wagon and float across?

Outside of the random events and encounters along the trail, river crossings are the most dangerous part of your journey. That is why I always keep money for the ferries. If you can’t afford them and guess wrong at caulking or fording, you run the risk of losing supplies and having your fellow travelers drown. So be careful and choose wisely.

And regardless of how much food you buy at the outset, you will need to hunt at some point. In the original teletype version, hunting was based off of how fast a player could type the word “BANG.” But with the point and shoot versions it is a lot easier.

For all the hours wasted on needless hunting for sport as opposed to hunting for food, remember that as much fun as the point-and-click hunting can be, your ultimate goal is not to kill things, it’s to get to Oregon. And since you can only carry 100 to 200 pounds of food from every hunt back to your wagon, depending on the version of your game, killing more than you can carry is just a waste of bullets and food.

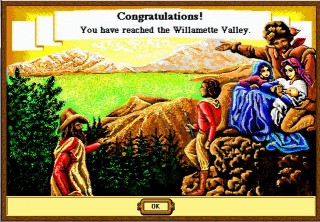

Once you reach the promised land of Oregon’s Willamette Valley, you are given a score based upon your party’s health and remaining supplies. This can be multiplied by a profession modifier to get you your final score.

Now that we’ve covered the gameplay itself from beginning to end, where did this all begin? In Minnesota, of course.

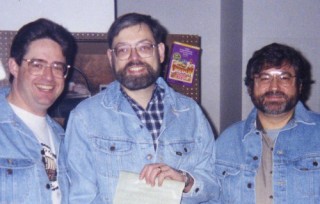

Back in 1971, The Oregon Trail game creators Don Rawitsch, Bill Heinemann, and Paul Dillenberger, were students finishing their degrees at Carleton College.

Rawitsch, in the attempt to get students more engaged in education, started to build a board game about the Oregon Trail. However his roommates, Heinemann and Dillenberger, had other ideas. Despite a fast approaching two-week deadline, the three of them worked to develop the game on an HP Time-Shared BASIC running on an HP 2100 mini computer. This was a teletype computer that didn’t have a monitor and was very much like the PDP-1 that started the hacker evolution in the East at MIT a few years earlier.

Once completed, the game was first played in Rawitsch’s history class on December 3rd 1971. The other two student teachers soon shared the game with their classes as well. But when the semester ended the program was deleted from the computer. Rawitsch to his credit did print out the source code, and it would stay tucked away in his possession for a few years doing nothing but collecting dust.

This is where the history of The Oregon Trail goes from educational gaming software to million dollar business blunder.

In the 1970’s Minnesota was a kind of Midwestern Silicon Valley. Several early computer companies set up shop in Minnesota, and it was because of these companies that the Minnesota legislature proposed the creation of the Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium (MECC) founded in 1973. MECC was intended to “provide computing facilities and support staff to serve the needs defined by education, and available equally to all students and educational institutions in Minnesota on a real cost basis.”

The next year, MECC hired Don Rawitsch. It wasn’t because of his game, although he did bring that with him. After he put The Oregon Trail into their system, it was apparent that this most popular game in their library was something special. In Creative Computing’s May-June 1978 issue, the updated code written in BASIC 3.1 for The Oregon Trail was published and shared with the tech community. This was a time when any tech advancement was shared with the community and also a time when “hacker” wasn’t a bad word.

Next came an important step. When trying to decide where to port the game to next MECC decided to bet on two Steves and their Apple II. This was a boon for The Oregon Trail, its parent company MECC, and the Apple II, which became the educational computer in schools across the country — many of them loaded with The Oregon Trail. This bet on Apple was the right decision at that time, but there would be dark days ahead.

The Oregon Trail’s success was responsible for MECC becoming a public company. And business was great. In the early 90’s MECC invested $1 million in a CD-Rom makeover of the game which made its investment back shortly after its release in 1995.

MECC, the public company, was now starting to spend more time working on the bottom line, overshadowing the educational value of what it was creating. At the same time in the mid-90’s, classroom computing was less of the enterprise it once was because of the burgeoning home computing industry.

Then the wheel fell off, the axle broke, and all the oxen ran away.

Success in the tech industry always brings out the sharks: investors and venture capitalists. And in the case of MECC’s success, this was no exception.

Shark Tank’s Kevin O’leary started Softkey International, a publisher and distributor of software, that was buying up gaming companies in the 90’s like Broderbund, The Learning Company, and eventually MECC, combining them all under The Learning Company banner. The Learning Company was eventually purchased by Mattel in a deal that ended up with Mattel losing almost $1 million after the consolidation and takeover of the former leaders in educational computing.

Meanwhile, back on the ranch, in 1999 the 4th (and last) Edition of The Oregon Trail to come out of Minnesota was released.

The last real updated edition of The Oregon Trail (5th Edition) was released in 2002. It has since been ported over to portable and home gaming consoles, as well as phones and even a short-lived Facebook game. It spawned two official spin-offs, The Yukon Trail and The Amazon Trail. But its legacy is more than just a legacy in gaming. It also has a legacy in computing in general.

Jon-Paul C. Dyson, director of the International Center for the History of Electronic Games said, “The Oregon Trail taught generations of students not only about the history of westward migrations but also how to use computers.” He also said, “it’s hard to think of another game that endured for so long and yet has still been so successful.”

This point is driven home further when you consider that research done “in 2006 found that almost 45 percent of parents with young children knew The Oregon Trail, despite the fact that it largely disappeared from the market in the late ’90s,” according to writer and reporter Jessica Lussenhop.

Rawitsch, one of the original creators, also acknowledged, “despite the lack of graphics [in the original version], students who played weren’t students anymore. They were settlers crossing a wasteland. Their decisions were a question of life or death.”

As one of the first simulation games and, arguably, one of the most successful educational games in history, there were of course some issues as kids will be kids. On early teletype versions, kids poked holes in the code by discovering negative values could add money to their bankroll. And with its meteoric rise in popularity in schools across the country, teachers from all over were asking MECC how to erase curse words from students’ tombstones.

But one thing remains. For everyone who played the game, we all learned what “fording a river” means. We all know that the life of 19th century pioneers on the Oregon Trail wasn’t easy and that success wasn’t guaranteed. We learned while we played, even if we didn’t really know we were learning at the time.

That’s the hallmark of a great educational game; that’s also the legacy of The Oregon Trail.

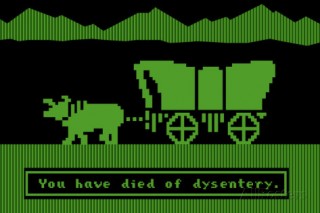

I’d write more about this great game, but I just died of dysentery.