One of the main themes throughout the Battlestar Galactica remake was that “All this has happened before, and all of it will happen again.” When it comes to the now infamous October 30, 1938 Mercury Theatre radio broadcast adaptation of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, this sentiment is completely relevant in our current social media, news-of-the-moment Internet society.

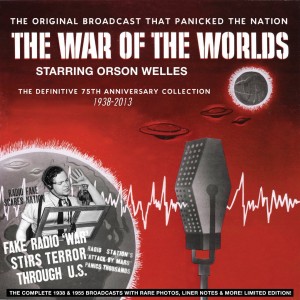

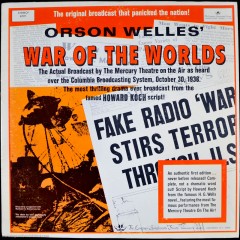

What scared the world, or at least a good portion of the United States, that October night in 1938 was the realistic interpretation of the Wells’ classic science fiction novel that has now devolved into uninvestigated news scares and trending topics on social media, as well as in traditional media, and it’s now happening on a weekly, sometimes daily basis. But before we look into the connection between all of this, let’s look at the history of the broadcast itself.

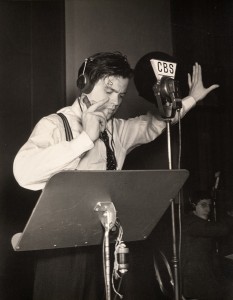

The broadcast aired at 8 p.m. EST that fateful Sunday night. But the story starts around October 22, of that year, after Orson Welles, John Houseman, and Paul Steward selected The War of the Worlds for adaptation, when it was handed to Howard Koch. Houseman selected Koch to adapt the book into a radio play with a directive to convert the story into news bulletins.

On Tuesday the 25th, five days before air, Koch was unhappy with his progress, but Houseman made some suggestions, and by Wednesday there was a completed draft. This was handed to the Mercury actors for rehearsal, but Orson Welles was working on his next stage production of Georg Buchner’s Danton’s Death and had yet to get actively involved.

When Welles finally got involved at the last minute, he revised the script during final rehearsals, just hours before the show was to begin. Welles was a master of ideas under pressure, coming up with the effects and music to make the performance more believable. Because of his last minute rewrites, the first act grew longer than the second act, pushing the station identification break to the 40 minute mark, as opposed to the conventional 30 minute mark.

It seems incredibly hard to believe now, but at that time the Mercury broadcast was unsponsored, compared to today where everything seems to be sponsored. For any who tuned in late to the show, its realism was hard to ignore, given that many people missed the program’s warning that it was an act of fiction, and that there was no station break at 8:30 that night. Something that would have been skipped in an actual emergency.

Interestingly, before the last minute rewrites Welles is quoted as saying the show was “lousy” and a technician said it was “very dull.” But that’s not how it finished. The final version done live on-air was far from “lousy” or “dull.” The panic during the broadcast and its aftermath are well documented as citizens overwhelmed telephone operators and jammed the highways seeking safety.

This kind of public uproar caused the Federal Communications Commission to investigate. Though the FCC investigation found that no laws had been broken, the networks actually agreed to be more cautious with their future programming. But why the uproar for a radio broadcast that started with the announcement “The Columbia Broadcasting System and its affiliated stations present Orson Welles and the Mercury Theater on the air in ‘War of the Worlds’ by H.G. Wells?”

Many speculate that many Americans were listening to NBC, specifically a ventriloquist named Edgar Bergen and his dummy “Charlie McCarthy,” and then flipped to CBS when the sketch ended at 8:12 p.m. which was after the “Martian invasion” had started. This fact always makes me laugh because Americans of 1938 thought that ventriloquism was something to be consumed via radio, a purely audio medium.

The intermission two thirds through the broadcast was “You are listening to the CBS presentation of Orson Welles and the Mercury Theatre of the Air in an original dramatization of The War of the Worlds, by H. G. Wells. The performance will continue after a brief intermission.” But by then it was too late.

Regardless, CBS called a press conference the morning following the broadcast where Welles denied intending to deceive his audience.

During that press conference he was asked straight up by a journalist, “Were you aware of the terror such a broadcast would stir up?” His response “Definitely not. The technique I used was not original with me. It was not even new. I anticipated nothing unusual.”

Although Welles wasn’t entirely responsible for his reaction on that Halloween morning in 1938 (he was functioning on just three hours sleep), subsequent comments made throughout his eventual illustrious career have placed both prestige and blame squarely on his shoulders and given rise to his birth as “the Man from Mars.”

Let us not forget that three years removed from his radio broadcast that scared, and possibly scarred, the nation, Hollywood called and he made Citizen Kane in 1941, which he co-wrote, produced and directed. This was an opportunity that many believe came because of the notoriety caused by The War of the Worlds broadcast.

This story now resonates on a weekly, sometimes daily basis. As Orson Welles orchestrated a larger-than-life “boy who cried wolf” scenario on the radio (the most prevalent media of the time in 1938), so too does it happen today.

Now on a much more regular basis, yet smaller scale “the boy who cried wolf” motif reverberates throughout social media and the internet (the prevalent media of today), even duping 24 hour news channels on television into false reports (television being the predominant media of yesterday).

The Mercury Theatre on Air Presents The War of the Worlds aired in 1938, and today we have seen the “boy who cried wolf” motif on social networks and the internet so often it tends to be laughed at, when called out or not.

“All this has happened before, and all of it will happen again.”

While the motif won’t propel anyone to fame like it did Welles, it’s now so commonplace it doesn’t even garner infamy. Unless you’re the exception to the rule and you work for The Onion.