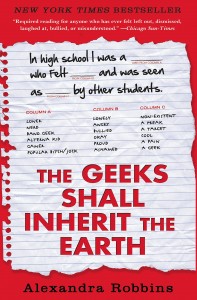

While Alexandra Robbins may be a “Best Selling” author, and she can certainly string her words together, I don’t think she quite reached her goal of explaining Quirk Theory in The Geeks Shall Inherit the Earth.

Essentially, she spoke to multitudes of high school students, teachers, administrators, and parents in order to explain Quirk Theory and how the things that make members of the “cafeteria fringe” outsiders in high school will make them succeed thereafter.

But as a former “cafeteria fringe” outsider (out of the many labels I carried) back when I was in high school, I think the book does some good things – like explain Quirk Theory – and some bad things – like make assumptions and paint “the populars” as the evil to the “cafeteria fringe’s” good.

Using her interviews and the studies of many psychologists as a launch pad, Robbins has one point that is out of place. She writes “…the struggle between individuality and inclusion both adds to the confusion of adolescence and counters likely the strongest lure toward groups that they will ever experience in their lives. Which makes it all the more remarkable when a student is bold enough to swim against the tide.”

But to be frank, in almost every example she states in the book, they aren’t remarkable or bold to swim against the tide. They’re not included and thus the “swim against the tide” metaphor is actually the tide swimming against them. It’s not their choice to be individuals, in most cases. It’s that the group has rejected them and that they have no other option but to be individual and, if they’re lucky, comfortable with themselves.

Robbins tries to drive the point home again, saying that “if there is one trait that most cafeteria fringe share, it is courage. No matter how awkward, timid, or insecure he or she might seem, any teenager who resists blending in with the crowd is brave.”

Again, I say that although the sentiment isn’t necessarily wrong, but I reject the premise that all of the cafeteria fringe or even most of the cafeteria fringe choose to be there. She then goes on to discuss how conformity is a fail safe in our brain chemistry, something we do naturally, which makes not being apart of the group again more a function of the group’s rules of inclusion than you conforming to the group. She seems to be using the wrong facts to prove the wrong point.

Robbins’ comparison of the cafeteria fringe and the current crop of celebrities that used to be them can be misleading. Look at me, for example. I’m a cafeteria fringe person in my own right who did not become rich nor powerful nor famous. The way she writes the book makes it appear that I am the exception and not the rule. Again, we all know that is almost completely false. She’s going for the quick popular assumption about the fringe and unpopular kids in middle and high schools, and she’s using research to back up a failed argument. While the fringe are more widely accepted now through the rapid rise of geek culture, we’re not all smiling all the way to the bank because of it.

And I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that she offended me early on in the book when describing the differences between geek and nerd. “I generally subscribe to the idea that although both groups are known for smarts and social marginalization, nerds might be inclined toward unusual intellectual pursuits, and geeks toward unusual recreational ones.”

There is nothing inherently offensive about what she writes in her quote, but saying that nerds are inclined to “unusual intellectual pursuits,” and geeks to “unusual recreational ones” is kind of offensive. Who is she to judge my pursuits as “unusual?”

This leads me to another issue with the book. Robbin’s objective with the book is that she wants to tell the better story, not necessarily the right story. All appearances – from the student she chose to follow to her conclusions – are chosen based on what would be most exciting or enticing to a broad general audience. They seem like made-for-TV movie caricatures of the stereotypes or labels she’s looking to investigate.

I can only surmise that Robbins herself was a popular kid because she talks and writes about the outsiders as if she’s meeting them for the first time in researching this book.

In no way am I saying she is completely off base with some of her observations. It seems to me, however, that if she had been a “cafeteria fringe” student in her high school days, she would have had a more accurate perspective on Quirk Theory.

She is obviously a gifted writer, and it could just be that this book isn’t for a former outsider who has learned to be an individual. Maybe I’m reading this at the wrong time, or I’m just not the target audience. Both of those things could be more true than not, but judging the book by its cover I was expecting more. I’m not sure what, but I was.

The book is littered with pop-culture, buzzword psychology, including but certainly not limited to:

- “The concept of ‘normal’ has narrowed.”

- “Studies have shown that, at least among students, popularity equates with visibility”.

- “To students who worry that people never outgrow cliquish behavior, it’s important to point out that many–perhaps most– people do.”

- “Self-awareness is an authenticity of being. It is a commitment to the values and philosophies that you have already figured out are important to your individual identity. It is an understand of what will make you happy, successful, respected, or valued.”

- “Although so many students have the same things to say, they cross signals in a maelstrom of misinterpretation, then lose sight of each other behind their stereotypes.”

These are all statements that I could have reached without research, because I was an outsider myself.

Her last statement in the book, surprisingly, is solid.

“Unshackled by strict yet arbitrary, misguided norms, outcasts can be, look, act, and associate however they want to. And in this ever conformist, cookie-cutter, agazine-celebrity-worshipping, creativity-stifling society, the innovation, courage, and differences of the cafeteria fringe are vital to America’s culture and progress. Which is why we must celebrate them.”

We should celebrate those who are different, but how she reached that conclusion, in my view, lessens its impact.

This isn’t necessarily bad book. I just think it was written to intrigue the lowest common denominator, which seems to contradict the idea of celebrating the outsiders. For one thing, that wouldn’t have sold nearly as many books.