Despite the fact that Console Wars by Blake J. Harris is about Sega rising to the top to dethrone Nintendo before slowly, painfully, and publicly falling out of consoles all together, this book is mainly about marketing, big ideas, and Tom Kalinske.

Now, I don’t mean that as a slight. Kalinske is a fascinating individual; the man came up with He-Man when he was at Mattel, after all. But the book does generally paint Nintendo as the bad guy despite the fact that Nintendo ultimately wins or at least won the 1990s.

But I’m glad the author took the time to go back and set the stage when necessary, because of all the stories worth telling, this one regarding Sega vs. Nintendo is important. Because without Sega, Nintendo wouldn’t have been pushed to be better. Competition truly does bring out the best in all of us.

Let’s talk about Kalinske. He’s not the every man. In fact, he’s smarter than the every man, but just as explained in the book, Sega’s failure was not Kalinske’s fault, not entirely. Ultimately it was cultural differences that did Sega in. It was the internal struggle of Sega of America versus Sega of Japan that did in the company, which Al Nilsen, one of the marketing forces behind Sega of America’s rise to the top, realizes is due to “the fundamental difference between Sega of America and Sega of Japan. They weren’t willing to take the risk, to race Sonic against Mario or welcome a generation to the Next Level. These people were highly talented and certainly not lazy, but deep down they weren’t as interested in winning as they were in not losing.”

But Nilsen and the others that Kalinske put together were the best team at the perfect time to take on the industry giant. Nintendo was the only real game in town when Kalinske took over Sega of America, and despite the fact that he lost the Second Generation War, he and his team arguably won the 16-bit War.

One other thing of note before I move on beyond Kalinske: he was instrumental in helping to facilitate the creation of the Entertainment Software Rating Borad (ESRB), which was in part because, at Kalinske’s urging, Sega had implemented its own voluntary ratings system, the Videogame Rating Council (VRC), which was ahead of its time and not required at that time at all. Of everything Kalinske had his hands in, being instrumental in helping to create the ESRB is something that, despite the nostalgia people have for the Sega Genesis, is something that will always endure.

One other thing of note before I move on beyond Kalinske: he was instrumental in helping to facilitate the creation of the Entertainment Software Rating Borad (ESRB), which was in part because, at Kalinske’s urging, Sega had implemented its own voluntary ratings system, the Videogame Rating Council (VRC), which was ahead of its time and not required at that time at all. Of everything Kalinske had his hands in, being instrumental in helping to create the ESRB is something that, despite the nostalgia people have for the Sega Genesis, is something that will always endure.

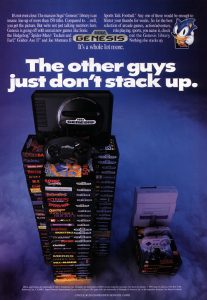

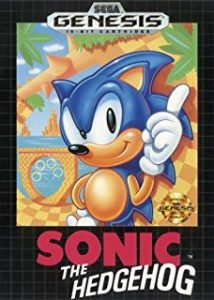

This book, as I mentioned, is also about marketing, because arguably it was the silver bullet of marketing; Sonic versus Mario, “Welcome to the Next Level,” the mall tours, flashy ads, and fanfare, that helped Sega grab more market share than Nintendo.

It’s also about one other thing, that Harris describes very well.

“It’s all about cool; that’s the holy grail. You’re born, you die, and in between you spend a bunch of years search for it–looking cool, sounding cool, buying cool, and, no matter what, not being uncool. That right there, that’s the secret formula. It’s addictive, it’s enlightening, and it’s goddamn recession-proof. In a world full of too many people shouting too many things, it’s the only adjective that really matters: ‘cool.’”

But “cool” can only take you so far. In the rush for the future moving from 16 bits to 32 and 64, that’s when Sega faltered. As we know, now more than ever, it’s never easy to jump to the next generation. In today’s tech heavy markets, it’s becoming commonplace, but it wasn’t so much so back in the nineties. That leads to one of the important lessons in this book. Is it about being the first to get there or is it about being the best? This is an argument that is actually settled within the book. It is about the slow game of being better because, unlike a true race, it’s not always about being first.

Overall video games are much more mainstream than they used to be, but it’s still a club. Regardless of the games you play, you either are a gamer or you aren’t.

“Whereas secret societies in the past have met in lodges, taverns, and dimly lit alleys, this new generation’s meeting spot was the virtual world of videogames. And also unlike the covert gatherings of yesteryear, where furtive glances and secret handshakes were needed to gain entry, the only password into this world was up-up-down-down-left-right-left-right-B-A-start. Playing videogames wasn’t even so much about being good at them as it was about understanding them in a fundamental way that adults never could. For the first time ever, the kid who could never beat his father on the basketball court or beat his mother in an argument now had a place where he could reign supreme.”

And this makes more sense to me than anything else. As a kid who asked for an NES, before Sega even existed, I received instead an IBM PC running DOS. And while that has been one of those seminal moments that put me on a path towards the knowledge I have today and the things that I do, I will never forget sitting on the floor of my friends living room passing the controller back and forth as we blasted through Super Mario Bros. Despite not owning a video game console until the GameCube, I still shared the experience with friends through their consoles. Since it’s about understanding much more than it is about winning, then watching (and even the sharing) is as much a part of the process to that understanding as anything else.

As the Game Master himself, Howard Phillips, is quoted in the book, “…there are so many messages out there surrounding videogames that it’s important for me to step forward and present a positive message. Play itself is very rewarding for children. Maybe in some respects there’s a little too much play, but play is still important. And there’s this whole social opportunity, this currency of interaction, with friends, family, and even strangers. That kind of attitude extends beyond the playground, so I was really happy to be expressing that aspect of games.”

And in the end, and speaking as one of the kids that was of this generation, Sega versus Nintendo really was a battle that defined our generation.

It was a revolution. “The revolution had indeed been pixelated; videogames were not just a fad, not just for kids, but a source of art, story and entertainment for anyone of any age at any time.”

This book is for anyone who wants to know about marketing and/or videogames. If you have any shred of Sonic versus Mario nostalgia, this is a must read, regardless of which side you were on back then. Larger than the book itself is the fact that this battle became something else. As Kalinske said at the first E3, “We’ve broken out to become a whole new category, a whole new culture for that matter. This business resists hard-and-fast rules. It defies conventional wisdom.”

This book is for anyone who wants to know about marketing and/or videogames. If you have any shred of Sonic versus Mario nostalgia, this is a must read, regardless of which side you were on back then. Larger than the book itself is the fact that this battle became something else. As Kalinske said at the first E3, “We’ve broken out to become a whole new category, a whole new culture for that matter. This business resists hard-and-fast rules. It defies conventional wisdom.”

I commend Blake J. Harris on the work of Console Wars, a book that taught me more than I thought it would. And it will do the same for you.

Read the Secret File of technical information and quotes from Console Wars by Blake J. Harris.