I always read through entire books. I’m not saying that to be a snob, but most Acknowledgments at the end of a book, give you a glimpse into a short commentary on the book process itself. However, I was thrown for a loop when I was reading the Acknowledgements of Bomber by Len Deighton, when I read the sentence; “This is perhaps the first book to be entirely recorded on magnetic tape for the I.B.M.72IV.”

Deighton’s modesty aside, “this is perhaps,” is definitely modest, the sentence was something that I couldn’t just read, it had to be looked into. And when I looked into it, I found an article by Matthew Kirschenbaum an associate professor of English at the University of Maryland. At the time he was working on a book titled; Track Changes: A Literary History of Word Processing, which is now published.

Now, the article is brilliant, and I’ll add the book to my wishlist, behind the dozens of books, I still have on my bookshelf, that I have to read, and I don’t want to just rephrase his story here, but there are some things, historically, that I want to comment on…

First, let’s look at the original quote from the Acknowledgements, the entire paragraph that Deighton devoted to process;

“Mr. Jacques Maisonrouge of I.B.M. must be thanked for his authoritative aid. This is perhaps the first book to be entirely recorded on magnetic tape for the I.B.M.72IV. This has enabled me to redraft many chapters over twenty times, and by means of memory coding to select certain technical passages at only a moment’s notice. Ellenor Handley has operated this machine and given her expert and detailed attention to the MS at all stages as well as providing a cross-reference system that, together with color coding and reference cards, has enabled me to find my way around this very long book.”

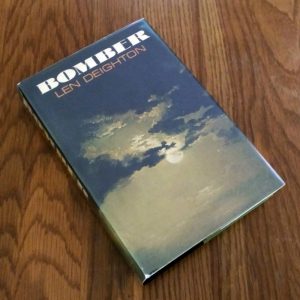

Bomber by Len Deighton

It’s easy to overlook this process of including a computer, or in this case a word processor, into the creation of a book. Especially in a day and age when the written word is hardly written. It’s usually typed, even in the face of “writing” and “reading” going somewhat out of style with the rise of audio books and computer dictation.

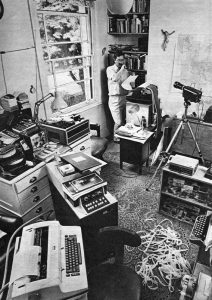

Bomber was first published on September 10th, 1970 and Deighton first had the I.B.M. installed in his house in 1968. This was well before personal computing was a thing, and at a time when this particular word-processor could only be installed into Deighton’s house by removing a window. Now, word-processing is just a fraction of what our computers and even our phones can do. It’s just a part of them, and we don’t need to renovate our homes to get them inside.

Even more to the point it’s what we take for granted in word-processing software that was most appealing to Deighton.

“One might almost think the word processor (as it was eventually named) was built to my requirements. I am a slow worker so that each book takes well over a year—some took several years—and I had always ‘constructed’ my books rather than written them. Until the IBM machine arrived I used scissors and paste (actually Copydex one of those milk glues) to add paras, dump pages and rearrange sections of material. Having been trained as an illustrator I saw no reason to work from start to finish. I reasoned that a painting is not started in the top left hand corner and finished in the bottom right corner: why should a book be put together in a straight line?”

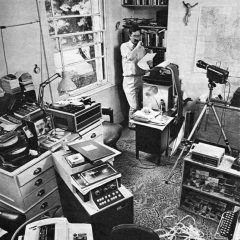

Len Deighton and his IBM word processor, London, 1968.

Now, we’ve all added paragraphs and moved them around, cut, copied, and pasted text. But the ease of use is so familiar that we don’t think twice, because it can be done almost anywhere, in a browser or in a program, and even in cloud software. Even more phenomenal than us taking this for granted is that it was happenstance that put Deighton and the IBM together in the first place.

To quote again from the beginning of Kirschenbaum’s piece, “It was 1968, and the IBM technician who serviced Deighton’s typewriters had just heard from Deighton’s personal assistant, Ms. Ellenor Handley, that she had been retyping chapter drafts for his book in progress dozens of times over. IBM had a machine that could help, the technician mentioned. They were being used in the new ultramodern Shell Centre on the south bank of the Thames, not far from his Merrick Square home.”

So, if the technician hadn’t mentioned it or if Ms. Ellenor Handley hadn’t said anything, I might never had (in my own happenstance) read the book that was the first done on a word processor.

Again, I can’t speak highly enough of Kirshenbaum’s article, and I look forward to reading his book, which I can most assuredly presume was written on a computer.