Before I get into this book and its subject (Claude Shannon), I must borrow from the authors in their acknowledgements, because they have succinctly described the reason that I picked up this book and others, like Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution, Where Wizards Stay Up Late, even Masters of Doom, countless others on tech innovators like Bill Gates, The Steves (Jobs and Wozniak); and will continue to do so.

“…it is not the Internet that is unnatural, nor our feast of information, but a refusal to consider what their origins are, how and why they are here, where they sit in the flow of our history, and what kinds of men and women brought them about. We think there is something of an obligation in beginning to learn these things. We think that the honor our subject would have cared about–if he cared at all–would not have been adulation, but a bit of comprehension.” I couldn’t have said it any better myself and I have made attempts.

Now on to the book itself. The authors and I can’t agree with them enough, have already given you reason enough to open its pages.

There is something special to the mind of a genius. More special perhaps than the individuality we all have because otherwise, we’d all be geniuses. Biographies of genius, and of talented people not quite on that level, all give you a glimpse into the mind of their subject and “A Mind at Play” by Soni and Goodman is no exception.

I read plenty of non-fiction, but this is the first book I’ve read in a long time that took me to school. Not in any kind of condescending way, but in order to fully understand what Claude Shannon did, you need to actually understand the math.

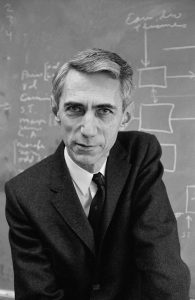

Claude Shannon

But there is much more to Shannon than math and engineering. “Shannon’s body of work is a useful corrective to our era of unprecedented specialization. His work is wide-ranging in the best sense, and perhaps more than any twentieth-century intellect of comparable stature, he resists easy categorization. Was he a mathematician? Yes. Was he an engineer? Yes. Was he a juggler, unicyclist, machinist, futurist, and gambler? Yes, and then some. Shannon never acknowledged the contradictions in his fields of interest; he simply went wherever his omnivorous curiosity led him. So it was entirely consistent for him to jump from information theory to artificial intelligence to chess to juggling to gambling–it simply didn’t occur to him that investing his talents in a single field made any sense at all.”

Beyond the math and the theories, Shannon is quite the subject for a biography and as is not always the case, a biography of Shannon must have been a thrill to research.

From the inspiration for Information Theory and the most important creation therein of the “binary digit” or “bit” that is the foundation of our current digital world to genetics, robotics, juggling, and much more; a look into Shannon is something special.

Despite the book being about Claude Shannon, something emerges that can’t be ignored. To read this book is to take a journey through history and understanding. There are insights that the authors do well in calling out, that although all relate to Shannon, could very well stand on their own merits as well. I will cite which are from the authors and which are from the subject Shannon, because they all flow well together within the book, but could all use a little more of our thought.

It turns out that some of the most childish questions about the world–”Why don’t apples fall upwards?”–are also the most scientifically productive. – The Authors

“Seldom do more than a few of nature’s secrets give way at one time.” – Claude Shannon

“I think the history of science has shown that valuable consequences often proliferate from simple curiosity.” – Claude Shannon

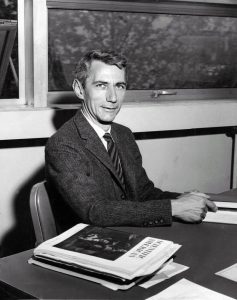

Claude Shannon at work

“A very small percentage of the population produces the greatest proportion of the important ideas.” – Claude Shannon

It was, at least, a refreshingly unsentimental picture of a genius: a genius is simply someone who is usefully irritated. – The Authors

Simplicity matters. Elegant math was forceful math. Inessential items, superfluous writing, extra work–all of them should be discarded. – The Authors paraphrasing what they learned from Shannon

“…the value of finding joy in work. We expect our greatest minds to bear the deepest scars; we prefer our geniuses tortured. But with the exception of a few years in his twenties when Shannon passed through what seemed like a moody, possibly even depressive stage, his life and work seemed to be one continuous game. He was, at once, abnormally brilliant and normally human.” – The Authors

Simply put, this will henceforth be one of the books I can’t shut up about when people ask for recommendations. If you enjoy anything at all about the digital age we live in, go out and get yourself a copy of A Mind At Play: How Claude Shannon Invented the Information Age by Jimmy Soni and Rob Goodman. You should know how these things that bring you joy, or money, or allow you to communicate easily have come into being. And for all of it, you owe a debt of gratitude to the man who is the subject of this thoroughly well-written book; Claude Shannon.

For additional information, I suggest you listen to The Internet History Podcast “Claude Shannon, Father of Information Theory” in which host Brian McCullough discusses Shannon with authors’ Jimmy Soni and Rob Goodman.