Coffee has a rich, bold history, with all the ingredients of a well-produced premium cable miniseries: kings, spies, pirates, lovers, religion, politics, and war.

Over the years, its advocates and acolytes have called it “koffie,” “kahve,” “qahwah,” “quwwa,” “kaafa,” and “cafe,” and the path it took to your kitchen counter is rife with treachery, battles, seduction, and dumb luck.

Pre- 1000s

Some sources say coffee was being cultivated in Yemen as early as 575 A.D. and that unroasted berries from the coffee plant were brewed to make a weak coffee in Mecca and Cairo. But the legend of Kaldi is the most common beginning to the history of coffee.

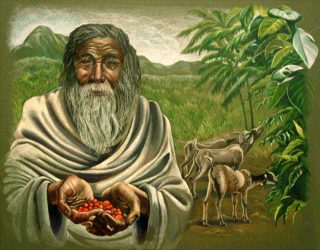

The Legend of Kaldi

Kaldi, an Ethiopian goat herder, notices his flock is more energetic and playful near a certain bush. Realizing that the goats had eaten berries from the bush, Kaldi takes a sample, gets a boost, and gifts humanity with the coffee berry.

Kaldi tells the abbot of a local monastery. The abbot thinks these berries are the Devil’s work and throws the berries into the fire. But a hero in the form of a rebellious young monk snatches the hot beans and mixes them with water, resulting in the first cup of coffee, with roasted beans, in recorded history. (Yes, the old stories of coffee intermix berries and beans in the telling.)

Word of the berries travels to the Galla tribe, and they mix them into a power bar of sorts. Because these were berries, they called them “magical fruit.” And for the next period of time, only select tribes, traders, and adventurers knew of these “magical” berries.

1000s

It took some time for word to travel back then, but eventually Avicenna Bukhara writes down the first passages describing coffee of its medicinal purposes. Avicenna writes, “It fortifies the members, it cleans the skin, and dries up the humidities that are under it and gives an excellent smell to all the body.”

1100s

Arab traders start returning to their homelands with the beans. They cultivate the plant for the first time on plantations, and mass production of coffee starts all the way back here. They, too, drink the beans by boiling them in water. They call it “qahwah” or “that which prevents sleep.”

1400s

Eventually, coffee finds its way to Constantinople (now Istanbul), where the Turks add clove, cardamom, cinnamon and anise, which is something they still drink to this day. As a center for culture and a large trading metropolis at this time, word of coffee spreads from the streets of Constantinople beyond its borders as traders and travelers alike get their first sips of the beverage in the city.

Enter Mufti of Aden, who “found that among its properties was that it drove away fatigue and lethargy, and brought to the body certain sprightliness and vigor.”

Illustration of Mecca (circa 1907)

In Mecca, thanks to the Mufti’s approval, the first coffee houses, called “Kaveh Kanes,” are established. They begin as spots for religious meetings, but soon storytelling, rumours, gossip, and singing follow.

A few years later, coffee shops are open for business in Constantinople, and as in Mecca, these too are places of lively discussion and debate.

The Turks take their coffee so seriously at this point that they create a new law making it legal for a woman to divorce her husband if he fails to provide her with a daily quota of coffee. At this time, coffee is widely believed to be an aphrodisiac. (I’ll let you put 2+2 together here.)

1500s

Too much talk. The Governor Khayr Bey bans coffeehouses in Mecca, fearing opposition to his rule. His ban shuts down shops as far as Constantinople, but cooler heads prevail after the riots and unrest that would no doubt result from a lack of the citizens’ access to coffee. Eventually the sultan of Cairo sends word that coffee is sacred and has the governor executed. The lesson here? Don’t mess with coffee.

“O Coffee, thou dost dispel all care, thou art the object of desire to the scholar.” – An Arabic poem from 1511

This isn’t to say coffee was golden. Even in Cairo, a ban was enacted; perhaps that ban’s negative impacts on society allowed the sultan to learn from his mistakes. It’s an early example of the refrain from Battlestar Galactica: “All of this has happened before and will happen again…”

Later in the century, coffee arrives in Venice. At first the venetians only make this rare and exotic drink available to the extremely rich, but that doesn’t last. Soon venetians of all classes partake in the consumption of coffee.

The 15th Century comes to a close with Arabia and Africa holding a firm monopoly on the drink. But their trade between the Republic of Venice and those coffee-holding nations was so strong at the time that further spread of the coffee was inevitable.

1600s

In order to keep their monopoly, the coffee-producing nations enact laws that forbid the export of fertile beans. Ah, the best laid plans…

The city of Mecca is a pilgrimage for Muslims to take. As such, many travelers are introduced to coffee during their holy pilgrimages at this time. One Asian Indian named Baba Budan smuggled out some fertile beans under his shirt and secretly cultivated the beans in India. “Old Chik,” as the beans are called, is responsible for about a third of the total coffee production in India today. Budan was made a saint and even has a region of India named after him. Coffee is quickly becoming a “hot” commodity, but it’s not all smooth tastings.

The city of Mecca is a pilgrimage for Muslims to take. As such, many travelers are introduced to coffee during their holy pilgrimages at this time. One Asian Indian named Baba Budan smuggled out some fertile beans under his shirt and secretly cultivated the beans in India. “Old Chik,” as the beans are called, is responsible for about a third of the total coffee production in India today. Budan was made a saint and even has a region of India named after him. Coffee is quickly becoming a “hot” commodity, but it’s not all smooth tastings.

In Venice, the church starts to believe that the popularity of coffee means it must be no good. Believing it to be “satanic,” Pope Clement VIII has a taste of this “devil’s concoction,” but after a taste proclaims, “Why, this Satan’s drink is so delicious that it would be a pity to let the Infidels have exclusive use of it. We shall fool Satan by baptizing it and making it a truly Christian beverage.” This marks the second time in its history that coffee has been marked as “evil,” and it will not be the last.

Let the trading and exploring begin! British adventurer and explorer Captain John Smith, a founding member of the Jamestown Colony whom you may remember from the story of Pocahontas, writes of “coffa” the Turkish drink in his bestselling book of the time, Travels and Adventure.

Next up, the Dutch get their first sip of coffee as trader Pieter Van Dan Broeck, of the Dutch East India Company, tastes the drink on a visit to Mocha in Yemen. Pieter successfully smuggles out a fertile seed, but the Netherlands climate isn’t conducive to cultivation. Undeterred, the Dutch soon expand their trading from spices to include coffee.

University of Oxford

Finally, coffee comes to England with the help of Nathaniel Conopios, a Greek student who brews the first cup of coffee in the country at the University of Oxford. Although the coffee-enabled all-night partying gets him thrown out of the prestigious University, the coffee remains.

Now, coffee houses open in Italy and England. But near Oxford, some Englishmen create the Oxford Coffee Club, which helped foster theories and ideas among students and scientists alike. Later, that club would become the Royal Society. The Royal Society still exists today as a “learned society for science” and functions as the United Kingdom’s and Commonwealth of Nations’ Academy of Sciences.

Those coffee houses in England soon become known as “penny universities” as they fill up with a cross section of humanity, from traders to students to the elite of society. The only people missing are women, who at this time aren’t allowed in these “boys only” clubs. Eventually the women protest and are granted access to the discussions happening at the penny universities.

Continuing its conquest of the world, coffee enters Austria as the first coffee house opens in Vienna following the Battle of Vienna, using the spoils of war from their defeat of the Turks.

Meanwhile, the Dutch, looking to secure a monopoly over cinnamon, take over Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) from the Portuguese. Luckily for them, they not only take over cinnamon, but a small cultivation of coffee crops, which the Portuguese had conquered earlier from the Arabs. What’s a little thieving among thieves—or in this case, conquering among conquerors?

Back in London, public drunkenness is a large issue. As a result, coffee houses start replacing bars and taverns as the place to meet. Though this curbs the public drunkenness, owners of the bars and taverns, seeing their profits fall, attack coffee. They make a religious appeal to the nature of coffee in relation to beer, arguing that Christian monks have been drinking and brewing beer for centuries, while coffee, with its Arabic roots, is not Christian at all.

Coffee brought us the tradition of tipping.

But the taverns and bars will eventually reap the rewards from a financial innovation brought on by coffee as boxes labeled “To Insure Prompt Service” are placed in English coffee houses, drawing patrons’ coins. That’s right: Coffee brought us the tradition of tipping.

In 1669, France finally gets a taste of coffee when Suleiman Aga, the Turkish ambassador to Paris, brings coffee into the Court of Louis the XIV. But before all of France can enjoy a cup of “cafe,” a class war occurs as the elite Parisians believe coffee is for the lower classes. Eventually, they relent, and shop owners open lavish elegant shops and offer tea and chocolate in addition to coffee.

Remember the Governor of Mecca who attempted to banish coffee? King Charles II orders all of England’s coffee houses closed for fear of revolution. Apparently, coffee houses, these “penny universities,” encourage ideas and talk that might lead to revolt. Protests in the face of this action are so severe that the ban lasts only 11 days.

Now we come to Franz, a story of incredible odds, and the origin of Viennese coffee. In 1683, the Turks and their army of 300,000 were on the verge of taking Vienna during their second siege of the city. Though their numbers were many, a young Pole named Franz Georg Kolschitzky turned the tide on the Turks.

Franz offered his clandestine services and infiltrated the Turkish Army for vital strategic information. With this information, the defending Austrian army led by the Prince of Lorraine, attacked and sent the Turks running.

The spoils of victory were beyond grand: 25,000 tents, 10,000 oxen, 5,000 camels, plenty of gold, and 500 sacks of coffee beans. All of the spoils were divided except the coffee, which no one wanted except for Franz. As the hero, Franz is awarded the coffee, Austrian citizenship, and permission to open the first coffee house in Vienna, the Blue Bottle.

Battle of Vienna

At first business was slow, as the Viennese did not enjoy the coffee the way that Franz had learned to make it during his time in Istanbul. But Franz was a smart man who decided to make some changes. He filtered the coffee and added cream and honey to the drink, and the Viennese took notice. Thus, Franz’s business took off, and Viennese coffee was here to stay.

Continuing this tradition worldwide, cream being added to coffee naturally lifts the flavour and reduces acidity. Most world-class coffee drinkers in fact don’t drink theirs black, but rather with a splash of cream.

In 1686, Cafe Procope, the first “literary” coffee shop, opens in Paris, where it remains in business to serve customers as it once served Voltaire and Napoleon. In fact, as a young lieutenant, Napoleon had to settle a bill by leaving behind his hat. I wonder how much coffee his hat was worth?

Anyway, the trade wars are starting to heat up as the Dutch finally break into the monopoly on coffee. The Dutch influence will heavily impact the transport of coffee across the ocean to the “new world.”

But before the 1700s can begin, in London, Johnathan’s Coffee House begins listing stock and commodity prices, and the London Stock Exchange is born in 1698.

1700s

Early on in this century, the French start making coffee with the grounds in an enclosed linen bag. No more grinds. Just keep that in mind the next time you complain about the one or two that your coffee maker lets through. For almost the first millennia of coffee’s existence, there were always grinds in your cup.

Royal Botanical Gardens in Paris

Now coffee, especially in fertile seed form, is an exquisite gift, so much so that the mayor of Amsterdam gives a young coffee plant to King Louis XIV of France, who places it within the Royal Botanical Gardens in Paris. Because clearly, if you can’t show off, what’s the point?

In Germany, the coffee trade expands beyond coastal trading ports such as Bremen and Hamburg to the German capital of Berlin, which finally gets its first coffee house.

Back in Paris, remember the gift of the coffee plant that is now sitting in the Royal Botanical Gardens? It’s grown into a full coffee tree, and it’s about to get snipped.

At first, Gabriel Matthieu de Clieu, a French Naval Officer on leave from Martinique, simply requests a few clippings from the tree, believing that the plant would thrive in the Caribbean climate. But the king denies him outright. Undeterred, Gabriel remains as a guest of the court enjoying wine, women, and song.

Eventually, Gabriel scales the walls of the Royal Botanical Garden and “snip snip” makes off immediately to set sail back to Martinique. But the journey is perilous. He tends the plant in a glass cabinet, bringing it on deck during the day and protecting it below deck during the night for weeks without incident, until one day a crew member pulls a dagger on him.

Though the crew member was able to cut off a side shoot from the plant, Gabriel prevails and continues nursing his treasure. One rogue member of the crew is one thing, but pirates are another, and the ship is besieged by pirates! Somehow, after surviving a daylong siege, the ship continues on before it’s almost sunk by a storm, which shatters the glass cabinet housing Gabriel’s precious coffee plant.

Gabriel Matthieu de Clieu caring for his coffee plant

After the pirate attack and the storm, fresh water supplies ran low and were rationed, forcing Gabriel to split his share of drinking water with the plant, which is now wilting as Martinique enters view.

On the island, Gabriel hides his crop among native plants and almost two years later, he shares his spoils with others. Within a short period of time, coffee plantations spread over the island and even over the the island of St. Dominique and Guadeloupe. With all of these prosperous plantations and after a few bountiful harvests, King Louis XIV forgives Gabriel for his treachery and makes him governor of the Antilles.

Gabriel’s gambit would seed the trees of the Caribbean, South American, and Central America. That’s quite the haul from just one small seedling, stolen with a snip.

With the wealth from coffee boosting the economies in the surrounding areas, Brazil decides that it too should have a future in the business of coffee. So under the veil of a peacekeeping mission, the Brazilian government sends Colonel Francisco de Melo Palheta to settle a disputed border between French Guiana and Dutch Guiana.

Despite the colonel’s success in brokering a peace, the French governor refuses his request for coffee seedlings. But the colonel was not to be deterred. While the governor heavily guarded the coffee plantations, he did not equally guard his beautiful wife. During a state dinner, the seduction began, and the colonel did indeed capture the heart of the governor’s wife. While that night they just danced, there were a few other, more intimate meetings, to say the least.

When at last Colonel Francisco departed for Brazil, the governor’s wife presented him as a token of her affections a bouquet of flowers secretly concealing a few coffee seedlings. Upon his return to Brazil, the colonel planted the seedlings on plantations in massive tracts of cleared rainforest. The resulting crop would later become an empire of coffee.

Jamaican Blue Mountains

Jamaica then jumps on the coffee bandwagon, where plantations in the Blue Mountain range are so bountiful that Jamaican Blue Mountain coffee quickly becomes traded throughout the world.

Soon, the Dutch and French trading of coffee is so strong that the British East India Trading Company gives up on its coffee trade and in short time tea becomes England’s drink of choice. Despite this shift, coffee houses still exists in England, though coffee’s popularity isn’t what it was in the heyday of the penny universities.

Meanwhile the strength and worldwide trading reach of the Dutch brings coffee to Japan, although it remained a curiosity among the Japanese until the strict trade restrictions were lifted in the middle of the next century.

And then, America hits England where it hurts, having a meeting at the Green Dragon coffee house in Boston, where the Boston Tea Party is planned and then carried out. As a result, the colonists start drinking coffee as a sign of patriotism.

While England had its stocks and commodities, newly independent America has Merchant’s Coffee House on Wall Street in New York, which will become the New York Stock Exchange, in an eerily similar echo of the Johnathan’s Coffee House becoming the London Stock Exchange.

1800s

Coffee is introduced to Hawaii, and after eight years of failure, the crops finally take hold, and Kona coffee is soon to come to a coffee house near you.

The 1800s are full of coffee-related innovation. In Paris in 1818, the first coffee percolator is invented by a Parisian metalsmith named Laruens. Four years later, the world’s first espresso machine follows, also developed in France. In New York, Jabez Burns patents the original Burns coffee roaster in 1864.

Meanwhile, James H. Nason patents the first coffee percolator in the U.S. Whether he came up with it originally or stole it from the French somehow, the bottom line is that the technology had come to America.

Arbuckle’s Ariosa

As for coffee itself, “Arbuckles’ Ariosa” becomes the first mass-produced coffee in 1871, taking the country by storm and leading founder John Arbuckle to export the coffee around the world.

Earlier in the century, the corporate coffee empires start to take shape. James Folger founds the J.A. Folger Coffee Company, believing that serving those looking for gold and getting their money is easier than actually going out and looking for the gold itself. This is the origin of America’s West Coast Coffee.

Then in 1886, coffee with a slogan (eventually) arrives. Joel Cheek names his new coffee blend “Maxwell House” after the hotel that served it in Nashville, Tennessee. Teddy Roosevelt’s 1907 comment “good to the last drop” launched the slogan that is still used to this day. It was also the first blended coffee in America.

There are two different philosophies when it comes to blended coffee. The first that commercial blenders cut high quality with low quality to keep the taste at a fairly high level while cutting costs. The second theory is completely based upon improving the flavor, though the price may increase. While both have their place alongside single-origin coffee, all three varieties are widely available on the market for your pleasure.

Before the turn of the century, coffee arrives in Tonkin, Indo-China, though it doesn’t really take off. At the same time in Australia, coffee is gripping the nation.

1900s

Local coffee roasters, shops, and mills are feeling the heat, losing market share and closing up all around America because of the Hill Brothers, who package their roasted coffee beans in vacuum tins, resulting in fresher beans at home. Also around this time Satori Kato invents a soluble blend of coffee, and instant coffee is now available. Meanwhile the Germans, fond of their afternoon coffee, start describing women who gather to gossip over coffee as a “Kaffee Klatsch,” to which “Coffee Talk” is the heir to the throne.

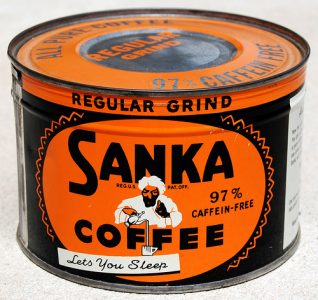

Soon coffee technology is moving at a much faster pace, as the first commercial espresso machine is invented. Also, Karl Wimmer and Ludwig Roselius accidentally discover decaf coffee, although their end result is salty. It wasn’t until the Swiss came up with a process that they would later brand “Sanka” that decaf became the decaf it is today.

Soon coffee technology is moving at a much faster pace, as the first commercial espresso machine is invented. Also, Karl Wimmer and Ludwig Roselius accidentally discover decaf coffee, although their end result is salty. It wasn’t until the Swiss came up with a process that they would later brand “Sanka” that decaf became the decaf it is today.

Instant coffee gets a move on with the creation of the first mass-produced instant coffee marketed as Red-E Coffee. Next up, the coffee filter as we know it is created by German housewife Melitta Bentz.

In 1920, the U.S. Congress enacts prohibition, and while speakeasies are on the rise, coffee sales go through the roof. More great news for the beverage hits in 1926 when the Science Newsletter declares coffee “beneficial.”

Now Brazilians have an issue with too much coffee and need something to do with their massive surplus. They enlist the help of Nestle to find a way to capitalize on their crop, and after years of experimentation, they find their answer with the help of Max Morgenthaler: “Waste not, want not.” Freeze-dried coffee is here to stay!

By 1940, the United States is importing 70 percent of the world’s coffee. Apparently the drink is here to stay, even after the end of prohibition.

Not to be overlooked, cappuccino is born by Achille Gaggia in Italy, 1946.

Then in the 1950s in coffee houses in America and England, the Beat Movement takes over with jazz and poetry and beatniks sitting around philosophizing. This isn’t much of a stretch from the “penny universities” of old England and the original coffee houses in Arabia. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

The Original Dunkin Donuts

Meanwhile in Quincy, Massachusetts, Dunkin’ Donuts is founded by William Rosenberg in 1950. But is there a feud in the family? Harry Winokur worked with the brother-in-law of Dunkin’s Donuts founder Rosenberg. After he broke his partnership with Rosenberg, he created Mister Donut in 1955, and the franchises were two of the largest in the country by the 1990s when Dunkin’ Donuts acquired Mister Donut, ending the rivalry.

Coffee marketing gets a face in 1958 as the National Federation of Coffee Growers of Colombia introduce the world to the fictional Juan Valdez. But that doesn’t mean coffee isn’t getting political… On trade agreements, President John F. Kennedy says in 1962, “We are attempting to get an agreement on coffee because if we don’t get an agreement on coffee we’re going to find an increasingly dangerous situation in the coffee producing countries, and one which would threaten the security of the entire hemisphere.” Later that year, an International Coffee Agreement is passed through the United Nations.

The Agreement sought to “create trading partnerships that are based on dialogue, transparency and respect, that seeks greater equity in international trade. These partnerships contribute to sustainable development by offering better trading conditions to coffee bean farmers.” And it did while it was renegotiated in 1968, 1976, and 1983, impacting the fairness of retailers, importers, and exporters.

In short order, the other two of the current big three coffee chains in North America will be founded to join Dunkin’ Donuts. In Hamilton, Ontario, Canadian hockey player Tim Horton and Jim Charade found Tim Hortons in 1964. Initially a hamburger joint, it expands into over 4,000 locations. Seven years later in Seattle, Washington, the first Starbucks opens.

Original Mr. Coffee

In homes, Mr. Coffee is born in 1972 as the world’s first automatic drip home coffee maker thanks to Vincent Marotta of Cleveland, Ohio, ushering in a new era in homebrewed coffee.

In 1989 coffee prices drop radically as the participating nations in the International Coffee Agreement fail to reach a new agreement. Coffee is now more accessible and cheaper, but that doesn’t mean what Kennedy said in 1962 isn’t still valid. After all, coffee is a commodity, like oil. In 1992, a new agreement is reached and has been successfully renegotiated since.

Conclusion

I don’t think it’s too big a stretch to say that coffee was bound to be globally popular. Just as civilization grew from Mesopotamia and the fertile crescent, coffee too originated from the same geographical area.

Today coffee is known and being consumed the world over. Amazing how all of this happened from one little bean.