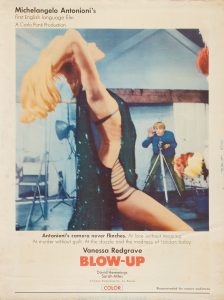

1966’s Blow-Up is the pinnacle of avant-garde filmmaking in the pop art, swinging sixties directed by Michelangelo Antonioni.

Not only is it the story of a mod London photographer who finds something beautiful and sinister in the photographs he has taken of a mysterious beauty in the park, but it is the perspective of the swinging sixties through that photographer’s eyes, as well.

Thomas, the photographer, played by David Hemmings, is a modernist and as much a part of the Mod subculture that made London the center of music and fashion, drugs and free love, that was the swinging sixties.

Thomas doesn’t get much sleep, but that leaves more time to take photographs and experience the scene as I have described. After taking some pictures of a nameless beauty and a man, he finds more in the frame than he bargained for. As he magnifies the picture, the story of exactly what he captured both becomes more clear and more distorted.

When Jane, the nameless beauty, asks for the pictures back and says that he “can’t photograph people like that,” Thomas simply replies, “Who says I can’t? I’m only doing my job. Some people are bullfighters, some people are politicians. I’m a photographer.”

Antonioni has said, “It’s the story of a day in the life of a photographer and what he experiences during this day. I say experience because it’s through his photographs that he discovers what he hadn’t seen. That’s why I speak of experience and that’s why it’s important, important enough to put him into a state of crisis at the end of the film.”

1966 Blow-Up Poster

And that’s the rub, that’s all you really need to know of the plot because the real talking point (after the plot) is the setting, both of the film and within the film.

The fashion, the art, the sex, and the music make this one of the best snapshots of swinging London that I have seen. Now, I may have been born after that time period, but of the things I’ve watched and read, most notably both of Michael Caine’s autobiographies, there’s a certain allure and fixation that the world had on London during the sixties. Caine paints quite the picture himself, having come to stardom during that time, he had his fill of the period.

And in discovering Blow-Up thanks to a mention in Joe Perry’s autobiography (Thanks, Joe), I now have a better visual representation of the era.

The fashion is very much a part of the story and the time. Thomas is stylish, collared shirt with a few buttons open, a nice jacket at times and always with disheveled hair. In fairness, he looks and dresses better in this film than I do on even my best days. But it’s the women he’s around and that he takes pictures of that are emblematic of the time. Lots of bright colors, patterns, and of course, skin. It’s not blatant, but a dress with no sides, or some of the more out of the ordinary impractical designs that are still gracing the runways of Paris and Milan, can be traced back to this time and this place.

The bright colors are also part of the bright contrast of the sets. The studio where Thomas works has exposed wooden beams contrasting with bright white walls, and beyond that everywhere there is art, sculptures, trinkets, and bric-a-brac in various shapes, sizes, and colors to fill up the screen when there’s not much else going on when the camera lingers about the set.

Color was a very important part of the film to director Antonioni, “I used color in an apparently realistic way. I accentuated reality more, because I had to create a portrait of this reality.” And he succeeded in not only making color a part of the film, but in giving us one of the more visually realistic visuals of the Swingin’ Sixties.

The music is also of grand import to the setting. The Yardbirds make an appearance in the film as themselves, ripping off Train Kept A-Rollin (a song which they covered and popularized) with new lyrics as Stroll On, with a very different intro which might as well be a separate song called Sweet Music.

But that’s not the only song to make the soundtrack. The Lovin’ Spoonful’s “Did You Ever Have to Make Up Your Mind?” also appears with the score, which was the first film score composed by the legendary Herbie Hancock.

But that’s not the only song to make the soundtrack. The Lovin’ Spoonful’s “Did You Ever Have to Make Up Your Mind?” also appears with the score, which was the first film score composed by the legendary Herbie Hancock.

Back to the film itself, it may be a mystery in a period piece set and shot in the period, but it is as much about Thomas, the photographer, as an artist as it is about anything else. Michelangelo Antonioni shot, wrote and directed this to as close to perfection as could be mortally accomplished.

It’s arguably been called one of the best English films, which is interesting because it came from the vision of an Italian. Perhaps, it is an outsider who can best see the situation. Observations of the stranger in the strange land, may perhaps be more perceptive than those who inhabit the strange land, to begin with.

So, go see it. Blow-Up is one of those captivating older films that inspired those that came before me, and is still inspiring to this day. Go see it for the mystery, but stay for one of the most realistic representations of the swingin’ sixties in London ever put on celluloid.

Read the Secret File of technical information and quotes from Blow-Up.