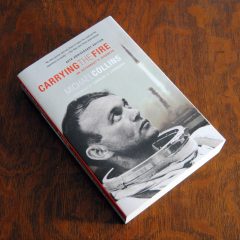

There is something uniquely wonderful about the autobiography of Michael Collins, Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut’s Journeys, and it is indeed the author Michael Collins.

Collins writes of his journeys into the astronaut corps and of his flights on Gemini 10 and Apollo 11 with such descriptive simplicity, that the book is both hard to put down and hard to continue without taking a moment to think about the story he has just told.

In fact, the beginning Foreward written by aviation pioneer Charles A. Lindbergh says as much; “Perceptive, clear, and comprehensive, targeted on life’s first expedition to the moon’s surface, this book combines a contemplative mind and poet’s eye with the essentially practical approach of a participating astronaut. Here is a fascinating autobiographical account of one of civilization’s greatest adventures. It will be read and reread as long as records last.” And I couldn’t agree more.

Collins has simplified the math, he has dumbed down the theoretical and yet he isn’t actually talking down (or in this case writing down) to the reader at all. He is simply explaining, in plain English, the story of his life and of course his flights in space. Whether it be his spacewalk during Gemini 10 or his part in the historic Apollo 11 success.

Apollo 11 Astronaut Michael Collins

And in doing this so succinctly, he has fulfilled that which he has set out to do. “I bore easily, and I have written for people who bore easily. If I have done my job properly, the reader will be able to pick the book up at any point and find something interesting going on, because that is the way Houston and the other space places were in the sixties. There was never a dull day, and there should be no boring pages.”

There are examples of this simplicity in complex storytelling throughout the book, but I have selected a few examples:

“In a test pilot’s world, boring is good, because it means that you haven’t been surprised, that your planning has been precise and your expectations matched. Conversely, excitement means surprise, and that generally is bad.”

“I remember last December, during the flight of Apollo 8, my five-year-old son had one, and only one, specific question: who was driving? Was it his friend Mr. Borman? One night when it was quiet in Mission Control I relayed this concern of his to the spacecraft, and Bill Anders promptly replied that no, not Borman, but Isaac Newton was driving. A truer or more concise description of flying between earth and moon is not possible. The sun is pulling us, the earth is pulling us, the moon is pulling us, just as Newton predicted they would.”

“TEI. Transearth injection. NASA jargon has an uncanny knack of disguising the meaning of even the most obvious things. This is the get-us-home burn, the save-our-ass burn, and they call it TEI.”

Astronaut Michael Collins

“Jesus, they could fly this command module one hundred times, and on the one hundred and first, some engineer somewhere would come up with a procedure that he was convinced should replace all its predecessors.”

Although there are many other such examples, there is something else unique about Collins, two things actually.

The first rears its head in training. As Collins explains, “there were actually eleven points along the Apollo 11 flight path that merited special attention, and I tried to distribute my training time in such a way that I was familiar enough with them to perform my routine chores smoothly and to understand the equipment design and its use well enough to cope with failures that might reasonably be expected to occur.“

Those eleven were Launch, TLI (Translunar injection), T&D (Transposition and docking), LOI (Lunar orbit insertion), DOI/PDI (Descent orbit injection and powered descent initiation), Landing, EVA, Lift-off, Rendezvous, TEI (Transearth injection), and Entry. And the last one, although it is a vital part of every space flight had an extra heavy weight to it. While Collins simply describes each of the first 10 points, it is in the subtext of his short description of the 11th and final point “Entry” where we really understand the pressure he was under.

“Entry. Diving into the earth’s atmosphere at precisely the right angle was required for a successful splash, not to mention the flawless on-time performance of the parachute system and related claptrap. I could fly the entry phase, because, of course, I had to learn how to do it all in case I came back from the moon without Neil and Buzz.”

Apollo 11 Astronauts Aldrin, Collins, and Armstrong

I’ll repeat that “I had to learn how to do it all in case I came back from the moon without Neil and Buzz.” That’s right. Michael Collins, Command Module Pilot for Apollo 11, might have had to leave his fellow astronauts, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the surface of the Moon if the LM couldn’t take off. That in itself is an extremely heavy burden to bear. He doesn’t delve too deeply into this contingency, but he mentions it with enough frequency that you know he spent quite some time not thinking about it.

Yet, for all the feats of Apollo 11, none was more personal to Mike as his solitude, which he describes so well, I’ll just share it with you here:

“I know from pre-flight press questions that I will be described as a lonely man (“Not since Adam has any man experienced such loneliness”), and I guess that the TV commentators must be reveling in my solitude and deriving all sorts of phony philosophy from it, but I hope not. Far from feeling lonely or abandoned, I feel very much a part of what is taking place on the lunar surface. I know I would be a liar or a fool if I said that I have the best of the three Apollo 11 seats, but I can say with truth and equanimity that I am perfectly satisfied with the one I have. This venture has been structured for three men, and I consider my third to be as necessary as either of the other two.”

“I don’t mean to deny a feeling of solitude. It is there, reinforced by the fact that radio contact with earth abruptly cuts off at the instant I disappear behind the moon. I am alone now, truly alone, and absolutely isolated from any known life. I am it. If a count were taken, the score would be three billion plus two over on the other side of the moon, and one plus God only knows what on this side. I feel this powerfully—not as fear or loneliness—but as awareness, anticipation, satisfaction, confidence, almost exultation. I like the feeling. Outside my window, I can see stars—and that is all.”

Collins photo of the Eagle from Columbia

We know the heavy burden of potentially coming back alone did not come to pass, yet there’s still another burden that weighed pretty heavily on all three men: Neil, Buzz, and Mike.

As Collins writes, “Unlike Gemini 10, which ended the instant we hit the water, this flight will never truly be over in my lifetime (such is the distinct impression I get from the newspapers), but I may wish that it were.”

And the two follow up statements are “Being an astronaut is a tough act to follow, as all three of us have discovered,” as well as, “It is the curse of flying in space, this business of answering the same question one million times. There should be a statute of limitations on it.”

Reading this book is just like sitting down for a cup of coffee with the man who spent a good portion of his life, risking it all, to attempt what became one of the 20th century’s greatest achievements.

But the takeaway for me is that while many books and documentaries have noted the strain on relationships for those during the Moonshot years at NASA, Collins is still happily married to his wife. And the most heartfelt portion of this book, belongs to her, Pat Collins and the poem she wrote for Michael before he took off for the moon. And there could be no better way to honor her life (she passed away in 2014) than to reprint those loving words here.

But before I do, go get Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut’s Journeys and enjoy all that it has to offer.

Michael and Patricia Collins

To a Husband Who Must Seek the Stars

In your eyes the first glad token

As when first our love we proved,

So you mind to mine has spoken

Just as if your lips had moved.

You are saying—yes, I know—

That the lure of space beguiles.

You are pleading—”Let me go,”

Not unwilling, but with smiles.

Can you love me, and still choose

Whispers that I cannot hear?

Late to love, how can I bear to lose

Content for some inconstant sphere?

Tell me how you see my role—

To stay, to wait, yet yearn to go.

Where is the comfort for my soul?

You, my love, have helped me know:

I’ll be unafraid, undaunted.

Yes, of course! I need not face

Any peril; or be haunted

By the hazards you embrace.

I could have sought by wit or wile

Your bright dream to dim. And yet

If I’d swayed you with a smile

My reward would be regret.

So, for once, you shall not hear

Of the tears, unbidden, welling;

Or the nighttime stabs of fear.

These, this time, are not for telling.

Take my silence, though intended;

Fill it with the joy you feel.

Take my courage, now pretended—

You, my love, will make it real.