In Love and Anger: A View of the Sixties by Andrew Sinclair is not just a memoir and it is not just a history book, but a uniquely written and brilliantly choreographed combination of the two. It could very well be one of the few de facto personal memoirs that also combines historical facts and lessons either through personal experience or through the much-touted shared experiences of the era that brought about rebellion, social change, challenge and discourse, art, music, love, and anger.

Calling upon not only his experiences but his knowledge of the words spoken and written in the moment, and in an afterthought of the sixties, by some well-known and forgotten professors, writers, leaders, and artists, this book is a comprehensive dive into the many movements and events that made up one of the more volatile eras of the twentieth century.

And to me, it is Sinclair’s inclusion of all of those other words that are not his, combined with his experience of having been alive to see the things those other names (of which there are too many to list) either wrote or spoke, that really combine to put any reader who picks up this book right there in the place and the time with all of the context necessary to understand what went right and ultimately what went wrong as well.

What is most telling, however, is that this book, written more than two decades after the events described within, gives us some prime insights into the issues we once again face today, as well as, the coming of age trials and tribulations that every next generation goes through as it battles with its own youth culture versus the establishment.

Author Andrew Sinclair

“For in youth we are always the heirs of an established past which allowed us to become the predators of the present.” Of that predatory youthfulness “We hardly ever know the effect of what we do. If we did, we might be circumspect” and “It is wonderful how we chance our arm when we are too young to reckon the consequences.”

But that youthful rebellion has more sides than right and wrong, “For he thought that the pursuit of freedom mattered, not its conquest. Once it was achieved, all discipline was discarded, and decadence resulted without any visible future.” And while that holds true, what may hold more weight is that from youth and youthful rebellion “What we had gained, we now might wish to keep. I already knew, or thought I knew, that it was the fate of all revolutions as well as generations to conserve the fruits of the revolution and to become the keepers of the old faith, not the torchbearers of the new…”

And that establishment that the youth rebel against is often political power, which comes in the form of men in power. “This was my lesson in the power of democracy. Its heroes and presidents, Truman and Kennedy, could still hear the cries of the people and knew the political machines well enough to make reform work. It was direct and effective, and when it grew corrupt, it could be mended. The vote was what mattered, and demographic and economic changes meant that no party boss could manage his ward for ever.”

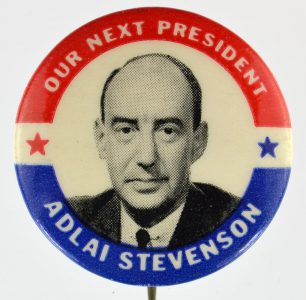

But Sinclair also mentions “One of the best presidents that America had, Stevenson would rather have wit than the White House.” as well as the fact that ‘a principal social function of science is to act as scapegoat for the blunders and malfunctions of its political masters.’

Stevenson for President

Of race, one of the things we still deal with all too regularly in regards to discrimination, Sinclair had a question then as we all still do now, “What to do with those who want to perpetuate and exaggerate the divisions of race, who wish to falsify history in order to prove that racism always was and will be paramount, who interpret their every paranoia as a just view, who think that each demand is a fair recompense for the past suffering of their people?”

However troubling some of those similarities may be to today’s current political climate, Sinclair does bestow upon the reader some genuinely good insight in regards to general wisdom with:

- “‘the test of a first rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.”

- ‘Nothing you do outside is important unless you’re centred within.’

- ‘Purposeless play is creative. The most inventive scientists and researchers play. Many new inventions started out as play. Artists play.’ The reason why was that play was an affirmation of life. It was not an attempt to bring order out of chaos or to try and improve things, merely a way of awakening to life as it was, and letting it be.

- Power corrupts. Powerlessness corrupts absolutely.

- Those who live by conspiracy, alas, can only see the lives of others as conspiracies.

- Marx’s dictum that history repeated itself first in tragedy and then in farce seemed no longer true. Now history was repeating itself first in egocentricity and then in force.

But this book is about the Sixties and in hindsight and through some of his writings during the era, Sinclair comes to some pretty stark conclusions.

First, of hope in the Sixties, “It was a limited hope, but there was hope, to be shattered by three bullets fired in Dallas in conspiracy or madness.”

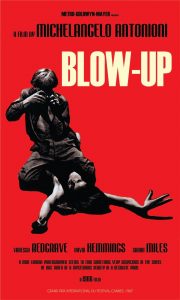

Blow-Up Movie Poster

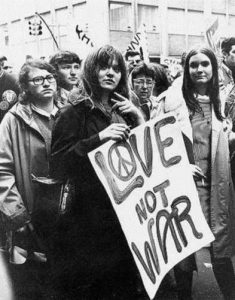

Second, that “The colourful clothes and long hair of the ‘sixties were emblems of tolerance and novelty, experimentation and delight.”

Thirdly, “It was also the sin and the virtue of the liberal ‘sixties, a blanket permission to do whatever you wanted. No limits were left, the markers were moved beyond the horizon towards Shangri-la.”

And if you want a concrete visual of the era, at least in London then you need to watch the film Blow-Up, which he states in looking back “would turn out to be the definitive statement of how young life in London appeared to be right then.”

But we all know that era came to an end. Whether it was “the solidarity and harmony of the underground were breaking up like the fragments of a grenade.” or “The failure of the urban rebellions of 1968 had heralded the failure of the alternative and counter-cultures” is still up for discussion.

What we do know is that of both of the “two methods were being advocated of unseating governments — by outrage and fun or by sabotage and gun” and neither regularly comes through on its promise of change when taken as slogans for action.

However, as a people on the planet earth, one thing that is hardly arguable is that “‘We are full of dreams, but they are dreams of a vanished past because nostalgia is the opium of the people.’”

The lessons from this book are written proof that while the environment changes and technology advances, we still continue on a path towards what seem to be universal cyclical problems. And to me a good portion of that is not necessarily our own faults, but that the advancement of technology will from time to time hide these issues that resurface in new environs making them appear to be wholly new problems when in fact they are just the remnants of the past still yet to be resolved.

The lessons from this book are written proof that while the environment changes and technology advances, we still continue on a path towards what seem to be universal cyclical problems. And to me a good portion of that is not necessarily our own faults, but that the advancement of technology will from time to time hide these issues that resurface in new environs making them appear to be wholly new problems when in fact they are just the remnants of the past still yet to be resolved.

This book was written by Sinclair but he did his homework too, he couldn’t have written it so thoroughly and completely without knowing that his story and his experiences alone were not enough to complete the picture.

Sinclair ends the book by stating what he set out to do at the start “I have tried to express this thinking by interweaving social history with my life in these years. Occasionally, and often unwillingly, we do find ourselves briefly a part of what has gone by.”

And in the end, he acknowledges that he alone was not the sole perspective or perpetrator of this narrative, which for a time changed the world… “What happened to each one of us individually may have affected some or many of us. In the little may lie the large.”

For anyone out there who is interested in the past, human nature, and the future, this book is a must-read. It may not be so readily available as War and Peace, but it is well worth your effort to hunt down a copy and crack open its pages. You won’t be disappointed that you did.

Read the Secret File of technical information and quotes from In Love and Anger by Andrew Sinclair.