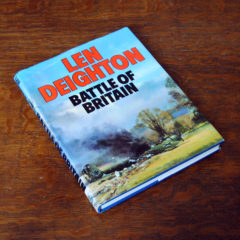

There is something remarkable about reading Battle of Britain by Len Deighton. First, it is hardly the first book about the Battle of Britain I’ve read, second, all the others, even if they were more broadly World War II based, were all written by him, and third, I still learned something new.

I’m not sure if he uncovered more information during his research for this book or was just more able to tell the story, but this book is not only direct in its retelling of history but it’s also a work of art.

Now, at the very beginning, Deighton himself writes, “This book is an attempt to look at the Battle within the context of history, separated from the high-powered propaganda from both sides much of which still distorts current beliefs about what actually happened.”

I’m not sure how much of his own writing he is including, but this feels different enough from Fighter and Blitzkrieg to almost verge on self-depreciation a bit.

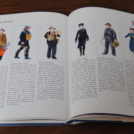

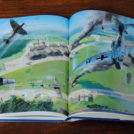

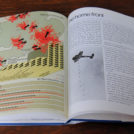

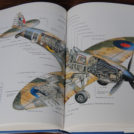

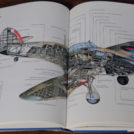

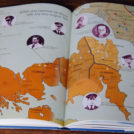

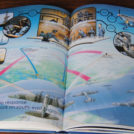

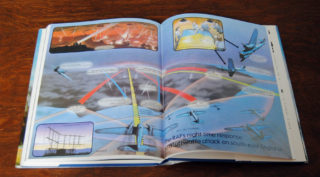

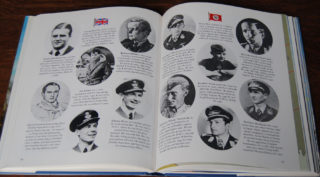

Deighton boils the essence of the battle down into three key points that are told through first-hand accounts, research, pictures of documents and propaganda, and beautiful illustrations.

- Germany and the Luftwaffe had air superiority in every way, except their poor tactics led to their own downfall

- Britain succeeded by not being drawn into every fight in the skies overhead

- After the Battle, Britain failed to learn from its own history lesson.

“On Saturday, 7 September, Goering stood on the cliffs at Cap Blanc Nez with Kesselring and Lörzer, watching the great German formations sweep overhead. ‘I myself have taken command of the Luftwaffe’s battle for Britain’, he announced to the German people on the radio. On that day, in response to Bomber Command’s attacks on Berlin, the first major air assault on London took place. Although the capital would now suffer months of punishment from the Luftwaffe, Goering had disastrously lost sight of strategic priorities. The diversion of forces against London was one of the greatest blunders of the battle.”

“On Saturday, 7 September, Goering stood on the cliffs at Cap Blanc Nez with Kesselring and Lörzer, watching the great German formations sweep overhead. ‘I myself have taken command of the Luftwaffe’s battle for Britain’, he announced to the German people on the radio. On that day, in response to Bomber Command’s attacks on Berlin, the first major air assault on London took place. Although the capital would now suffer months of punishment from the Luftwaffe, Goering had disastrously lost sight of strategic priorities. The diversion of forces against London was one of the greatest blunders of the battle.”

The Luftwaffe could have continued to pummel Britain’s industry, but the lure of London was too great. This also helped with British morale, as the lower classes thought it appalling that the London elite and parliament were spared the early bombing runs. And while the lower classes were unhappy to bear the brunt of the offensive, they still didn’t take too kindly to the bombing of the capital.

“It required great moral courage as well as strategic judgement for Dowding and Park to fight the Battle of Britain by their brilliant measured strokes. Their refusal to send fighters into the air to meet the great German Bf 109 sweeps over south-east England was a classic display of masterly inactivity. The other inspired move was to order the British fighters to concentrate on shooting down bombers. It did not conform to any of the romantic notions about chivalrous jousts between knights of the air, but it baffled and finally defeated the Luftwaffe.”

In hindsight, it makes perfect sense not to send up a response team to a fighter sweep that won’t inflict nearly the damage as a bomber wing, but to knowingly let the enemy fly unimpeded overhead, took a courage that lost Dowding and Park their jobs, despite the fact that that very move of nonaction was what won the war.

In hindsight, it makes perfect sense not to send up a response team to a fighter sweep that won’t inflict nearly the damage as a bomber wing, but to knowingly let the enemy fly unimpeded overhead, took a courage that lost Dowding and Park their jobs, despite the fact that that very move of nonaction was what won the war.

But what’s most baffling of all, “Perhaps the most astonishing feature of the Battle of Britain and the revelation of the British people’s ability to withstand bombing is that from 1940 onwards, the British Government set about investing huge resources in its own Bomber Command. Against all logic, it allowed the Royal Air Force to spend most of its resources and the lives of 56 000 aircrew attempting to break the will of the German people in just the way that Fighter Command and the British people had proved could not be done.”

Besides the artwork, Deighton’s inclusion of excerpts from Mass Observation is by far the most colourful part of this book. In fact, I find the very concept of Mass Observation (MO) astounding. “By far the most interesting evidence of popular attitudes is contained in the arches of Mass Observation, an organization set up just before the war by Dr. Tom Harrisson, which encouraged hundreds of ordinary people to keep diaries of their daily lives and experiences and report to MO month by month. Today, the MO reports form the most varied – and uncensored – contemporary testimony about British morale in the war.”

Two such examples follow below, one from a civilian girl, one from a pilot.

Two such examples follow below, one from a civilian girl, one from a pilot.

It was a beautiful summer night, so warm it was incredible, and made more beautiful than ever by the red glow from the East, where the docks were burning. We stood and stared for a minute, and I tried to fix the scene in my mind, because one day this will be history, and I shall be one of those who actually saw it. I wasn’t frightened any more, it was amazing; maybe it’s because of being out in the open, you feel more in control when you can see what’s happening. The searchlights were beautiful, it’s like watching the end of the world as they swoop from one end of the sky to the other. . . .

A London girl writing to Mass Observation 9 September 1940

…Two further pilots have come to us straight from a Lysander squadron with no experience whatsoever on fighter aircraft. Apparently demand has now outstripped supply and there are no trained pilots available in the Training Units, which means that we will just have to train them ourselves. However it remains to be seen whether we can spare the hours, as we are already short of aircraft for our own operational needs. It seems a funny way to run a war. . .

Sandy Johnstone, 602 Squadron, 3 Sept

There’s a lot to be said for World War 2, but the Battle of Britain was its turning point and this book is a brilliant way to learn about it.

Read the Secret File of technical information and quotes from Battle of Britain by Len Deighton.