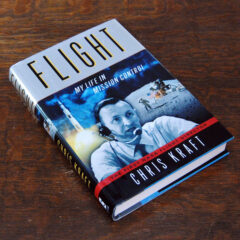

When you read as much on the subject of early NASA even back to the Space Task Group, predecessor to NASA, there are a few names that always come up, and one of them is Chris Kraft. He was basically the father of what would become Mission Control as we know it today, and in his autobiography Flight: My Life in Mission Control, the first NASA Flight Director, known simply as Flight, holds no punches.

While Gene Kranz may be more well known as a member of Mission Control because of the success of Apollo 13 at the box office, and having been played by Ed Harris didn’t hurt, for those who don’t know Kraft, he literally wrote the book on Mission Control, and he picked Kranz to be a Flight Controller.

And when I mean wrote the book, I mean it. When putting together one of the original Mercury RFP (Request for Proposal), Chuck Mathews who was in charge of the operations section said “‘Our part’s simple,’ he told us. ‘Chris, you come up with a basic mission plan. You know, the bottom-line stuff on how we fly a man from a launch pad into space and back again. It would be good if you kept him alive.’”

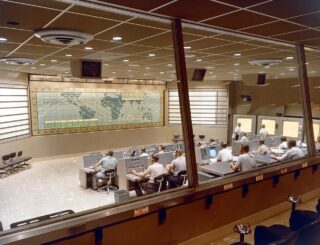

And this book details the origin of Mission Control as we now know it and as you can see on quite a few documentaries of late as the camera has turned to shine a little more light on the other end of the astronaut headset conversations.

Kraft does a superb job of clearly illustrating the concept of organization. Aside from creating the actual control systems and processes and the flight planning for the missions, he is the man in the chair until he’s management. But even once he’s Management he wants to be in the chair. But you have to trust your guys and he did, though it did take some self-control. And while he only mentions a few other names in passing, all of the men in the chairs during Mercury and Gemini needed to pick the right people as the program rolled into Apollo

But it wasn’t all planned. It is kind of amazing that while some of the preparation for Apollo was planned to happen in Gemini, like rendezvous, space-walk, and long duration flight, there were setbacks and failures that allowed for preparations that weren’t planned for such as the revamping of Gemini VI and VII to Gemini 7/6, where the crew at MCC would have to monitor two separate vehicles in space simultaneously. Something that was good they did before Apollo.

While Kraft does celebrate the highs of space flight and the space race, this book is perhaps the most “how the sausage gets made” of all of the NASA biographies I’ve read so far. Its politics and the egos are, to my eye, as honest as I’ve ever seen. Also, Kraft, like his one-time first lieutenant Kranz doesn’t name-drop astronauts. They were the pilots of the ships, but this book isn’t about gritty details of the men who flew, it’s about the design and development of the machines and systems that took man into space and on to the moon. It’s amazing because of the politics and ego that we even got there…

Kraft doesn’t mince words. “I look back now and shake my head. Today the government may spend a year thinking about, then preparing, a Request for Proposal. There’s a cover-your-ass mentality that has to dot every i, cross every t, and get some lawyer’s initial on every page. It may be six months before contractors have to respond. Then the evaluations stretch toward infinity. By the time a major contract is awarded, the original idea may be several years old, technology has passed it by, politics has intruded and changed the mission or the rules, and the inevitable redesigns consume more years. The International Space Station is a perfect example of a bad plan followed by more than a decade of middle modifications in both design and mission. If we’d had a 2001 bureaucrat running the Space Task Group in the late fifties, the Russians would have clobbered us in space, and the last forty years of the twentieth century may have played out far differently than they did.”

Mission Control during Project Mercury

And it’s hard to argue with him, so I won’t. Additionally, one of the things most blatantly obvious is that the men of Apollo, those who flew and those who controlled and assisted with the engineering were not thrilled with the short-sighted nature of the shuttle. They were not sated with the direction that NASA headed once Kennedy’s goal was achieved and in honesty, all their books end not triumphantly but with a kind of dejection for what became of a once great collection of public and private industries reaching toward a common goal.

Is it too late to turn it around? Perhaps, but perhaps not. I don’t claim to have an answer, but I know that Kraft, alongside Kranz and Gilruth, Armstrong, Aldrin, Lovell, Shepherd, Glenn, they would all want us to do more than we are. Because right now, we’re not doing much of anything. And, if they had had their way a manned mission to Mars would have already been tried, years ago.

We no longer look to the heavens in that way. SpaceX and NASA may finally be going back to the moon, and we’re again talking about Mars, but is the romance still there?

Perhaps Kraft and his cohorts were the peak. It would be sad if they were, and they would be sad if they were. They were all proud of what they accomplished, but none of them saw the Moon as the end… To them it was just the beginning, a stepping stone. And perhaps, I am biased, but I agree.

In the meantime, add Chris Kraft’s autobiography Flight: My Life in Mission Control to your reading list.