As one of the younger persons in the generation that Douglas Coupland arguably named Generation X, it is no surprise that he can write so methodically and philosophically about tragedy and grief.

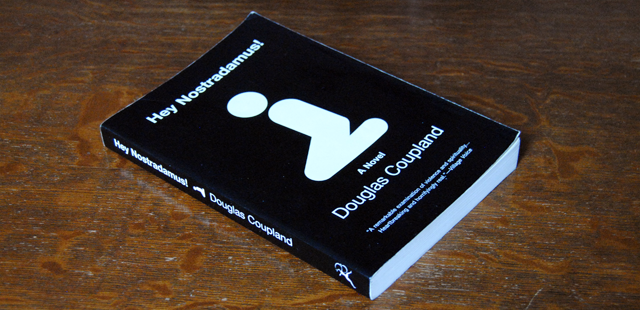

Specifically, in Hey Nostradamus, he encapsulates the tragedy and grief surrounding a high school shooting in North America. There is just something about Coupland’s ability to carve right into the collective psyche of the generation that I inhabit. I recognize the underlying truth in his fiction, yet I don’t comprehend how he does it so well.

The book is set up in four chapters, each told from the perspective of a unique character. Those four voices, while individual in their own way, are wildly interconnected because of one singular event. There is something in that link that makes this book about tragedy, grief, and our response to it that much more vibrant and varied.

I’m going to use the back cover to provide some non-spoiler context. As it states, this book is “overrun with paranoia, teenage angst and religious zeal in the ensuing massacre’s wake.” What makes the bulk of the book and really drives some poignancy to recovery or lack thereof, however, is that for our four main characters “still reeling from that horrific day, life remains perpetually derailed.”

Author Douglas Coupland

“Four dramatically different characters tell their stories in their own words: Cheryl, who calmly narrates her own death; Jason, the boy no one knew was her husband, still marooned ten years later by his loss; Heather, the woman trying to love the shattered Jason; and Jason’s father Reg, whose rigid religiosity has separated him from nearly everyone he loves.”

If you want to completely philosophically dissect the book, you can, but I chose to look at it sociologically. Aside from Cheryl depicting the events of the massacre, each of the characters deals with tragedy and failure beyond that one singular event. Some circumstances are direct ripples caused by it, while others are in spite of the event itself.

There are lessons in this book that, while stated by the characters, are larger than them. We obtain them not only from the dialog they share with others but because of the unique place we occupy in their heads in each respective section of the book. Despite the gender, age, relationship, economic, and other diversities of the four characters, they are all, at points, relatable to readers who may overlap said storytellers in age, gender, or similar situations.

We all deal with loss, love, failure, hope, and faith, and we often do so as a result of the tragedies we must overcome. What you take away from this book may be very different from what I did. But what I did take away were the following quotes: the first five feel like universal truths (at least to me) and the last feels very much like a universal question.

- We’re the sum of our decisions.

- A bland smile is like a green light at an intersection — it feels good when you get one, but you forget it the moment you’re past it.

- …you spend a much larger part of your life being old, not young. Rules change along the way. The first things to go are those things you thought were eternal.

- …every human being you see in the course of a day has a problem that’s sucking up at least 70 percent of his or her radar.

- Most people might view Jason as a failure, and that’s just fine. Failure is authentic, and because it’s authentic, it’s real and genuine, and because of that, it’s a pure state of being.

- “Why is exposure to pain always supposed to make us better people?”

What is most interesting about these six thoughts from this book is that, as a fan of Coupland and therefore for better or worse, these could come from any character in any of his previous novels I have read.

What is most interesting about these six thoughts from this book is that, as a fan of Coupland and therefore for better or worse, these could come from any character in any of his previous novels I have read.

That is why I love Coupland’s work. It’s why I continue to read his stuff, fiction and nonfiction. It feels like he and I are having a conversation. He might be telling the story, but it feels like I could jump in at any moment. The way he writes these stories and characters makes it feel like they’d let you jump into the conversation, or their personal thought bubble, even though you might not want to interrupt their thought process.

I’ve not read any other authors where that feels possible. Perhaps it is just me, and I’m okay with that too, but read Coupland’s fiction for yourself, even if it’s just one or two of them, and let me know what you think.