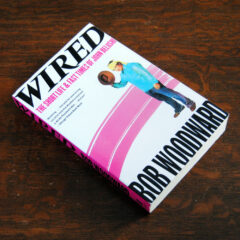

Wired: The Short Life & Fast Times of John Belushi is a very intriguing and thought provoking detailed trip of Belushi’s life by renowned journalist Bob Woodward.

The book wants to be a straight-forward, facts forward retelling of Belushi’s life with the words and experiences of those who were around him at the time. On the surface, that might be exactly what it is, but it is so much more than that.

It speaks to something larger about our current entertainment setup. It speaks to artists and their relationship with the monetary institutions that fund their art. It speaks to success and how not everyone has the willpower to contain or remain themselves once they are over the threshold of celebrity.

It does all of this while documenting one of the brightest shooting stars of comedy from the 1970s.

Unfortunately, recollections and inferences are all we have left of Belushi that wasn’t put on film. I get the feeling that not only was Hollywood not a great fit for him but that celebrity was not a great fit for him either. Neither of these are hot takes, nor do they go out on a limb. What’s troubling for me as a reader of this book in the 2020s, however, especially for a book that was written four decades ago, is that nothing seems to have changed.

Am I a fan of John Belushi? I am, and I don’t know who couldn’t be. I read through his experiences after Saturday Night Live, though, and I think that it’s not very different from the Hollywood and big business of television and movies that I read about today.

I’m not an idiot. I understand that it does take money to create art, especially in a world were greed is still apparently good. Coming off of the recent SAG-AFTRA actors and WAG writers strikes, I can’t help but think that the studio system that didn’t think to check up on Belushi’s mental health, drugs aside, is the same system that is still in place today.

I’m not an idiot. I understand that it does take money to create art, especially in a world were greed is still apparently good. Coming off of the recent SAG-AFTRA actors and WAG writers strikes, I can’t help but think that the studio system that didn’t think to check up on Belushi’s mental health, drugs aside, is the same system that is still in place today.

Reading this book, it’s more a wonder that we haven’t lost more shooting stars like Belushi. It’s almost more curious how Bill Murray, Dan Aykroyd, and Chevy Chase among others survived their time in the muck to emerge on the other side.

Perhaps it was all drugs and self-sabotage and getting out in time, but this book points a very direct finger at the pressure that capitalism puts on the moneymaking success of making art, and less on the art itself. It’s not the main focus of the book. In fact, it takes a back seat to the drugs. The chaos of the first part of the book is only topped by the chronicles of the chaotic last week of Belushi’s life, but that doesn’t make the blame any less on the greed of the industry.

This book has me rethinking the fault of drugs in all of those other shooting star deaths, with Hendrix and Joplin as quick examples from the same era. The music industry is no different than the film or television industry. “Hey that’s great art, let’s make some money. Cool, now let’s do it again.”

Sure, there are personalities that are more susceptible to drugs and alcohol, but much of that artist dependence is often a way to deal with the pressure.

There’s an inference in the early part of this book that makes so much sense to me. Woodward is describing the early drug use of Belushi and his friends as, “Drugs were the only way to get away. There wasn’t the time or the money for real vacations. Drugs were a necessary recreation; $5 or $10 was well spent for some pot or several ‘tabs’ of the latest mind-bender.”

There’s an inference in the early part of this book that makes so much sense to me. Woodward is describing the early drug use of Belushi and his friends as, “Drugs were the only way to get away. There wasn’t the time or the money for real vacations. Drugs were a necessary recreation; $5 or $10 was well spent for some pot or several ‘tabs’ of the latest mind-bender.”

I know that this book has taken some flak about Woodward’s research and about some of the facts within it, but it does paint a pretty compelling picture of Belushi. It’s one that, even with a grain of salt, is worth perusing. But I must warn potential readers that it is a dense read and, of course, it doesn’t really have a happy ending.

Still, it has its moments and on the whole is thought-provoking. Perhaps we will eventually see a change in the system that definitely in some way contributed to Belushi’s death. Then again, perhaps we won’t. I stand with the artists. I stand with Belushi.