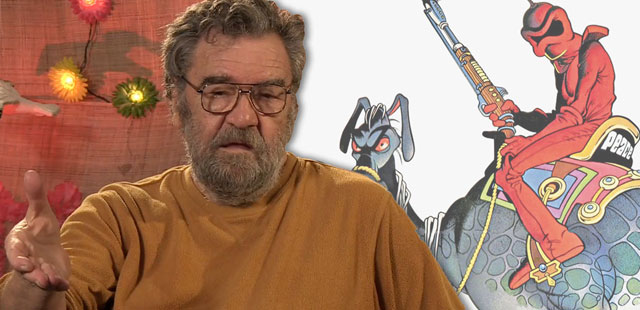

His influences were Bob Dylan, Jackson Pollack, Elvis Presley, Superman comic books, beatniks, jazz, Jack Kerouac, and the old school creators of cartooning and animation. This, coupled with the time periods he lived through, gave Ralph Bakshi the perfect storm of a foundation for his beliefs and the perfect medium to tell his stories. Ralph was never one to let himself be negatively influenced by others as he pursued his greatest joys and life’s work.

Ralph Bakshi was born on October 29, 1938 in Haifa, British Mandate for Palestine. (Author’s Note: As a history lesson, Israel was founded in 1948. Before then the land was known as British Mandate for Palestine.) It was only a year later, in 1939 that his family immigrated to New York City to escape World War II.

Ralph considers himself a New Yorker, and he grew up in Brownsville, an neighborhood in eastern Brooklyn. He played in the street, read comic strips and comic books and remembers no restrictions, no curfews, just freedom. He has said of his childhood, “We were poor, but we didn’t feel poor.”

In 1947, Bakshi moved to the Foggy Bottom neighborhood of Washington D.C. with his father and uncle, who were looking for business opportunities. Foggy Bottom was, at that time, a black neighborhood.

“All my friends were black, everyone we did business with was black, the school across the street was black. It was segregated, so everything was black. I went to see black movies; black girls sat on my lap. I went to black parties. I was another black kid on the block. No problem!”

The racial segregation of the time meant that Bakshi’s mother had to obtain permission for him to attend a nearby black school. Being the only white student was not a problem for him or the other students, but a teacher fearing that segregated whites would riot if they learned a white student was attending a black school, had him dragged from the classroom by police and several months later the whole family moved back to Brownsville.

When Bakshi was 15 he discovered the book Gene Byrnes’ Complete Guide to Cartooning at the public library.

“I used to go to the public library to see if I could find something to read. I was not a cartoonist at that point. I liked to draw, but I didn’t know that I liked to draw. It wasn’t anything that I thought I could earn a living at, my parents were immigrants and we were very poor. So I kept going to the library to find something to interest me once in a while and it also kept me off the streets in the winter which is, was very cold in Brooklyn and I’m wandering around and I pull out this book from the shelf and it’s called Gene Byrne’s Complete Guide to Cartooning and I looked at it and it was about how to become a cartoonist.

“Well, I just looked at it, stared for about 20 minutes in the library, it was the most beautiful thing I ever saw, ok. So I was going to take it home to read, right and it was that book that made me realize that cartooning was a way you could earn a living, that cartooning was a way you could be taught. I never had that idea. So, I was going to take it out.

“As I was going down the stairs, it was a two-story building and there was an open window that led to the street on the side, so I decided to throw the book out the window and take it home forever, I still have that book. But I didn’t check it out, I robbed it. But it had to be, cause I was never gonna bring it back anyhow. So either I was going to face all these letters with fines, at 5 cents a day or something, which I could not afford or just… I was never gonna bring the book back. I was so in love with this book I can’t explain it. I would have killed somebody, so it had everything to do with me becoming a cartoonist.

“I studied it and studied it and started to draw and then I went to art school because of the book. In other words, I was very young, I was not even in junior high, so I eventually went to art school because of the book. And that course taught me more. I would’t have gone to art school, my friends went to neighborhood public school, my art school was up in New York so the book had a tremendous, tremendous impact on me. It made the whole difference in the world and I still have the book.”

The art school Bakshi transferred to was the High School of Industrial Arts, a vocational school, where he graduated with an award in cartooning in 1957. In that school he learned a lot from his teacher, Charles Allen, a brilliant black cartoonist, who had a hard time getting jobs, but taught Bakshi a lot about what the world was like. After graduating he needed a job, “because how else do you take girls out… we used to take them to movies then,” so he took a job at an animation company named Terrytoons, where he fell in love with animation.

His first job at Terrytoons was as a cel polisher. “In the old days before computers, cels went to camera and the cels had to be clear, cels were what the animation was on… You had to polish the dust, the dirt off the cel or it would be shot and the animation would start to jump. It was an impossible job… the cels produced a lot of static and you’re sitting there wiping all day trying to get the dust off and my mother tried to have me clean the kitchen, you know the dishes, sometimes and I couldn’t do that well either. So I had a miserable time there…

“If you could survive the cel thing, they figured you stood a chance, so the next job was to paint the cels themselves. That was the next step up and that was $55 a week, that was a lot of money in those days, that was decent. And then you painted the cels for a couple years, I just sat there paintings cels.”

That was part of Bakshi’s journey towards animation. The real ladder of promotion was “polishing to opaquing, opaquing to inking, inking to inbetweening, inbetweening to assisting animation, and from assisting animation to animator and that’s already 10 years.” Bakshi, however, didn’t quite follow this track. He blazed his own trail from inking to animation.

“Terrytoons was the first company to go into TV animation, they did Tom Terrific. It was the first animated show directly for TV, and the place exploded. They needed animators like crazy. They didn’t know what to do, they’re calling everybody on the block and they’re promoting a few guys but they’re calling mainly guys out of work. They’re trying to get guys from California.

“So I’m sitting there upstairs – animators work downstairs and the ink and paint department’s upstairs, So I’m sitting there on afternoon, it’s summer, I grew up in Brooklyn, I’m really… I figured they need animators so bad, they got one sitting here, his name is Ralph Bakshi, right? So I pick up my desk… It was lunch time, so everybody was out to lunch or playing poker, which all the animators did, they played poker at lunch. So I pick up my desk… With Terrytoons you didn’t care, whatever you did during the day was good enough, at Disney he says, ‘Ralph you’d have to work too hard, you’d have to just be perfect for Disney.’ Here it don’t matter: you do this, you do that, you go home, you have a steak. As a matter of fact it was that attitude that allowed me to make Fritz the Cat, Heavy Traffic and Wizards, which were very low budget films, cause it was Connie [Rasinski] who taught me it’s not so much how slick they are, it’s how much heart they have.

“So that’s what Terrytoons taught me and that’s why I’m always indebted to Terrytoons and why I’m always talking about this great old studio that taught me that cartooning and heart are more important than slickness and lying to people.

“Well, Sparky the production manager runs into Connie and says, ‘What’s going on here’? ‘He’s animating.’ Sparky says, ‘He can’t animate.’ I said, ‘Well I ain’t going back upstairs, you’re going to have to fire me.’ And Connie says, ‘He’s a great animator, Sparky. The guy’s doing everything great.’

“So they go into the boss’s office and the union comes up and all the delegates come up and I’m in the boss’s office. Bill Weiss, who thinks I’m out of my mind – who picks up desks and goes downstairs and just starts animating – and calls Connie in and Connie says, ‘Yeah, he’s animating. He’s good, he’s OK.’ And the union says you got to fire Ralph or push him back and I said I ain’t going back anywhere. I said I’m doing this now. How you going to send me back to inking? So I’m doing the job, I’m doing the job. I mean you need animators and also they needed animators, understand they needed animators so my timing was pretty good, which was great.

“Everyone got to love me after hating me. All the guys upstairs, cause they promoted all the assistants so I can keep my job, they promoted the entire department to animation, so I can keep my job because Connie didn’t want to fire me and they needed animators. And what I did, what I did was prove and break the ice that you don’t have to be an assistant before you animate. In other words, the fact that I was able to go from inking to animation and do it, meant that the assistants can go from assisting animation and do it.

“There was always this thing of ‘when was a guy ready?’ So I had proven that this myth that a guy is ready only after he goes through this long chain of 10 years of apprenticeship. If a guy’s ready to animate, he’s ready. So I had proven that, which gave Bill Weiss the courage to promote all the assistants cause they needed animators desperately. Half those guys made it, half did not, but the place was an uproar that day from joy. The union was patting me on the back, so I went from being an ass and a degenerate Brooklyn guy to a hero because I gave a lot of guys promotions and also cause Terrytoons got all the animators they needed for the TV show. So that’s how I got into animation, I animated then a few years and decided I wanted to direct.”

At Terrytoons, Bakshi had one of the greatest moments of his career. He was directing and animating a feature called Silly Sidney. He had all of his animation piled up on top of his waste basket and went home for the evening. The next day he comes in and it’s all gone. The cleaning people had thrown out months of work. He hopped a train to Philadelphia to track down the truck number he got from the garbage company just as the truck makes it’s way to a paper mill, where it would be recycled.

“It’s 190 degrees in Philly and 500 degrees in the paper mill,” Bakshi recalls. He begins yelling at people when he gets there. It turned out that the truck his animations were on was dumping at that moment, so he ran up the stairs. At the top of the conveyor dumping the paper, he finds one extreme of his picture. He figures, this is hopeless and returns to New York.

“The boss did 20 minutes pounding his desk, he dropped his head… he hit his head on the table and just kept pounding. He didn’t know what to do with me and he looked up and I held up the extreme and I said, ‘I got one’. I think it saved my job. He just cursed me and said, ‘Get the hell out of here.'”

This kind of perseverance is found throughout Bakshi’s entire career.

He was eventually promoted to director and then moved to the animation division of Paramount Pictures, where he served as head of the studio for eight months before the entire division was closed. When he learned that his position was always intended to be temporary and that Paramount never intended to pick up his pitches, he refused the severance package that was offered by ripping up his contract and started Bakshi Productions in 1967.

Bakshi Productions started when all the shorts studios were closing down on the East Coast. Because of this, Bakshi was able to hire legends for his company, like John Gentilella of Spider-Man (1967) and Popeye; Nick Tafuri of Casper the Friendly Ghost and Popeye; Martin B. Taras of Casper; and James Tyer of Felix the Cat, Heckle and Jeckle, and Popeye, to name a few.

In 1969, Ralph’s Spot was created as a division of Bakshi Productions to produce commercials and a series of education shorts. Bakshi was uninterested in this kind of animation and wanted to produce something more personal, so he developed Heavy Traffic. But he couldn’t get anyone to fund the film because of his lack of film experience, so when he came across a copy of Robert Crumb’s Fritz the Cat he found something he could sell.

The film was promised $850,000 from Warner Bros, which didn’t allow any room in the budget for pencil tests, so the film was done without it. Bakshi had to test the animation by flipping through the animator’s drawings before they were inked.

In 1971, Bakshi moved his studio to Los Angeles, where he was railed against by the existing animators working for Disney. They took out a full page ad in The Hollywood Reporter, saying that his “filth” was unwelcome in the land that Disney built. This didn’t deter Bakshi and, despite an X rating, Fritz the Cat was released in 1972 and, to date, has grossed close to $200 million.

The success of Fritz allowed Bakshi to finally sell Heavy Traffic, which he released in 1973. Following Traffic was Coonskin, which he released in 1975 under much scrutiny and controversy, which led to a halt on his next project, Hey Good Lookin’, which he started to produce in 1974 and was completed in 1975. The film, however, would not be released at this time.

Bakshi’s street films, Fritz the Cat, Heavy Traffic, Coonskin, and Hey Good Lookin’ all have a certain quality to their sound. It’s rough, and it’s certainly not perfect. Back in the 70’s, all recording was done in crystal clear studios – no pops, not slurs, no street noise, nothing but the actor speaking lines. What Bakshi did was he went out into the city and recorded people in bars and restaurants with battery-run recorders to capture natural sound. Sometimes he would hire people to read the lines or he would ask them leading questions to get the line he was looking for in the movie as well as the ambient noise.

These are classified as Bakshi’s street films and they all sound natural, as if they were recorded on the street. “I want the moment, I want the moment. That’s all film’s about to me, you know the moment. When it happens, it’s very, very rare and should not be lost,” said Bakshi. Through his unusual methods, he captured many more rare moments than most.

These were also films for adults which was something Bakshi learned from Bill Mauldin. “Mauldin, one of my favorite cartoonist who taught me a lot… When I was a young man in High School, Mauldin – who wrote Willie & Joe for the Stars and Stripes in World War Two – was absolutely brilliant. His war stuff, his Willie & Joe were the greatest things ever done. He showed me that cartoons, too, could be adult. He showed me cartoons could make sense…” Mauldin’s sentiments, at least what Bakshi learned from him, are also in these street films, and each of the films that he’s done since.

Regarding the even more adult scenes in his films, particularly those depicted sex or nudity, Bakshi has said, “I had my tricks. What was important to me was the underlining discussions in Coonskin on racism in this country and dope and false revolutionaries…

“Each picture had some anger in it. But I knew that if I covered that with some tits and ass, some outrageous stuff, that I could get away with what I was saying because people would think that’s what great cartooning is, that’s why it’s in the films… None of my pictures need that stuff to survive. What I’m saying is that if you took the sex out of my films, it would still be my films. There wouldn’t be much different, no difference, but the studio execs… I manipulated them more than they manipulated me… I knew what I was doing to keep them off guard or they would’ve stopped me.”

In 1976, Bakshi pitched War Wizards to 20th Century Fox. He wanted to prove he could produce a “family film” that had the same impact as his other, more adult, features. George Lucas, who was also working on a film with “war” in the title, asked Bakshi to drop it from his title and name it Wizards. Bakshi agreed because Lucas had allowed Mark Hamill to take time from Star Wars to voice an elf in Wizards.

Bakshi released Wizards in 1977 and it began smashing box office records – unti until Star Wars was released, that is. Fox was distributing both films and, after seeing Star Wars break the records that Wizards had just set, removed Wizards from their theaters and replaced it. Who knows how well known Wizards could have done it it weren’t for Fox’s decision.

From the success of Wizards, Bakshi embarked on a trip to England to meet with J.R.R. Tolkien’s daughter to secure the rights to create a film based on The Lord of the Rings. The meeting was a success and Bakshi started filming. This movie did not have a cut-and-dry release. Bakshi wanted to release the film as The Lord of the Rings Part One as he only completed half of the trilogy. United Artists told him they were going to release the film as The Lord of the Rings because they felt audiences wouldn’t pay to see half a film. In hindsight, that’s clearly wrong, but this was the 1970s. Who would have anticipated that people would go and see half a film? The movie was released in 1978 and, although it’s not stated outright, seems to be one of the main influences on Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings. Some shots were even taken directly from Bakshi’s version.

Bakshi’s next film was American Pop, a film telling the story of four generations of musicians whose careers parallel the history of American music. Released in 1981, it made $8 million at the box office. The success of Wizards, Lord of the Rings, and American Pop finally gave Bakshi enough money to release Hey Good Lookin’ in 1982, seven year’s after its completion.

Although the original film combined live action and animation, the animation was replaced and outnumbered many of the live action sequences by the time the film was released.

Music is important in American Pop, but it also plays well in Fritz, Traffic, Coonskin, and Hey Good Lookin’. Bakshi’s song selection fits so very well within the context of their individual scenes in his films.

“First of all, I love music. I’ve always loved music. And I’ve loved various kinds of music. Music is part of our lives. It’s part of the soundtrack that what we all grow up with. Especially in my day. I don’t know today… I’m talking about yesterday and my day, which are the 40s, 50s, 60s, and 70s. Music is so emotionally important to the movie. It’s just as important as anything else. If the song is emotionally correct for a scene, the scene plays better. Or the scene plays better than it would have with a different song. So music is so critical to movies.

“I chose songs that I knew emotionally worked with these scenes that I wrote. Because whenever I listened to music while either driving in a car or sitting at a bar or listening to Coltrane or Billy Holiday and you daydream. If you don’t daydream to music, then you’re not listening to good music. So music is about dreaming, it’s about hope, it’s about the future, it’s about movies. It’s crucial and critical and more important than the writing in the film as far as I’m concerned.”

He also benefited from timing as he was able to buy all of the songs he needed “dirt cheap.”

“Why was that? Because everybody else was scoring their films. And why were they scoring their films? Because if they had a hit, they’d own the music, they’d make money from the score, they’d make their own records. I can’t release Billie Holiday’s ‘Yesterdays’ and make any money on it… I never considered that, that wasn’t the issue. The issue was what was right for the movie. I couldn’t believe the cheap prices I was getting and I had a low budget film, so I could afford to get anything I wanted.”

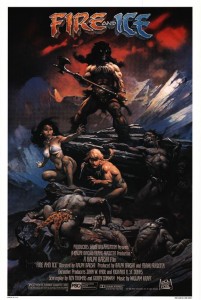

In 1983, Bakshi released Fire and Ice, a film collaboration between himself and the legendary Frank Frazetta. The film was based on characters co-created by Bakshi and Frazetta, but their names didn’t carry enough at the box office. As Andrew Leal wrote, the movie “stands as a footnote to the spate of barbarian films that followed in the wake of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s appearance as Conan” in 1982.

Following Fire and Ice, Bakshi attempted projects such as an adaptation of Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, and an anthropomorphic depiction of Sherlock Holmes and turned down offers to direct other films, including Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, which he passed to Ridley Scott who adapted it into Blade Runner.

During this period, Bakshi reread J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye and he sent Salinger a letter about adapting it into a film, but Salinger responded with a thanks but no thanks. At this point, Bakshi focused on painting and finished a screenplay for “If I Catch Her, I’ll Kill Her” a feature he’d been writing since the late 1960s. After finishing the screenplay, he could not sell the film and a few other promising projects fell through the cracks.

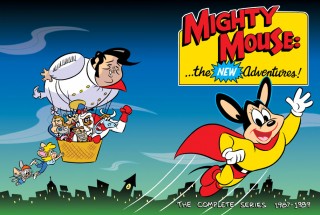

It wasn’t until 1987 that Bakshi returned to the spotlight, only this time it was the small screen. He had pitched CBS a few ideas and none stuck, but before he left the meeting, he pitched them Mighty Mouse, which they loved even though he didn’t have the rights.

It didn’t matter: things have a way of turning up for Ralph. CBS had purchased the entire Terrytoons library in 1955 and as such, they already had the rights to Mighty Mouse. “I sold them a show they already owned, so they just gave me the rights for nothin’!” said Bakshi.

Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures was wildly successful, thanks in part to some new animators Bakshi was working with, one in particular named John Kricfalusi. Kricfalusi ended up being the downfall of Bakshi’s highly acclaimed Mighty Mouse. Kricfalusi insisted that the artists add visual gags as they drew. And one such gag was a sequence in “The Littlest Tramp” episode where Mighty Mouse sniffs the remains of a crushed flower. Tom Klein, the editor, expressed concern for the scene so Baksh allowed him to cut it, but Kricfalusi was not happy with that decision and Bakshi followed his advice that it was harmless and told Klein to restore the scene. The episode aired October 31, 1987, without incident.

In 1988, Bakshi won an Annie Award for “Distinguished Contribution to the Art of Animation” and began production on a series based off of his own Junktown comic strips for Nickelodeon, who signed on for 39 episodes. This was as good as 1988 would get for Bakshi. In June, Donald Wildmon, head of the American Family Association (AFA), alledged that “The Littlest Tramp, depicted cocaine use and the AFA continued to claim that CBS had “intentionally hired a known pornographer to do a cartoon for children, and then allowed him to insert a scene in which the cartoon hero is shown sniffing cocaine.”

Bakshi responded, “You could pick a still out of Lady and the Tramp and get the same impression. Fritz the Cat wasn’t pornography. It was social commentary. This all smacks of burning books and the Third Reich. It smacks of McCarthyism. I’m not going to get into who sniffs what. This is lunacy!”

Despite his best efforts, receiving an award from the Action for Children’s Television, good reviews, and a ranking in Time magazine’s “Best of ’87” the show was canceled. Meanwhile, Nickelodeon scrapped Junktown but did air the completed pilot as Christmas in Tattertown, which was the first original animated special created for Nickelodeon.

There was a silver lining, as Bakshi was offered $50,000 to direct a half-hour live-action film for PBS’s Imagining America. Bakshi wrote a poem influenced by Jack Keroac, jazz, the Beat generation, and Brooklyn that served as narration done by Harvey Keitel, for This Ain’t Bebop, which was produced by his son Mark Bakshi.

“It’s the most proud I’ve been of a picture since Coonskin—the last real thing I did with total integrity,” Bakshi said. As a result of This Ain’t Bebop, Bakshi received an offer to adapt The Butter Battle Book by Dr. Suess for TNT.

Bakshi returned to big screen movie production, by pitching Cool World as a partially animated horror film. In the end, Cool World was released in 1992, but due to producer Frank Mancuso, Jr, son of Paramount President Frank Mancuso, Sr, the released film was far from the what Bakshi had originally pitched Paramount.

In 1993, Bakshi revisited “If I Catch Her, I’ll Kill Her,” which he renamed Cool and the Crazy and was done for Showtime’s Rebel Highway series. It wasn’t met with rave reviews. In fact, the nicest thing I’ve read was a line in Variety by reviewer Todd Everett who said, “Bakshi pulls strong perfs from a cadre of youngish and largely unknown actors.”

Bakshi was offered other projects, but in the end he disowned them as they were edited well beyond his own vision for them. In 1997, Bakshi premiered Spicy City on HBO, which only lasted six episodes due to issues between Bakshi and the network. Still, it came out one month before Trey Parker and Matt Stone’s South Park and can be named the first “adults-only” cartoon series.

That was it, or it might have been. Bakshi retired and returned to painting. In 2000, he started teaching an animation class at New York’s School of Visual Arts and he attempted to finance a low budget animated feature Last Days of Coney Island. In 2008, Bakshi moved to New Mexico and dove deeper into his painting.

Rumors have come and keep popping up about a Wizards sequel, or a completely redone Wizards trilogy, which was what Bakshi intended Wizards to be. Rumors were also spreading that Robert Rodriguez was planning to do a live-action Fire and Ice remake. At the time, who knows, this could have all been conjecture, but then Bakshi came back. In 2012 he started a short film series titled, Bakshi Blues. The first of the shorts was Trickle Dickle Down, which criticized Mitt Romney. This was just a taste as, in February 2012, Bakshi launched an inevitably successful Kickstarter campaign to fund Last Days of Coney Island.

In promoting his Kickstarter, Bakshi started to make the media rounds, confirming that Dark Horse Comics in looking into Wizards 2 and Robert Rodriguez could start filming a Fire and Ice live action remake when he’s finished shooting Sin City 2. This is great for fans of both animation and of stories that don’t talk down to you.

Ralph Bakshi’s legacy is far and wide. His influence is just as varied. He’s put his stamp on animation and technology with his use of rotoscoping, but it’s more than that. He paved the way for adult cartoons, some like The Simpsons and South Park to Cartoon Network’s Adult Swim programming block. Bakshi has contributed to modern media in a way that is immeasurable. The people that have worked for him have created or contributed to major features and companies like Pixar and DreamWorks and cult classics like Ren & Stimpy.

He’s always been an advocate for doing your own thing.

“Decide what you want and go after it. If you want to do your own thing, which I prefer because you can say things they don’t let you say at Disney, then that’s important,” Bakshi said at one Comic Con Q&A. Coming from a man who did it his way, you can’t help but want to go out and do the same.

In an interview for Crave online the following exchange took place better explaining his advocacy for personal choice.

“[Devon Ashby] I feel like that’s kind of your whole career – like, “F*ck this! There’s no reason I can’t just do it the way that I wanna do it!” I just love that.

[Ralph Bakshi] That’s my message. That’s my message to young people. Whatever you think about, you can probably do. As soon as you get afraid about it, and you start thinking, then you won’t do it.”

At a DragonCon in 2011, Bakshi stated that “in all respects” he feels that animation is superior to live action, and who could blame him for feeling that way. Animation is his medium of choice for storytelling and he has done it well for a long time.

“Animation can do so much: it can give you the big picture; it can give you the R-rated pictures, my kind of films; it can give you Warner Brothers films. It’s such a vast range and with all the computer tools today to help you, and the fact is the biggest business in Hollywood today is animation. The highest grossing films in the last five to 10 years are all animation. They’re all number one, two, and three of the highest grossing films ever, so animation is a huge business.” This quote proves that although he had retired to paint in New Mexico, he’s still keeping tabs on the industry and the technologies as the develop and grow.

He remains a consummate professional. He’s thinking that Netflix and YouTube will start financing films, as they are distribution hubs, and they’ve started to. They’re both developing their own series, but soon, they’ll be developing independent films as Bakshi’s predicting. The man is simply a once-in-a-generation talent.

You can’t summarize Ralph Bakshi. There simply aren’t words for the things he’s achieved in his lifetime, and he’s not done yet. Success, for him, is doing it his way and in that he’s been successful beyond his wildest dreams. He’s a beacon of truth and equality, of justice and storytelling. He’s a hero and one of the great influences on popular culture, and his movies are still playing to this day.

For more information on Ralph Bakshi, please visit his site www.ralphbakshi.com.

See the Ralph Bakshi Rotospective Archive.

I have used quotes and excerpts from The Nashville Public Library’s podcast Legends of Film: Ralph Bakshi, YouTube video Ralph Bakshi The Wizards of Animation, A Q & A from the 2012 Dragon Con, The Bat Segundo Show #214 featuring Ralph Bakshi and The Leonard Lopate Show on Ralph Bakshi, Animation Pioneer.