I saw my first Tucker at the America On Wheels Museum in Allentown, Pa., a few years ago. With just that taste, I found a thirst for more knowledge of this mesmerizing car, and I’m not what you would call a car guy.

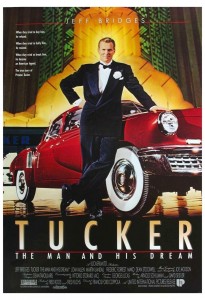

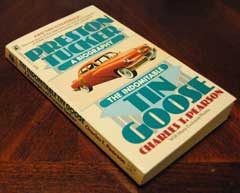

This lead me to a the movie directed by Francis Ford Coppola and starring Jeff Bridges as Preston Tucker in Tucker: The Man and His Dream. But the movie wasn’t enough, and I later ended up receiving Preston Tucker A Biography: The Indomitable Tin Goose by Charles T. Pearson as a gift from my family.

If the car itself started my fascination and the movie furthered it, then Charles T. Pearson’s words have left me wanting even more, although I’m not sure there is any more thorough an account then what he has included in this book.

I did not know Tucker was a policeman, that Tucker was flipping cars to make a profit, and that automobiles were his first and maybe one of his only loves. One statement sticks about above the rest; “Building an automobile that came as close as was humanly possible to his ideal was perhaps the one moral obligation Tucker recognized.”

In the fight – and it was a fight to get Tucker’s dream car built – he used his charisma, described by Pearson as “a knack of making friends because he accepted people at their face value and instilled confidence in others.” Those friends would ultimately help Preston Tucker win the first big fight of getting a War Assets Administration to give him a plant in which to build his dream car. They would also prove helpful in creating Tucker’s vision of a better engine and a safer car.

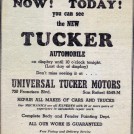

Some of the ads quoted in the book are as fascinating as car advertisements can be, such as “You’ll get the motoring thrill of your life” and “You’ll find nothing you’ve experienced before will compare with the smooth surge of FLOWING POWER from the Tucker rear engine drive … the new comfort of riding on the unique Tucker individual wheel suspension … the feeling of security you have in driving a car so precisely balanced that it almost drives itself.”

Once a car was built, the public went into a frenzy. The Tucker presentation at the Museum of Science and Industry at Rockefeller Center topped an estimated theatre equivalent opening of $42,000, more than Annie Get Your Gun had that week, which was just $37,000. It was also the only time receipts for that play at the Imperial Theater had grossed under $44,000.

Tucker’s charisma enabled him to get the best and brightest when building his company, but that was not without drama. When comparing the various experts and men with experience at big companies working with Tucker, Pearson wrote, “with Tucker it was different — he had less than a year to develop and get ready for production an entirely new automobile, and only a limited amount of money with which to do it. The veterans with Tucker simply couldn’t adjust. It was beyond them. It was completely outside their experience, and most of them were too old to change.”

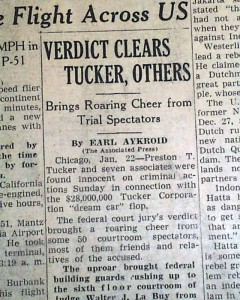

But the drama within his company was nothing when compared to the drama that was the Securities and Exchange Commissions (SEC) seemingly endless investigation of Tucker. Of the SEC report Pearson observed; “Yet that report was the beginning of a myth which persisted and grew after the trial was over. Like the report, the myth is a fantastic and unbelievable mixture of accusations, exaggerations, half truths and lies, magnifying Tucker’s mistakes and ignoring his very real accomplishments.”

It is still not known to me, or anyone for that matter, who was behind the SEC’s “out-to-get-Tucker” mentality. It could have been the government itself, but more than likely it was the automotive industry itself pulling the strings, but that answer is still eluding those who look into the story. Pearson himself, who worked with Tucker, seems to have summed up the entire debacle with three statements.

One: “It will sound like a pronouncement from the National Association of Manufacturers or the Union League, but it nevertheless is fact that courage and venture capital–just plain gamblers’ guts–created every major asset this country has today, from oil and minerals to invention and industry.” But with Tucker, regardless of who was behind it, everything he did was met with resistance and the strength of government financing.

Two: “Risk is the price of progress, and when risk is removed as an element of the American Economy, progress will eventually be limited to the work of captive scientists, in the narrow channels fixed by men whose chief concern is nation power and prestige.”

And three: “But if the nation still believes in private enterprise, even if only in theory, the government’s actions must be deemed a mistake, which if continued may well prove tragic.”

The truth of the matter is that regardless of who was behind it, the government’s overzealous approach to keeping Tucker from success was fairly unfounded, which is why he was never guilty of anything they put up against him during his time on trial. He even made another attempt at success, which was cut short by his untimely death due to cancer.

This book, did not sate my appetite for information about Preston Tucker, but it is a glorious insight into the man, the car, and his company.

I am still not a “car guy,” and I’m not sure that will ever change, but I am very much a Tucker man. His story was one that could have only happened when it had. The foresight he had in creating a perfect car may have been flawed, but many of the advancements he pushed to have in his car were adapted over time by the other big automotive companies.

He was almost 10 years ahead of every other car when the few Tucker ’48s were produced. Had he been able to get them actually into mass production and make a second generation of the car, who knows what we would be driving now? The rest of the competitors in his industry would have had to catch up with his advancements immediately. Maybe, we’d actually have flying cars by now, or completely clean cars? We’ll never know.

What we do know is that Tucker was a once-in-a-generation mind, and he was hampered at every turn by the very government that could have benefited from his ingenuity. Pearson takes a look at the man and it is a fascinating read. If you’re interested, be warned: after you read this book you will probably want to read the entire SEC report, but good luck finding them.

Look up the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s Annual Reports from 1947 to 1949 and you’ll find mention of the investigation and report, but not the whole report. In fact, in the 1947 Annual Report “Tucker” is mentioned six times, either the car, the man or the corporation, four times in the 1948 Annual Report and 13 times in the 1949 Annual Report. My best guess is that these mentions and the overviews in those Annual Reports are the most we’ll ever get to see until someone puts the whole SEC report online, which I assume is not going to happen. I can only imagine that the SEC is not proud of what it did, in hindsight anyway, and thus those documents will probably never be released.

In the meantime, pick up a copy of Preston Tucker A Biography: The Indomitable Tin Goose by Charles T. Pearson and for additional fun watch Jeff Bridges play Preston Tucker in the movie Tucker: The Man and His Dream. And don’t forget, many of the 51 cars that were made are still around, and most are even still driving around, many with most of the original parts! For a car briefly produced in 1948, that’s one amazing accomplishment. In fact, if you ever meet Francis Ford Coppola or George Lucas, ask them about their Tuckers. They are two of the few lucky Tucker owners and both were involved in the film, with Coppola as director and Lucas as executive producer.

Read the Secret File of technical information and quotes from Indomitable Tin Goose.