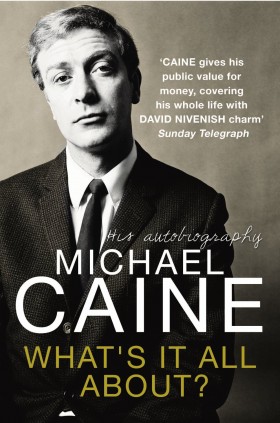

What’s It All About?

Author: Michael Caine

Release: October 5, 1992

Tagline: His Autobiography: Michael Caine

Publisher: Century

Genre: Biography

ISBN-10: 0091826489

ISBN-13: 978-0712635677

Synopsis: Michael Caine is the best-loved film actor Britain has ever produced. Here, for the first time, he reveals the truth about his childhood, his family and his hard-fought journey from London to Hollywood, bringing to life the lean years and the triumphs with astonishing candour. And with typical charm and humour he talks about the movies, about his relationships – on and off the screen – with other actors and directors, and about the memorable screen presence which is his hallmark.

Declassified by Agent Palmer: What’s It All About? Michael Caine tells All in his Autobiography

Quotes and Lines

“Well–what do you think of it so far?

It’s not too heavy for you is it? The told me not to write a long book or it would be too weighty and too expensive, so I’ve tried to keep the price and the bulk down. But there’s still a lot I want to say.

There have been something like 5,000 miles of newsprint and at least seven biographies on me (God knows why), so why add to all this? To set the record straight on my own record player for a change. I have long since stopped reading what is written about me; for the most part it has been wrong or misleading. I am not saying that I am a better or nicer person than I have seen portrayed and, heaven knows, this book is not a work of history or scholarship. But what you will read here is the real me–not for a change, but for the first time.

So what was it all about? I’m going to tell you.”

When they eventually began to mechanize Billingsgate, my father gave me the following advice: Never do a job where you can be replaced by a machine. Based on that advice I though how clever I was to become an actor, little realising I’d be facing competition from a tin shark, a green frog and the Terminator. The only other advice he ever game me was never to trust anyone who wore a beard, a bow tie, two-tone shoes, sandals or sunglasses. Having believed him for many years, you can imagine the panic I was in when I arrived in Hollywood. Never say never.

At around the age of four I set on a journey of discover that I haven’t finished yet. I was taken to see my first movie.

My father, on the other hand, took the view that if anybody hit me I should hit back even if it meant getting pounded. “There is no shame in losing a fight,” he told me. “There is only shame in being a coward and refusing to fight.”

…a tie. This instrument of torture was drawn tightly around the prickly collar that was already causing a rash around my neck. I hated this tie so much that I have never worn one since unless it was absolutely necessary. (Today I own five restaurants and in none of them are you required to wear a tie.)

I was also told that I should never let anybody call me a “schmuck.” When I asked what this meant I was told that only a schmuck would ask a question like that.

The final polish on the education at Grocers was music. Everybody seemed to be taking violin lessons, and in order to be assimilated into this new society, I took the violin up too, with such disastrous results that the teacher refused to accept payment for my lessons at the end of the term. “Goyim” are not natural violinists, I was told, and I could not agree more. But at least I’m not a schmuck.

…my only interest was in the unattainable, which was perhaps the reason why I found it so difficult to attain anybody at all.

“If after five hands you haven’t worked out who the pigeon in the game is,” Dad said, “it’s probably you.”

We felt we were heroes. We had met the enemy up close, and we had survived. For my own part, that night has always been important to me, because although I hadn’t killed anyone or proved myself to be a hero, I had faced what seemed to me to be certain death and I had not been a coward. And I had learnt something about myself which I would value for the rest of my life: if anyone takes me, they’re going to have to pay. In fact, I thought as I walked to my bunker, smiling to myself, not only will they have to pay, but the price will be fucking exorbitant.

…the band suddenly changed its tune and struck up our own regimental march which brought about an instant change in our attitude, because this was our march and we found that we did have some pride in what we’d been and what we had done. Without thinking, we all straightened up, formed a line and very smartly marched out of the army forever singing our own words again: “Here we come, Here we come. Bullshitting bastards every one.”

The world leaves us to our own devices–until one in a thousand of us survives this baptism of fire and then, it seems to me, they resent us when we are successful. Our job has no guarantees and that is why the survivors are paid so much.

…The Caine Mutiny. I looked for a moment and decided that was the one, for several reasons. “Caine” was short and sounded easy with Michael, and it was a word with which everybody was familiar, particularly those of us who had been through the British school system. The word “mutiny” in the title also appealed to me, because at that time I was extremely rebellious and angry, but I couldn’t call myself Michael Mutiny. There was another reason for my choice, a Biblical one. Cain was the brother of Abel who was cast out of Paradise, and I felt a great sympathy with him at the time.

The moral of this little tale is good for everybody, not just show people, and it is this: if you want to do something with your life, never listen to anybody else, no matter how clever or expert they may appear. Keep your eyes open and your ears shut, and as the Americans say–“Go for it.”

I have always disliked what is called the kiss-and-tell type of autobiography. Firstly because I have been the victim of several, and I have always felt in some way betrayed, and secondly because if you are a man and the book is by a woman, there is invariably an assessment of your sexual prowess. While I am not afraid of this, I have a professional aversion to being reviewed, no matter how favourably, for a performance for which I was not paid. Especially when the critic was in the show.

I was once asked in an interview: “How would you sum up your life in one line?” and I answered, “All my dreams came true.”

I may be a member of a country that was one of the greatest colonial powers in history, but me and mine–and the many thousands like us–got nothing out of all this. As far as I can see, we owe nothing to any race on earth, colonial or not, because we never took a thing from anybody.

And so my debut in major motion pictures was not me at all but a prop man named Ginger.

The stakes were high now; in my case particularly so since for all these years I had maintained that all I needed was a real chance on the big screen and then I would show everybody not only that I could act well but that I also had that indefinable something, “star quality.” The closest definition of this was one I heard from David Lean many years later. He told me, “When you are cutting a scene with an excellent actor you can cut as he finishes the line; but with a star you can hold the shot for at least another for frames, because that is when the magic happens.”

I learned a couple of valuable lessons, though. One, not all movie executives know what they are talking about; and two, very few people can understand rushes when seen in isolation from the rest of the work. One time-honoured epithets of the movie industry when a film opens and bombs is, “Well, it looked good in the rushes.”

I knew that I could not buy her affection, but I could buy her interest until I could afford time, for with children time is the currency that buys affection, and if you spend enough of it you might buy love.

Several weeks later he came rushing in full of good news. “What’s happened?” I asked eagerly. “I’ve done it,” he said. I did not understand. “Done what?” “You remember all those blokes who said we were queers?” “Yes,” I answered, even more puzzled. “Well, I’ve screwed all their girlfriends. Now they can say what they like!” He smiled proudly at a good job well done and went back to moping over the photo of Jean. I reminded myself never to cross Terry.

Everywhere you went there was someone who was going to do something great–if not in show business then in something else, and if not now, soon. The energy was like a giant express train of talent that had no stops or stations. When you were where you wanted to be you took your life in your hands and jumped and that is how the people appeared, as if from nowhere. You met someone one day and the next they were all over the papers from some reason they had jumped from the train and landed safely.

Let me tell you abot the two minutes that changed my life and the guy who so generously gave me those two minutes. His name was Harry Saltzman and he, together with “Cubby” Broccoli, was responsible for the fabulously successful James Bond series…”Have you read a book by Len Deighton call The Ipcress File?” Harry remarked, chancing the subject suddenly. As it happened, I was halfway through it at that time and I told him so. “I am going to make a film of it. How would you like to play the lead?”

I remember my talk with him with embarrassment now, considering that at the time he was ten times richer and infinitely more successful than I. I gave him a lecture on the way he was doing business, and the gist of it was something that I really believe you must do if you want to be mega-rich. It’s simple. You must have something that is working for you while you are asleep. “For instance, successful musicians have got it made,” I told him. “Their records or music are being played all the time, every day, somewhere in the world. No matter what they are doing, they are still making money. You are a great hairdresser,” I lectured him, “but you can only charge so much for a hairdo and you can only stand on your feet for so long so there is a ceiling on the amount of money that you can make. So, you’ve got to make shampoos and other products that work for you while you are asleep.” He agreed with me and told me that was what he was going to do.

One night I got no sleep at all, as over and over again for hours on end right until dawn he worked on the same tune. I slept for short periods during the night and finally woke up with a start when the music stopped. I had grown so used to the noise that the silence had disturbed me. I decided to get up and make myself and John, if he was still awake, a cup of coffee. I went out into the living room and found him slumped exhausted over the piano. He had obviously finally finished the one tune that he had been slaving on all night. I made him some coffee and he played it for me as the sun came up and warmed the room. Not only was I the first person to hear this tune, I heard it and heard it all night long. “What’s it called?” I asked him when he finished playing. “It’s ‘Goldfinger,'” he replied–and fell fast asleep at the piano. Shortly after that my house in Albion Close was ready and I moved into my own home for the first time. A unique joy. That night I fell asleep in my stranger new surroundings humming “Goldfinger” to make myself feel at home.

He then went on about our film censor, who spend most of his time removing shots of ladies’ naked breasts from films in case children should see them. This, Ken scoffed, was ridiculous–since children were the very people for whom ladies’ breasts were invented.

Our first problem was the fact that the book had been written in the first person, and the narrator had no name. One evening at the mansion we were sitting around discussing this when Harry said that this spy was to be the antithesis of James Bond: a very ordinary bloke, someone who could mingle unnoticed in a crowds and who should have and ordinary boring name. “What’s the dullest first name we can give him?” asked Harry. Charlie Kasher, his partner on this film, myself and a couple of other people sat there meditating about his for a while and then I suddenly, without thinking, blurted out: “Harry is a pretty dull name.” There was a stunned silence as my faux pas registered, and all eyes turned to Harry, who, for all his friendship and kindness, had a ferocious temper. He stared straight at me for a moment and then started to laugh. “Let’s call him Harry, then,” he said. “My real name is Herschel.” Audible sighs of relief hissed round the room as the danger passed. Now we needed a surname. We all started to go through the dullest names we could think of–Smith, Brown, Jones, etc. None of them felt right. Finally, Harry said, “The dullest person I ever met was called Palmer.” So that was it–the character was christened Harry Palmer.

No matter what you expect, things never turn out quite like they should, do they?

…as the threats of nuclear oblivion came and went with monotonous regularity. I think that part of the rationale of that period in London was along the lines of “To hell with everything–we may not be here in four minutes’ time.”

Sometimes I felt that I was dreaming, but pinch as I might I never woke up from the dream that I was living, and probably still haven’t, if the truth be known.

One day, in desperation, I decided to venture across Sunset Boulevard and walk in the pretty little park opposite the hotel, and this marked the real start of my life in Hollywood: I saw my first movie star there up close. As I was walking round the fountain in the middle of the park, I noticed a little old man being taken for a walk supported by a very pretty nurse. I must admit that it was the nurse who first attracted my attention, but as I wandered slowly over towards them to get a closer look, I recognized the little old man as Groucho Marx. There he was, my first film star in Hollywood, so they did exists and I was in the right place after all. I was beginning to doubt it as loneliness and the hot sun started to affect my sanity. As I passed I could not help staring at him and he said a very pleasant “Good morning,” to me. Apart from the hotel staff he was the first person to ever address me socially in Beverly Hills.

It was starting to get cold in England so off I went to represent my country as Alfie once again. I was beginning to feel that I should be given and Olympic-style T-shirt with SCREWS FOR ENGLAND printed on it, above a pair of crossed ladies on a bed of Union Jacks as a logo . . .

You can wind up, as I do when a good role comes along, absolutely prepared, having worked right up to date, or you can sit there waiting for it for five years, scared and rusting. No one remembers unsuccessful pictures because no one goes to see them.

“No, I don’t think he is gay, Michael,” and started to walk away. Suddenly he whipped round and added in a loud whisper, “Mind you, I think he’d help out if they were busy.” I love that line.

I asked Bob afterwards what would have happened if the old man had dropped dead during the festivities, which had looked very likely for a time. He told me with a straight face that they had a hundred magicians, one for each table in the room and if Mr. Zukor had dropped dead they would all rip the white cloths off the tables to reveal black ones underneath.

“You must never ever lose face,” he told me. “With your display of tempter just now you did exactly that–and it is only the first day of shooting. Not only have you lost face, but it will remain lost with these particular people in this situation and you will not regain it until the project ends. We all lose our tempers sometimes,” he continued, “but you muse never lose face in front of strangers. You belittle and demean yourself by showing such a great and personal emotion in front of people whom you do knot know intimately, and the loss of control shows the other person that you are weak. Control, Michael,” he said. “If you cannot control yourself, who can you control?”

…as we flew into the seventies I thought of the original phrase form which John Osborne had got his title Look Back in Anger. It was: “Never look back in anger, always look forward in hope.”

“My garden is my psychiatrist,” I told him, and I really believe that. Whenever I get in a state about anything, which is often in a business like mine, I just go walk , or sit, or work in the garden and somehow it all seems to come out right in the end–just like a movie.

It was a real oddball of a movie that never quite worked. While its heart was in the right place, in a business where wallets are kept over the heart this did not count for much. Pulp never made any real money, but I remember it with affection.

He had white hair and a white beard separated by smiling blue eyes that looked as though they had seen it all and decided that it was okay anyway.

The logic, though not typical for a westerner, was, after a little thought, unmistakably correct and a lesson for us all. Time is not something that is passing but something to be spent–wisely, of course.

Eventually Sean broke the silence, and in a very simple way he summed up the different attitudes between Easterner and the Westerner towards time and distance: “I can see now why no Arab has ever won a hundred-yard sprint in any international competition.”

“Why is that, Sean?” I asked, accustomed to the very shrewd pronouncements that he occasionally passed on to the rest of us.

“Because if you said to an Arab, can you run from here to there”–pointing to a spot a hundred yards away–“he would say to you–why should I, because it is exactly the same over there as it is here, and I have got all day to get there anyway.”

Sean is a very logical man, and there was no escaping the logic in this statement. I think he summed it all up beautifully.

We furnished the house and fixed it up in no time at all–another contrast with life in England, where it was impossible to get anything done immediately and difficult to get anything done at all.

There are unpleasant people there, as there are everywhere else, but you just don’t go to dinner with them–if you do, you pretend that they are not and they are usually so surprised that they manage to be nice for the evening. Try it, it works.

…acting, which is the theatre, to behavior, which is film acting.

I have often described the difference between these two states as follows: a standard of living is two cards, two television sets, two refrigerators, one psychiatrist and some pills. A quality of life is one car, one television set, one refrigerator and no psychiatrist or pills.

George Burns had the funniest line of the evening. He said, “Acting is simple. All you have to do is be sincere and then learn to fake it.”

…talking to him about the time he lost his title to Joe Frazier. I was present at that fight, I told him, and I could not understand why, towards the end, he seemed just to stand there and take the punches without putting up any defense. Ali’s answer has stayed with me to this day. He told me that Frazier had hit his arms so often and so hard that he had in fact paralyzed them. At the end of the fight Ali could not even lift them to defend himself.

People also think that he will say funny things all the time. Not so. Like all comedy writers, he doesn’t say funny things, but listens to hear if you say something funny that he can use.

Shakira and I are very social animals; we base our life in part on a quotation from St. Augustine, who said: “Life is a book and he who stays at home only reads page one.”

Love scenes are also difficult from married actors’ point of view. When your wife sees a film–and you can be playing anything from a serial killer to an SS officer–she will compliment you on a wonderful performance. If you put the same realism into a love scene, she will say: “You’re not that good an actor, you must have fancied her!” In my own defense I’ve learned to be slightly bad at love scenes.

To each of us he dispenses wisdom, hospitality and experience and to me, once, a lesson in his beloved priorities. He asked me to dinner on evening and I had to tell him I was dining with someone else. He asked me who it was and I told him. “You can’t have dinner with him,” he said, “he’s a lunch.”

I remember an American once saying to me that the Americans made moving pictures and the British made talking pictures and I agree with him.