At first, I thought that Fighter would be a fictionalization of the Battle of Britain similar to what Len Deighton had done with the fictional bombing run in Bomber. But I was wrong in the best of ways. It is not a fictional account, but a detailed dissection of one of the turning point air battles of World War II.

It amazes me that Deighton, a master of fiction, wrote such a comprehensive history on the Battle of Britain. A battle, that behind the scenes, was marked by ineptitude, hubris, politics, and more than a few elements of self-sabotage on both sides as to appear, in a vacuum, as more fiction than fact.

A few quotes to support that statement, first, the lack of knowledge. “The key to the story is that the air commanders before the Second World War had very little previous experience to draw on.” And why was that? “There had never before been a battle in three dimensions, and never a battle moving at such speeds.”

Additionally, “The tactics of the air war–as they emerged–were not very much different from the lessons that had been learned in 1914 to 1918. Height was still the trump card, with attacks out of the sun the most reliable tactic. Heavier fighters, that accelerated more quickly into the dive, were often forgiven other faults. Acceleration in level flight is a quality not listed in any aircraft specification, but for a pilot coming under fire, it often meant the difference between life and death.”

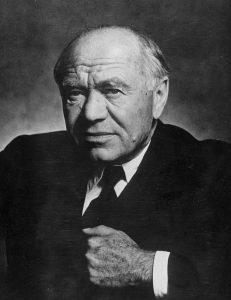

General Giulio Douhet

Here again, the lack of knowledge is shown by a piece of fiction being the main point of contact for the creation of battle plans.“Like many high ranking airmen, and manufacturers of bombing aircraft, Göring subscribed to the theories of General Giulio Douhet, an Italian who believed that armies and navies were best employed as defensive forces while bomber fleets conquered the enemy. Just before he died in 1930, General Douhet wrote a futuristic story called “The War of 19–.” Often quoted but seldom read, Douhet’s words had such profound effects upon the German and RAF High Commands that they are worth examining. Written in the documentary manner of H. G. Wells, Douhet’s story described how an “Independent German Air Force” fought great aerial battles against the Belgian and French air units. “There was no doubt that the enemy’s purpose was to make the mobilisation and concentration of the Allied armies as difficult as possible,” said Douhet’s imaginative action. The Allies replied with “night-bombing brigades” that attacked German cities with explosives, incendiaries, and poison gas.”

Next, on the fictions already written, “History is swamped by patriotic myths about the summer of 1940.” Continuing with a statement too true for The Battle of Britain, “Petty jealousies and vicious vendettas flourished as empires were built.” In fact, one of the defining issues of the battle may be more importantly associated with the fact that “while all bureaucracy is devious, military bureaucracy is conspiratorial.”

And of course, the Battle of Britain was supposed to be the catalyst for “Sea-lion” the name of the invasion of England by Germany, but “Sea-lion was contemplated, said the jokers afterwards ‘but never planned.’”

All this when “In 1940 there was honey still for tea, in the world’s last romantic battle.” A battle where it is important to note that the German Bf 109 had “a mere nine seconds of gunfire compared with the RAF’s machine guns which could deliver fourteen seconds of fire.” And when the main fighters of the Germans “the Bf 109 averaged about 90 minutes’ flying time. But climbing and getting into formation, as well as finding airfields on the return, meant that German fighters never had more than about 30 minutes over English soil.”

Messerschmitt Bf 109

This decisive battle didn’t quite have these extremely intricate long drawn out dogfights that the movies would have us believe.

But this is a realistic version of history, that doesn’t overlook anything. As written in the forward by British historian A. J. P. Taylor, “In the last resort battles are decided by the men and machines that take part in them. I am afraid that many of us who write about war neglect this side of it and write in great sweeping terms. Len Deighton does not.“

Deighton spares no expense to the details. He goes into not just the mechanical specifications of the aircraft involved, but their individual histories, even if truncated. Those aircraft include Hawker Hurricane, Supermarine Spitfire, Dornier Do 17Z, Dornier Do 215, Heinkel He 111, Junkers Ju 88A, Junkers Ju 87B, Messerschmitt Bf 109, and Messerschmitt Bf110. Deighton goes back to before the Wright Brothers in his attempt to explain where these aircraft and the theory of design for these weapons came from.

He also details all four phases of the battle:

“PHASE ONE Starting in July there was a month of attacks on British coastal convoys and air battles over the Channel: Kanalkampf.

PHASE TWO From 12 August-the eve of Adlertag (Eagle Day)–came the major assault. Göring and Nazi propaganda writers called it Adlerangriff (Eagle Attack). It continued for just over a week.

PHASE THREE What the RAF called “the critical period,” in which RAF fighter airfields in south-east England were priority objectives. This lasted from 24 August until 6 September.

PHASE FOUR From 7 September. The attacks centred on London, first by daylight and then by night.“

And let us not forget the “characters” of the battle, being those in charge.

Lord Beaverbrook

For the British, it was Sir Hugh Dowding, who “was no paragon. Too often he resorted to caustic comments when a kind word of advice would have produced the same, or better, results.” While for the Germans it was a cast of characters mainly Hermann Göring.

My personal favorite is the controversial Lord Beaverbrook, who “‘ran his Ministry as he ran his newspapers. Over his desk there was displayed the notice “Organisation is the enemy of improvisation.’” And is quoted with two other brilliant deductions;

“Better a stringency in spares and a bountiful supply of aircraft than a surplus of spares and a shortage of aircraft,” explained Beaverbrook.

“…as Beaverbrook reasoned, ‘industry is like theology. If you know the rudiments of one faith you can grasp the meaning of another.’”

And while Beaverbrook may be a compelling figure who was not a General, on the German side, based upon Deighton’s research, it is a German named Helmut Wick who is a standout figure in this book. “When Wick’s unit was paraded for a visit by Feldmarschall Sperrle, Wick was gently told that his ground crews were unmilitary in appearance. Wick asked his Air Fleet commander innocently if he didn’t think that refuelling, rearming, and servicing the fighters, to maximise operational status, wasn’t more important than getting a haircut.”

Two WWII Supermarine Spitfires

To summarize, this book is hard. While it is a piece of nonfiction, it reads like fiction. From the fact that a piece of fiction written by “Douhet smoothly concluded that ‘No one can command his own sky if he does not command his adversary’s sky’” to the quote “Churchill honoured the fighter pilots with the immortal phrase, ‘Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.’”

But perhaps it comes down to a quote by Oberst Karl Koller, Staff Officer and later Göring’s Chief of Staff, “The Reichsmarschall never forgave us for not having conquered England” and Churchill’s “The odds were great; our margins small; the stakes infinite.”

If you are a history buff, this is the book you’re looking for where it pertains to World War II. For me, it was one of the most compelling pieces of non-fiction I’ve ever picked up on military history.