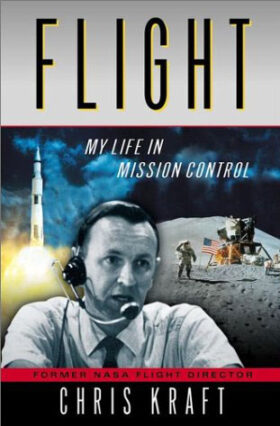

Flight

Author: Christopher Kraft

Release: March 1, 2001

Tagline: My Life in Mission Control

Publisher: Dutton

Genre: Aeronautics, History, Technology, Biography, Science

ISBN-10: 0525945717

ISBN-13: 978-0525945710

Synopsis: One of the architects of the U.S. space program recalls his most exciting moments at mission control as he guided heroes like Alan Shepard and John Glenn on their historic missions.

Declassified by Agent Palmer: Chris Kraft Takes You Behind the Origin of Mission Control in his Autobiography Flight: My Life In Mission Control

Quotes and Lines

To the thousands of dedicated people in the industry, academe, and government who contributed to the success of one of man’s greatest adventures.

In mission control, nobody lies to Flight. They tell what they know, or they tell me their best informed guess. There’s only one other option: “I don’t know, Flight.” Anybody who gives me that answer more than a few times will be looking for a new job.

“It’s not fatal to change your mind as you discover more about your own interests.”

It’s not fatal to change your mind.

I was never one of those kids who knew from the beginning what he wanted to do in life. But what I lacked in brilliance, I made up for in luck, and I found my niche.

Chuck Mathews was in charge of the operations section of RFP. “Our part’s simple,” he told us. “Chris, you come up with a basic mission plan. You know, the bottom-line stuff on how we fly a man from a launch pad into space and back again. It would be good if you kept him alive.”

“Be innovative,” he’d tell us. “Don’t be afraid to try something new.”

Bob Gilruth would always be a shadow compared to the names that became famous. But his guidance and his management were anything but shadowy; he ran America’s man-in-space programs from their moment of creation, and all that flowed from that day forward came because of his vision and his leadership.

I look back now and shake my head. Today the government may spend a year thinking about, then preparing, a Request for Proposal. There’s a cover-your-ass mentality that has to dot every i, cross every t, and get some lawyer’s initial on every page. It may be six months before contractors have to respond. Then the evaluations stretch toward infinity. By the time a major contract is awarded, the original idea may be several years old, technology has passed it by, politics has intruded and changed the mission or the rules, and the inevitable redesigns consume more years. The International Space Station is a perfect example of a bad plan followed by more than a decade of middled modifications in both design and mission. If we’d had a 2001 bureaucrat running the Space Task Group in the late fifties, the Russians would have clobbered us in space, and the last forty years of the twentieth century may have played out far differently than they did.

With NASA only a few months old, American industry and American technology were embarking on a voyage that would be the high point of the twentieth century. We still couldn’t see that far ahead. Just seeing the day after tomorrow was hard enough.

The question of what to call our future space men had been settled by now. It came down to astronaut or cosmonaut, and astronaut won. When the Russians began calling their space men cosmonauts, we couldn’t have been happier. The nomenclature was a simple way for the world to know who was who.

We were overwhelmed with emotion, with a sudden new sense of enormous adventure, with pride and awe that the president had dared to stand there and say such a thing. Then slowly and with a deep concern, our sanity returned.

I remember the old saying about engineers: They’ll overestimate what they can do in a year and grossly underestimate what they can do in then.

I hope so, I thought, because we’ve still got a lot to do on Mercury.

And the baseball fan in me kept thinking of the old Brooklyn cliché: “Yesterdays’ heroes are tomorrow’s bums.”

I’m still confident today that we had the kind of skilled engineers in the early sixties who could have built both the transport vehicles and a space station operating in Earth orbit. If we’d gone that route, we would have developed even better vehicles for exploring the moon, Mars, and probably much more. Certainly we could have done it with less risk, less money, and more productivity than the way things turned out. We would have had American men and women leaving their footprints on Mars in the 1990s. Instead we’re still waiting for our first space station.

Bob Gilruth once said that if Jack Kennedy had been older and wise, he would never have committed us to landing on the moon. The same was true for all of us working for Gilruth. If we’d been older and wise, we would have known that we couldn’t get it all done. But we weren’t. So we did it.

Gemini III was a complete success. But it was tainted by the corned beef episode. Some doctors and a few outraged congressmen complained that Grissom and Young had compromised medical tests with their unauthorized lunch. They hadn’t and I certainly saw no problem. No matter how brave or focused an astronaut is, there’s a tension in space flight that none of us on the ground can truly appreciate. A moment of diversion up there is no bad thing.

It would have been easy to chew him out for disobeying a mission rule. But we didn’t hire those guys because they always followed the rules. By training and by personal inclination, test pilots react to events, and sometimes that means ignoring the book.

By year’s end, the verdicts from the public and the press were unanimous. America was clearly ahead of the Russians, they said, and was going to have no trouble getting to the moon. That set me to brooding again. One more time, we’d made it look too easy, and now our critics were our biggest fans.

Once again, I was in the back row with Bob Gilruth, an uneasy watcher instead of an active participant.

Gemini seldom gets proper credit in the eyes of space historians, except for those few who were there to see for themselves. We were so focused on the operational aspects of flying one mission while getting ready for the next that we only saw the larger context when we had time to look back at what we’d done. Myu view is simple: Gemini bridged the technology gaps that made Apollo possible. Without Gemini, the Kennedy goal of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth by the end of that marvelous decade would not have been accomplished.

Nothing inspired introspection more than failure.

I never saw a Saturn fly. I never saw any rocket lift off, except on television, in Mercury, Gemini, or Apollo. My place was in mission control, where the action was. Maybe I missed something. But I couldn’t be in both places at once. I’d made the right choice and never regretted it.

Sometimes the common understanding of human greatness exceeds the bitterness of dissent.

Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo forced advances in digital computers that would otherwise have come later, or even not at all. NASA revolutionized electronics.