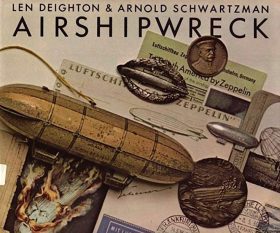

Airshipwreck

Author: Len Deighton & Arnold Schwartzman

Release: March 1, 1979

Publisher: Holt, Rinehart & Winston

Genre: History, Technology, War, Flight

ISBN-10: 003046451X

ISBN-13: 978-0030464515

Declassified by Agent Palmer: Airshipwreck by Len Deighton is about the downfall of the magic of Zeppelins

Quotes and Lines

And yet within living memory few men doubted that lighter-than-air craft were the only practical air transport for passengers and freight. The invention of the steam engine encouraged men to think that powered flight was possible. The development of the aeroplane was slow: the way in which these ‘heavier-than-air’ machines could lift into the sky was mysterious, and for most people it remains so.

For many years airships dominated the air routes. By 1936 the regular schedule airship service between Germany and Rio de Janeiro and the airship service between Germany and New York were still the only transatlantic air routes. No aeroplane could perform such a task. The following year the Hindenburg burned and decades of accident-free airship flights were obliterated by awesome film and photo of the burning Zeppelin. And yet the aeroplane could still not provide air routes across the Atlantic. It wasn’t until 1939 that heavier-than-air machines carried fare-paying passengers on the Atlantic route — a full twenty years after the R43 airship had crossed.

It wasn’t until the middle 1950s that airlines offered passengers a direct service across the Atlantic.

For me the airship has a magic that the aeroplane cannot replace. The size is awesome, the shape Gothic, a pointed arch twirled into a tracery of aluminium. And the reality is not disappointing.

So where did the dream go wrong? No two experts exactly agree. Certainly time was the airship’s enemy. ‘Airships breed like elephants and aeroplanes like rabbits,’ said C. G. Grey, editor of the Aeroplane, in 1928, rightly predicting that evolution must favour aeroplanes.

In this book, with the help of experts, I have told the story of the airship’s failure. It shows the daunting task that the airship designer faced. Perhaps all simple acts of faith bear an imprint of absurdity, and you’ll find it here. But the book is intended as a tribute to the master builders and their aluminium marvels. This generation of engineers dared to build their cathedrals in the sky; no wonder then that so few of them stayed there.

In flying, as in the other arts and sciences, theorists have always outnumbered practicians.

…the Robert brothers, who were already selling a very fine, and extremely light-weight, rubberised silk. Before tailoring it into an airship for the Duke of Chartres they were prospering from the strictly illegal manufacture of contraceptives.

Even newspapers that had not been covering the flight of the LZ4 splashed the story of its destruction. A 24-hour flight would have given the Zeppelin company government finance. Now the 70-year-old Count was penniless and depressed. But the disaster brought gifts of wine, hams, clothes, the contents of money-boxes, legacies and advice. Within one day, money equal to the cost of LZ4 had arrived.

Count von Zeppelin’s airships always attracted a crowd and, but the time LZ4 flew, the old man was a popular celebrity. So the loss of this great airship saddened the whole of Germany.

The LZ6, hurriedly lengthened to replace Deutschland, thereby became the first passenger-carrying rigid airship. But after only a few weeks she was destroyed, when a careless mechanic, using petrol as a cleaning fluid, caused a fire. Another mechanic threw more petrol on the flames, believing it was water.

The LZ37 was a small pre-war design, built in the shed at Potsdam, Berlin. It was to be the first Zeppelin brought down by an aeroplane.

Visible in the air and on the ground, vulnerable to aircraft and to weather, the airship was no longer an effective war weapon. But as an engineering achievement, the airship was an astounding success.

Shenandoah was based upon the design of the German navy’s L49 which had been force-landed in France in October 1917. But the height climber had been considerably modified: she needed and extra section because the Americans filled her with non-inflammable helium which had less lift. Shenandoah was the first airship to use it.

They were attempting the impossible. The cold front was far too long to escape. By now Akron was flying through heavy rain, and the barometer needle swung crazily as the storms approached. There is nowhere else in the world that has cold fronts, and the associated phenomena, like this part of the USA. (That part being the mid-Atlantic region.)

There was virtually no life-saving gear aboard the Akron. In the Atlantic ocean that night even strong swimmers had little chance against the big waves and the cold that froze them to the bone. Of the 76 men on Akron, only 3 were saved.

Commander Herbert V. Wiley, one of the only three survivors of the Akron disaster, was captain of the Macon when that crashed into the sea two years later.

The water was not cold and there were ships nearby. The airship was plentifully equipped with life-saving gear. Of the 76 men on the last flight of Macon, only 2 were lost.

By 1963 the Zeppelin company had no rivals as designers, builders and operators of rigid airships. As well as her famous flights — round the world, to the Arctic, Middle East and eastern Europe — the Graf Zeppelin airship had established a regular passenger service between Germany and South America. As 1936 ended, Graf Zeppelin had flown a frand total of 1 million kilometres, 16,000 flying hours in 578 successful flights.

During 1936 Hindenburg made ten schedule flights to New York (Lakehurst) and seven to Rio.

In June 1974 I spoke about the Hindenburg disaster with Captain Hans von Schiller who, at the time of the disaster, was the captain of the Graf Zeppelin airship, flying back from South America. Reluctant to commit himself to any theory, von Schiller made the following comments. His vast experience of airships, and his keen mind, provide what I believe to be the most probable explanation of the crash.

No one can say. Pruss and Lehmann were the finest of airship commanders, men of vast experience. But maybe, I say maybe, when they were landing, a tail wind blew back along the ventilation system. There were always a few leaks of hydrogen. Air blowing from behind would prevent it escaping. Now, when an airship lands it reverses its engines, just as a ship does. And, like a ship, it vibrates. Now I’m not saying this happened, I am saying maybe. But if the Zeppelin vibrates so much, it could break a wire. These bracing wires are thick, and when they snap, heat is generated at the break. Now it the hot end of the wire recoiled into the build-up of leaking gas, this could have caused the fire.