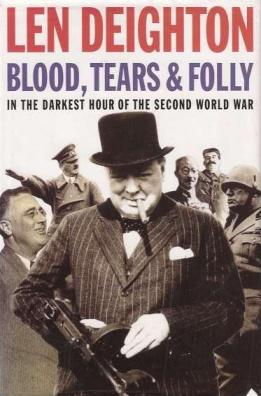

Blood, Tears and Folly

Author: Len Deighton

Release: 1993

Tagline: An Objective Look at World War II

Publisher: Jonathan Cape

Genre: History, Non-Fiction, WWII

ISBN-10: 006017000X

Synopsis: ‘Blood, Tears and Folly’ offers a sweeping and compelling historical analysis of six theatres of war: the Battle of the Atlantic, Hitler’s conquest of western Europe, the war in the Mediterranean, the battle for the skies, Operation Barbarossa and the German assault on Russia, and the entry of Japan into a truly global war.

Declassified by Agent Palmer: Objectivity wins in Deighton’s WW2 analysis, “Blood, Tears and Folly”

Quotes and Lines

I have taken the time, picked the brains and raided the archives of a great number of people while writing this book — so many that I would need another book to give them all proper credit. It is more appropriate to ask forgiveness of all those generous helpers in museums, archives, bookshops, air shows, trains, planes, and cafes who have provided me with ideas, books, photocopies and references galore and now don’t have their names mentioned.

This book, like Fighter and Blitzkrieg before it, would never have seen publication without the late A.J.P. Taylor, who told me that an amateur historian is an historian nevertheless.

Delusions are usually rooted in history and all the harder to get rid of when they are institutionalized and seldom subjected to review. But delusions from the past do not beset the British mind alone. The Germans, the Russians, the Japanese and the Americans all have their myths and try to live up to them, often with tragic consequences.

Newspapers and television did little to counteract the artful management of news at which crooks and tyrants have become adept. Orthodontics and the hair-dryer have become vital to the achievement of political power.

Hans Schmitt, who grew up in Nazi Germany, returned to his homeland as an officer of the American army and become professor of history at the University of Virginia, wrote in his memoirs: ‘Germany had taught me that an uncritical view of the national past generated an equally subservient acceptance of the present.’

In the words of one British major-general who was also an historian:

Mind more than matter, thoughts more than things, and above all imagination, struggle to gain power. New substances appeared, new sources of energy were tapped and new outlooks on life took form. The world was sloughing its skin — mental, moral and physical — a process destined to transform the industrial revolution into a technical civilization. Divorced from civil progress, soldiers could not see this. They could not see that as civilization became more technical, military power must inevitably follow suit: that the next war would be as much a clash between factories and technicians as between armies and generals. With the steady advance of science warfare could not stand still.

The past is a foreign country:

They do things differently there.

L. P. Hartley, the Go-Between

‘War is a series of catastrophes which result in a victory.’ – Georges Clemenceau

Jules Cambon, a French diplomat, saw the drastic decline in fortunes and wrote: ‘France victorious must grow accustomed to being a lesser power than France vanquished.’

He was constantly heckled by the Labour opposition, and he tore into them vehemently and often angrily . . . Churchill knew that he was defending positions which were, in many respects, indefensible. He knew that if the bitterest critics had their way, Chamberlain would resign. He knew that, in that case, he would probably become Prime Minister himself. But throughout the entire political crisis he never spoke or acted except in absolute loyalty to his Prime Minister.

There was no indication that any lessons were learned by the men in London who decided these matters. Little wonder that after the war an official history sardonically quoted Cicero’s maxim: ‘An army is of little value in the field unless there are wise counsels at home.’

The RAF cleaned up and oiled two ancient howitzers, relics from the First World War, which had been used to ornament the lawn outside the depot.

Rommel provides a perfect example of the ‘Peter Principle’ (that a person competent in certain tasks will be promoted to others he is less able to fulfil).

In 1919, led by the French, the signatories of the peace conference signed a Convention of the Regulation of Aerial Navigation. It showed how determined all governments were to control every aspect of aviation. The prospect of ‘freedom of the skies’ terrified Europe, which remained feudal in mentality.

Documents reveal that Hitler’s primary aim at this time was not to help fRanco end the war quickly. Spain’s civil war produced instability so that Western sympathies were sharply divided. Hitler enjoyed the benefits that came from politicians, and commentators, and discord.

This was the arrival of what is now acknowledged as the most amazing intelligence coup of the war: a list of secret German scientific developments that the British referred to as the ‘Oslo Report’.

In the second half of the nineteenth century Britain had been overtaken as an industrial power largely because of social attitudes.

Hitler told his generals that the Russians ‘will think a hurricane has hit them.’ It was necessary to believe this, for otherwise the calculations of the planning staff became sobering. There were insufficient trains, trucks, fuel and ammunition for the five-month campaign that would be needed to destroy the Red Army. In a remarkable feat of self-deception the general staff simply changed their estimates to persuade themselves that they could win in four months, perhaps even one month.

…Hitler liked magic tricks that he thought would dismay his enemies.

But modern battles are not won by tricks, or by good luck either. In the main they are won by supply officers who, thoroughly understanding the operational plan, contrive to have the right ammunition, fuel and food in the right place at the right time.

Both Hitler and Stalin liked to interfere with the day-to-day conduct of battles and to give specific orders about tiny details in the belief that such omnipresence would show them to be superhumanly knowledgeable.

Luftwaffe pilots who contradicted this comfortable conclusion with reports of extensive Red Army movements were ignored.

Only a politician such as Hitler could have remained concerned with indoctrination while on the verge of a military calamity.

The United States, self-sufficient in oil at the time, hoped that a threat of embargo would force Japan to cease its aggressive moves into Asia. It didn’t.

The answer lies in a self-destructive delusion of grandeur.

Both flyers survived and both received medals, but a request for a Medal of Honor for Welch was refused because he had taken off without orders!