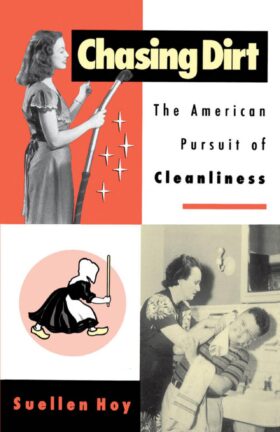

Chasing Dirt

Author: Suellen Hoy

Release: October 10, 1996

Tagline: The American Pursuit of Cleanliness

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Genre: History, United States History, Health, Wellness

ISBN-10: 0195111281

ISBN-13: 978-0195111286

Synopsis: In Chasing Dirt, Suellen Hoy provides a colorful history of this remarkable transformation from “dreadfully dirty” to “cleaner than clean,” ranging from the pre-Civil War era to the 1950s, when American’s obsession with cleanliness reached its peak.

Declassified by Agent Palmer: Suellen Hoy Has All the Dirt on the American Pursuit of Cleanliness

Quotes and Lines

This book is not, however, about plumbing. Instead it is about us as a people, a people who developed and nurtured over a century and a half a love affair with cleanliness. This book is, in fact, the first general history of cleanliness in the United States. No one else has tried to answer what appears to be a simple question: How did Americans become so obsessed with cleanliness when, less than 200 years ago, Europeans found them dreadfully dirty and frequently disgusting?

Americans began to think differently about dirt and to put their faith in prevention over cure as their country urbanized. As long as the United States remained predominantly rural, contagious diseases did not become menacing epidemics. Beginning in the 1820s, however, cities multiplied and expanded, and so did the risks of contagion. Americans who lived in port cities along the eastern seaboard or in the South, for instance, learned from their bouts with cholera that improved personal hygiene and public cleanliness helped combat the disease. As local officials began to enforce sanitary regulations during these epidemics, many discovered that a swept- up environment impeded the spread of cholera.

…at the close of the Civil War only about 5 percent of American houses had running water.

For the majority of Americans who did not have running water in their homes, habits of personal hygiene and housekeeping varied widely. In 1890 only 24 percent of all American homes had running water. And not until the 1930s would the entire urban population have running water, while most of the rural population would not until after 1945. Thus, for a very long time, those who attempted to keep their families and homes reasonably clean found that the means to succeed lagged far behind their good intentions.

At a time when plumbing and heating were largely unavailable to the middle class, Beecher’s recommendations for a clean and comfortable home had obvious limitations. Frequently, when discussing specific house- hold tasks, she encouraged “neatness” and “order” over “cleanliness.” She tended to reserve the word “clean” for descriptions of things that could be made white (that is, clothes, walls, tablecloths) as well as for instructions on the care of the sick and one’s skin. And she never asserted that cleanliness was next to godliness. Instead she offered another “grand maxim”–“A place for every thing, and every thing in its place.”

But Olmsted, who believed slovenliness to be the nation’s “most characteristic” vice, wanted more. He wanted to show these young men from mostly rural areas how to live healthy lives. “If five hundred thousand of our young men could be made to acquire something of the characteristic habits of soldiers in respect to the care of their habitations, their persons, and their clothing, by the training of this war,” he wrote in December 1861, “the good which they would afterwards do as uncon- scious missionaries of a healthful reform throughout the country, would be by no means valueless to the nation.”

For “prominence given to a word gave, of necessity, prominence to an idea.”

New York City sanitarian Stephen Smith, who served as an inspector for the Sanitary Commission, was not alone in testifying to “the wide extent to which the knowledge and principles of Hygiene” had “become popularized in civil as well as military life” during the war. A decade after its end, John Shaw Billings, then assistant surgeon general of the United States Army, contended that “the recent military experiences” had “done more for the cause of Public Hygiene in this country than any other agencies.”

These terribly destructive outbreaks during the 1870s aroused in the whole country an interest in sanitation and hygiene unmatched since the Civil War. Enthusiasm for sanitary reform was always difficult to sustain at the national level. But, outside war, nothing stirred Americans to action more quickly than an epidemic. Thus, in the wake of the yellow fever epidemic of 1878, Congress created a National Board of Health with largely investigatory and advisory responsibilities; it was to assist state and local health officials in devising quarantine regulations and sanitary measures to check the spread of epidemics. Memphis was its first real assignment and test. Residents had concluded that in the face of yellow fever they needed less heroism and more drainage. In response, the National Board of Health sent the colorful and flamboyant sewerage expert Colonel George E. War- ing, Jr., to Memphis in 1879.

1885 ode to “Modern Sanitation”

Our sanitation! Tis the art

Of filling up our homes with drains.

Ah! sewer-gas acts well its part

By conjuring up man’s aches and pains.

The beauteous scarlet fever skips

With typhoid hand in hand.

While sweet Diphtheria gayly trips

O’er stationary washstand.

The cholera doth laugh to see

Its comma bacilli.

Old dysentery’s microbe

Is out upon the fly.

Malaria with its poisonous dart

Lurks ‘neath the water-trap.

Measles upon its round doth start,

Small-pox wakes from its nap.

The crafty plumber makes his bill,

The sewer-gas ascends.

The doctor gives a sugar pill

‘Tis thus we lose our friends.

The undertaker says ’tis well,

The funeral corteges pass.

The letters on the tombstone spell

Hic Jacet, Sewer-Gas.

In 1899, when Mayor Josiah Quincy of Boston declared that “an unclean man could not feel the same sense of self-respect as a clean man” and that “a man was less likely to fall into moral evil if he kept himself physically clean,” he expressed sentiments popular among the new urban middle class.43 Cleanliness was no longer valued solely by an elite; it was accepted by a broad public.

The irony of their perception lay in the fact that the filth theory of disease, while scientifically out- of-date, continued to motivate clean-up efforts that did ameliorate some health problems.

William Sedgwick, public-health bacteriologist of Lawrence, Massachusetts, later wrote, “Before 1880 we knew nothing; after 1890 we knew it all; it was a glorious ten years.”

Harnessing both public spirit and the hope of private gain, the business of cleanliness made personal hygiene an obsession as well as a virtue.

The Model 10 Eureka vacuum cleaner, for example, was advertised as “so revolutionary” and powerful that it “eats up’ dust, sand, grit, lint—any kind of dirt” and “solves every cleaning problem.” Something few servants could do! For good reason, then, the generation of middle-class women who became housewives after 1930 depended more on machines than maids to maintain a decent standard of living for their families.

…most 1950s’ women preferred “the family over work” and found more fulfillment in homemaking tasks than clerical ones. Having grown up during hard times, they associated economic insecurity and hardship with their mothers’ employment. Thus, without a positive image of work and with few good jobs available, they chose domesticity.