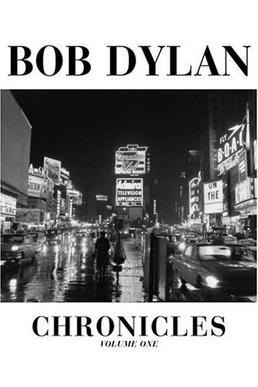

Chronicles: Volume One

Author: Bob Dylan

Release: October 5, 2004

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Genre: Biography, Autobiography, Memoir, Folk Music, Music

ISBN-10: 0743228154

ISBN-13: 978-0743228152

Synopsis: A memoir focussing on his arrival in New York City, the recording of his first album, and subsequent albums New Morning and Oh Mercy.

Declassified by Agent Palmer: Chronicles, Volume One by Bob Dylan is memoir worth your time

Quotes and Lines

Columbia was one of the first and foremost labels in the country and for me to even get my foot in the door was serious. For starters, folk music was considered junky, second rate and only released on small labels. Big time record companies were strictly for the elite, for music that was sanitized and pasteurized.

At last I was here, in New York City, a city like a web too intricate to understand and I wasn’t going to try.

Actually, I wanted to play for anybody. I could never sit in a room and just play all by myself. I needed to play for people and all the time. You can say I practiced in public and my whole life was becoming what I practiced.

One singer I crossed paths with a lot, Richie Havens, always had a nice-looking girl with him who passed the had and I noticed that he always did well. Sometimes she passed two hats. If you didn’t have some kind of trick, you’d come off with an invisible presence, which isn’t good.

Most of the other performers tried to put themselves across, rather than the song, but I didn’t care about doing that. With me, it was about putting the song across.

…happiness isn’t on the road to anything. That happiness is the road.

Outside of Mills Tavern the thermometer was creeping up to about ten below. My breath froze in the air, but I didn’t feel the cold. I was heading for the fantastic lights. No doubt about it. Could it be that I was being deceived? Not likely. I don’t think I had enough imagination to be deceived; had no false hope, either. I’d come from a long ways off and had started from a long ways down. But now destiny was about to manifest itself. I felt like it was looking right at me and nobody else.

The air was bitter cold, always below zero, but the fire in my mind was never out, like a wind vane that was constantly spinning.

Folk songs transcended the immediate culture.

I’d always pictured myself dying in some heroic battle rather than in bed.

There was a lot of halting and waiting, little acknowledgment, little affirmation, but sometimes all it takes is a wink or a nod from some unexpected place to vary the tedium of a baffling existence.

Sometimes that’s all it takes, the kind of recognition that comes when you’re doing the thing for the thing’s sake and you’re on to something–it’s just that nobody recognizes it yet.

It was beginning to dawn on me that I would have to learn how to play and sing by myself and not depend on a band until the time I could afford to pay and keep one.

What was the future? The future was a solid wall, not promising, not threatening–all bunk. No guarantees of anything, not even the guarantee that life isn’t one big joke.

Picasso had fractured the art world and cracked it wide open. He was revolutionary. I wanted to be like that.

…it dawned on me that I might have to change my inner thought process . . . that I would have to start believing in possibilities that I wouldn’t have allowed before, that I had been closing my creativity down to a very narrow, controllable scale . . . that things had become too familiar and I might have to disorientate myself.

Everything was always new, always changing. It was never the same old crowd upon the streets.

I had a wife and children whom I loved more than anything else in the world. I was trying to provide for them, keep them out of trouble, but the big bugs in the press kept promoting me as the mouthpiece, spokesman, or even conscience of a generation. That was funny. All I’d ever done was sing songs that were dead straight and expressed powerful new realities. I had very little in common with and knew even less about a generation that I was supposed to be the voice of.

After a while you learn that privacy is something that you can sell, but you can’t buy it back.

Woodstock had turned into a nightmare, a place of chaos. Now it was time to scramble out of there in search of some new silver lining and that’s what we did.

Wherever I am, I’m a 60’s troubadour, a folk-rock relic, a wordsmith from by gone days, a fictitious head of state from a place nobody knows. I’m in the bottomless pit of cultural oblivion. You name it. I can’t shake it.

If you have to lie, you should do it quickly and as well as you can.

I figured it would take me at least three years to get to the beginning, to find the right audience, or for the right audience to find me. The reason I thought it would take three years was that after the first year a lot of the older people wouldn’t be coming back, but younger fans would bring their friends the second year so attendance would be just about equal. And in the third year, those people would also bring their friends and it would form the nucleus of my future audience.

Some people seem to fade away but then when they are truly gone, it’s like they didn’t fade away at all.

Sometimes you just have to bite your upper lip and put sunglasses on.

Northerns think abstract. When it’s cold, you don’t fret because you know it’s going to be warm again . . . and when it’s warm, you don’t worry about that either because you know it’ll be cold eventually. It’s not like in the hot places where the weather is always the same and you don’t expect anything to change.

The concept of being morally right or morally wrong seems to be wired to the wrong frequency. If someone steals leather and then makes shoes for the poor, it might be a moral act, but it’s not legally right, so it’s wrong. That stuff troubled me, the legal and moral aspect of things. There are good deeds and bad deeds. A good person can do a bad thing and a bad person can do a good thing.

Sometimes the things that you liked the best and that have meant the most to you are the things that meant nothing at all to you when you first heard or saw them.

My father had his own way of looking at things. To him life was hard work. He’d come from a generation of different values, heroes and music, and wasn’t so sure that the truth would set anybody free. He was pragmatic and always had a word of cryptic advice. “Remember, Robert, in life anything can happen. Even if you don’t have all the things you want, be grateful for the things you don’t have that you don’t want.”

Folk music was a reality of a more brilliant dimension. It exceeded all human understanding, and if it called out to you, you could disappear and be sucked into it. I felt right at home in this mythical realm made up not with individuals so much as archetypes, vividly drawn archetypes of humanity, metaphysical in shape, each rugged soul filled with natural knowing and inner wisdom. Each demanding a degree of respect. I could believe in the full spectrum of it and sing about it. It was so real, so more true to life than life itself. It was life magnified. Folk music was all I needed to exist. Trouble was, there wasn’t enough of it.

First thing I did was go trade in my electric guitar, which would have been useless to me, for a double-o Martin acoustic.

Who is he? He’s a hustling ex-sign painter from Oklahoma, an antimaterialist who grew up in the Depression and Dust Bowl days–migrated West, had a tragic childhood, a lot of fire in his life–figuratively and literally. He’s a singing cowboy, but he’s more than a singing cowboy. Woody’s got a fierce poetic soul–the poet of hard crust sod and gumbo mud.

I said to myself I was going to be Guthrie’s greatest disciple. It seemed like a worthy thing. I even seemed to be related to him.

One thing for sure, Woody Guthrie had never seen nor heard of me, but it felt like he was saying, “I’ll be going away, but I’m leaving this job in your hands. I know I can count on you.”

The road ahead had always been encumbered with shadowy forms that had to be dealt with in one way or another.