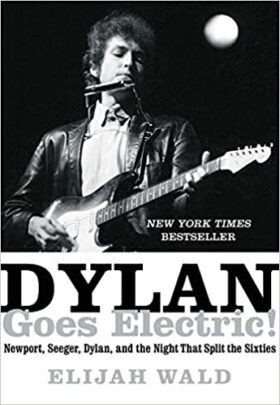

Dylan Goes Electric!

Author: Elijah Wald

Release: July 14, 2015

Tagline: Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties

Publisher: Dey Street Books

Genre: History, Music, Folk Music, Rock Music

ISBN-10: 0062366688

ISBN-13: 978-0062366689

Synopsis: On the evening of July 25, 1965, Bob Dylan took the stage at the Newport Folk Festival. Backed by an electric band, he roared into a blistering version of “Maggie’s Farm,” followed by his new rock single, “Like a Rolling Stone.” The audience of committed folk purists and political activists who had hailed him as their acoustic prophet reacted with a mix of shock, boos, and scattered cheers. It was the shot heard round the world—Dylan’s declaration of musical independence, the end of the folk revival, and the birth of rock as the voice of a generation—and one of the defining moments in twentieth-century music.

Declassified by Agent Palmer: If you enjoy Context and Details: Dylan Goes Electric is the book for you

Quotes and Lines

What happened next is obscured by a maelstrom of conflicting impressions: The New York Times reported that Dylan “was roundly booed by folk-song purists, who considered this innovation the worst sort of heresy.” In some stories Pete Seeger, the gentle giant of the folk scene, tried to cut the sound cables with an axe. Some people were dancing, some were crying, many were dismayed and angry, many were cheering, many were overwhelmed by the ferocious shock of the music or astounded by the negative reactions.

In 1965 Dylan was only twenty-four years old, but he had already gone through a lot of changes and been criticized and attacked for each of them. His first performances as a teenage rock ‘n’ roller were met with laughter and jeers. When he turned to folk music, the high school girlfriend who had shared his early passions was troubled, asking why he’d given up “the hard blues stuff.” When he turned from singing traditional folk songs to writing his own material, old supporters accused him of becoming “melodramatic and maudlin”–one, stumbling across a typescript of “The Times They Are a-Changin,” demanded, “What is this shit?” When he turned from sharp topical lyrics to introspective poetic explorations, followers who had hailed him as the voice of a generation lamented that he was abandoning his true path and “wasting our precious time.” When he added an electric band, he was booed around the world by anguished devotees, one famously shouting “Judas!”

He valued folk music as something ordinary people played for themselves and their neighbors in their communities: his notes to Folk Songs of Four Continents, one of four albums he made in 1955 with the Song Swappers, described the group as “purposely composed of ‘average’ voices, of limited range and little training,” with the aim of “encouraging group singing among lovers of folk music, amateur and professional.”

To some extent that meant they had different relationships to the music: for Seeger it was inextricable from communities that created it and the historical processes that shaped those communities, while for Dylan it was a private world of the imagination.

Anyone hoping to understand the cultural upheavals of the 1960s has to recognize the speed with which antiestablishment, avant-garde, and grass-roots movements were coopted, cloned, and packaged into sealable products and how unexpected, confusing, and threatening that was for people who were sincerely trying to find new ways to understand the world or to make it a better place.

When critics attacked the Kingston Trio, the Brothers Four, or the New Christy Minstrels for having ordinary voices and instrumental skills and relying on a small repertoire of familiar songs, they were highlighting exactly what made those groups attractive to millions of kids across the United States: the idea that anyone could be part of the movement, not only as a spectator but as a participant.

…a glowing encomium from Broadside’s Sis Cunningham to the new generation of songwriters, “Woody’s children,” led by “Bob Dylan, only 22, whose songs in a few short months have gone around the country and overseas.”

Recalling a trip to Albany, Georgia, Seeger echoed Landron’s misgivings: “the black people in Albany had their own music. Why’d they need some Yankee to come down and sing to them?” But he also described a funny but significant interchange during his performance: a woman leaned over to Cordell Reagon of the Freedom Singers and said, “If this is white folks’ music, I don’t think much of it,” and Reagon responded, “Hush, if we expect them to understand us, I’ve got to try to understand them.”

“It was quite ludicrous,” she recalls, “but that’s how we were then. You would ask your date, ‘Do you know Genet? Have you read À rebours?’ And if he said yes, you fucked him.”

In Faithfull’s memory, “the zeitgeist streamed through him like electricity. He was my Existential hero, the gangling Rimbaud of rock . . . wearing Phil Spector shades and an aureole of hair and seething irony.”

Jagger recalled Dylan telling Keith Richards, “I could have written ‘Satisfaction’ but you couldn’t have written ‘Tambourine Man,’” and when the interviewer seemed shocked, he added, “That was just funny. It was great. . . . It’s true.”

They recognized Dylan’s Sunday night set, when he “electrified one half of his audience and electrocuted the other,” as the “journalistic happening” of the 1965 Newport Festival.

As a student from New York explained, “You listen to people like Son House and you’re out in this grass and everything and you almost think you’re back in the places where these people live and then some seagull starts yelling, or a jet goes by, or a whistle blows from Newport and it makes you realize that they are here and you’re not there.”

What anyone experienced depended not only on what they thought about Dylan, folk music, rock ‘n’ roll, celebrity, selling out, tradition, or purity, but on where they happened to be sitting and who happened to be near them, and in the end the disputes and conflicting memories may count for more than the evidence preserved on tape and film–some of which must also be taken with a grain of salt, since film clips were edited to heighten the drama of the moment, splicing in the clamorous crowd noise from the beginning or end of Dylan’s set to augment the relatively low-key response captured by the stage microphones after that first song.

Seeger concluded, “Maybe Bob Dylan will be like Piocasso, surprising us every few years with a new period. I hope he lives as long. I don’t think there’s another songwriter around who can touch him for a certain independent originality, even though he is part of a tradition.” (In 1967 after Dylan’s album John Wesley Harding was released)

For Seeger, that was the crux of the matter: on the one hand, the importance of artists creating personal, meaningful work; on the other, the importance of community and tradition.

Dylan’s reception at Newport had so much resonance because he mattered to his audience in a way pop music had never mattered before, and the power of that message came not only from Dylan but from Newport, from the fact that he was booed at a beloved and respected musical gathering, by an audience of serious, committed young adults. The fans who booed him from Forest Hills to the Manchester Free Trade Hall over the next year were showing not only their anger at his capitulation to the mainstream but their solidarity with that first mythically angered cohort of true believers.

But it continues to resonate because, if its details are emblematic of a particular moment, the central conflict was timeless. It was not the death of an old dream and the birth of a new, but the clash of two dreams, both very old and both very much still with us. They are the twin ideals of the modern era: the democratic, communitarian ideal of a society of equals working together for the common good and the romantic, libertarian ideal of the free individual, unburdened by the constraints of rules or custom. At Newport that night, Seeger was standing up for one ideal and Dylan for the other, and many people felt forced to choose sides, and for a while the verdict of history seemed to be that Dylan was right and Seeger was wrong.

Fifty years later it doesn’t look that simple.