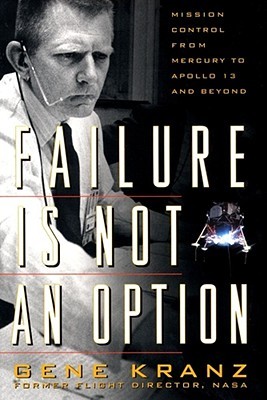

Failure is Not an Option

Author: Gene Kranz

Release: April 12, 2000

Tagline: Mission Control from Mercury to Apollo 13 and Beyond

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Genre: Biography, Science, Space, Technology, History

ISBN-10: 0743200799

ISBN-13: 978-0743200790

Declassified by Agent Palmer: Kranz’s Failure is Not an Option is a Great Look Back and a Kick in the Pants To Get Going Again

Quotes and Lines

Mercury worked because of the raw courage of a handful of men like [Gordo] Cooper, who sat in heavy metal eggcups jammed on the top of rockets, and trusted those of us on the ground. That trust tied the entire team into a common effort.

I had left behind a world where airplanes were flying at roughly five miles a minute. In this new, virtually uncharted world we would be moving at five miles per second.

A launch is an existential moment, much like combat. With no time to think about anything, you had to be prepared to respond to any contingency–and those contingencies had to be as fully anticipated as possible before you pushed the button.

The tools we used in Mercury were primitive, but the dedication of highly trained people offset the limitations of the equipment available to us in these early days and kept the very real risks under control. But at a price; this was high-sweat, high-risk activity, demanding a degree of coordination between the ground and the capsule exceeding what I had experienced even in the testing of experimental aircraft.

…having the experience to anticipate what could happen rather than just reacting to what was happening at the moment.

I had sat next to Chris Kraft since the first mission and was amazed at his aplomb now that he finally had an American in orbit. High-risk leadership beckons many, but few accept the call.

…learning by doing was the only way a controller could ever become smart enough to succeed in the tough and unforgiving environment of spaceflight operations.

We felt like standing and cheering, but that didn’t happen in Kraft’s control room, only in the movies.

The nature of our work made us develop strong loyalties to each other. Most of us were in our late twenties and early thirties. Outside of wartime, I do not believe that young people had ever been given responsibilities so heavy or historic. We were in jobs that appealed to the adventurer, dreamer, and Foreign Legionnaire in each of us.

Cooper, the loner and rebel against the spaceflight bureaucracy, had pulled off a great mission and a picture-perfect entry.

“You will never remember the many times the launch slipped, but the on-time failures are with you always.” – Walt Williams

My high school thesis was entitled, “The Design and Possibilities of the Interplanetary Rocket.”

Writing in 1950, I made this forecast:

An examination of the current technical and industrial development demonstrates the high probability that the Moon will shortly be conquered by man. The base will probably be established in five years and completed in ten.

Those in the Space Task Group were a rainbow of personalities, mannerisms, and speech.

When the Avro Arrow, the world’s top performing interceptor aircraft, was canceled by the Canadian government, the engineers came south to the United States and into the Space Task Group, providing much of the instant maturity and leadership needed for Mercury.

Living as we did in an environment that combined the temperament of a football training camp and the confinement of a submarine, with ego and pride all around, as well as relentless pressure, I sometimes wondered why an occasional bloody brawl didn’t break out.

During the mission, no one called me Kranz; I now answered to the name of “Flight.”

Stale cigarette butts, cold coffee, and day-old pizza made up the scent of Mission Control.

Treating docked spacecraft as a single system was one of the most important lessons to come from Gemini. It had a profound effect on our future success as flight controllers. The lesson learned on Gemini 8 would be invaluable on Apollo 13.

My credo: always hire people who are smarter and better than you are and learn with them.

Technology and training were pushing us to the ultimate standard: failure was not an option. In simulations and in real time controllers knew that if the team made the right decisions, we would accomplish the mission and bring ou men home safely. If we were wrong in real time, we would ruin the mission and the crew might be killed.

Knowing what we didn’t know was how we kept people from getting killed.

We were blessed with a dedicated, well-informed, and highly professional press corps in the 1960s. (Unlike so many “reporters” today, they knew the difference between objective reporting of news and hyping things up to entertain the audience–and bump up their ratings.)

Wrapping up the press briefing, I said, “The nature of flight test is working at the boundaries of knowledge, experience, and performance and taking the risks needed to get there. There are times where the things you learn are things that you don’t expect. Often the plan you execute is different than the one you started. I believe this is one of those times.”

I realized how narrow my world had become because of the intensity and isolation of my work over the last seven years. I had never been on a West Coast campus. What I saw was beyond my belief, the TV headlines coming alive. It was my first live encounter with the hippie generation.

Even the space program was picketed and bomb threats were reported. Everything we carried into the Mission Control Center was inspected. Security guards roamed our parking lots during missions. We practiced bomb threat evacuations from Mission Control, always leaving a mall team to hold the fort if we had a crew aloft. These events provided a violent background to our final charge to reach the Moon. Fortunately, the public’s support for the lunar program remained high. Apollo was a bright glow of promise in a dark and anxious era.

Missions are tough on kidneys and bladders.

Through trust you reach a place where you can exploit opportunities, respond to failures, and make every second count. As gigantic as the machine was, and as puny as we humans were measured against its towering bulk, the human factors balanced technology on the scale. It would be this balance that would be, indeed had to be, maintained successfully throughout manned spaceflight operations.

He [Sam Phillips] indicated a willingness to push launch into August if we needed more training time.

I have the same feeling every time I walk into the MCC. It is a place where history is being made, day by day. It is the home base, the control center for our explorers.

Okay, all flight controllers, listen up.

Today is our day, and the hopes and the dreams of the entire world are with us. This is our time and our place, and we will remember this day and what we will do here always.

In the next hour we will do something that has never been done before. We will land an American on the Moon. The risks are high . . . that is the nature of our work.

We worked long hours and had some tough times but we have mastered our work. Now we are going to make this work pay off.

You are a hell of a good team. One that I feel privileged to lead.

Whatever happens. I will stand behind every call that you will make.

Good luck and God bless us today!

…I have put down my best recollection of what I said.

We have just landed on the Moon. In a way, I feel cheated that I didn’t have the chance to savor those seconds as deeply as those who watched.

“Let’s solve the problem, team . . . let’s not make it any worse by guessing.”

“My message to everyone is: rely on your own judgement, update your data as you go along. If you are not the right person, step aside and send me someone who is. When you leave this room you will pass no uncertainty to our people. They must become believers if we are to succeed.”

“The United States was not built by those who waited and rested and wished to look behind them. This country was conquered by those who moved forward, and so will space.” – President Kennedy

“We fought and won the race in space and listened to the cries of the Apollo 1 crew. With great resolve and personal anger, we picked up the pieces, pounded them together, and went on the attack again. We were the ones in the trenches of space and with only the tools of leadership, trust, and teamwork, we contained the risks and made the conquest of space possible.” – Kranz

The concluding words were the bitter wine: “This may be the last time in this century that men will walk on the Moon!” We had started out with John Kennedy’s vision and command: get a man on the Moon by the end of the decade. Nixon’s message was, effectively, Apollo’s obituary.

Entering the twenty-first century, we have an unimaginable array of technology and a generation of young Americans schooled in these technologies. With our powerful economy, we can do anything we set our mind to do. Yet we stand with our feet firmly planted on the ground when we could be exploring the universe.

Three decades ago, in a top story of the century, Americans placed six flags on the Moon. Today we no longer try for new and bold space achievements; instead we celebrate the anniversaries of the past.

The last set of clear goals for space was produced in 1986 by a national commission that included Neil Armstrong, Chuck Yeager, Gerard O’Neill (CEO, Geostar Corporation), Jeane Kirkpatrick (former U.S. ambassador to the U.N.), Thomas Paine (former NASA Administrator), and many others. The report, entitled Pioneering the Space Frontier, was developed through a series of fifteen public forums held across the country and represented the opinions of a substantial portion of the public on the future of the civilian space program. The goals defined in 1986 are as good today as they were a decade and a half ago. We do not need to engage in another round of studies. We must establish a plan to meet the goals of the National Commission on Space.

This book began with the dream given to my generation, but I believe that President John F. Kennedy was addressing all generations to come when he said:

The United States was not built by those who waited and rested and wished to look behind them. This country was conquered by those who moved forward, and so will space. . . .

Well, space is there and we are going to climb it, and the Moon and the planets are there. And as we set sail we ask God’s blessing on the most hazardous and dangerous and greatest adventure on which man has ever embarked.

My wish as I close this book is that one day soon, a new generation of Americans will find the national leadership, the spirit, and the courage to go boldly forward and complete what we started.

The NASA history series, particularly the books This New Ocean (Project Mercury), On the Shoulders of Titans (Project Gemini), Chariots of Apollo (Project Apollo), and Stages of Saturn (Saturn rocket development), were invaluable references in developing the chronology in the book. I recommend them to my readers.