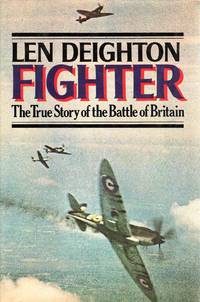

Fighter

Author: Len Deighton

Release: May 12, 1978

Tagline: The True Story of The Battle of Britain

Publisher: Alfred A. Knopf

Genre: History, Military, World War II

ISBN-10: 0394427572

ISBN-13: 978-0394427577

Synopsis: An analysis of the aerial battle between the Royal Air Force and the Luftwaffe in the summer of 1940 provides a full account of the tactics and artillery on both sides, including descriptions of the Hurricane, Spitfire, and Bf 109 aircraft.

Declassified by Agent Palmer: A Book Report on “Fighter: The True Story of the Battle of Britain” by Len Deighton

Quotes and Lines

The key to the story is that the air commanders before the Second World War had very little previous experience to draw on. The materials and methods of war are of course constantly changing. Generals acquire rifles, machine guns, and tanks. Admirals acquire bigger battleships and submarines. But they have some idea from earlier wars of the problems that are likely to face them. The air commanders had no such resource. The war in the air of the First World War had been largely a matter of dog-fights between individual aircraft. The few bombing raids had caused terror and little effective damage. Those who determined air strategy after the war had to proceed by dogma alone, a dogma that was little more than guesswork.

Churchill honoured the fighter pilots with the immortal phrase, “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.”

On 25 November Dowding was relieved of his command and passed into oblivion. Yet, “he was the only man who ever won a major fighter battle or ever will win one.”

In the last resort battles are decided by the men and machines that take part in them. I am afraid that many of us who write about war neglect this side of it and write in great sweeping terms. Len Deighton does not.

History is swamped by patriotic myths about the summer of 1940.

Petty jealousies and vicious vendettas flourished as empires were built.

And so Goring’s so—called Eagle Attack (Adlerangriff) was born in the same bungling, buck-passing muddle that had left Guderian at Sedan without objectives, and then halted him while the men in ‘Berlin thought about it. It was the same mess of contradictory orders that had Stepped the German armour at Dunkirk. The top brass of the Wehrmacht were learning that it was safer to equivocate. “Sea-lion was contemplated, said the jokers afterwards “but never planned.”

Like many high ranking airmen, and manufacturers of bombing aircraft, Goring subscribed to the theories of General Giulio Douhet, an Italian who believed that armies and navies were best employed as defensive forces while bomber fleets conquered the enemy. Just before he died in 1930, General Douhet wrote a futuristic story called “The War of 19–.” Often quoted but seldom read, Douhet’s words had such profound effects upon the German and RAF High Commands that they are worth examining. Written in the documentary manner of H. G. Wells, Douhet’s story described how an “Independent German Air Force” fought great aerial battles against the Belgian and French air units. “There was no doubt that the enemy’s purpose was to make the mobilisation and concentration of the Allied armies as difficult as possible,” said Douhet’s imaginative fiction. The Allies replied with “night-bombing brigades” that attacked German cities with explosives, incendiaries, and poison gas.

Douhet smoothly concluded that “No one can command his own sky if he does not command his adversary’s sky.”

“A difficult man, a self-opinionated man, a most determined man, and a man who knew, more than anybody, about all aspects of aerial warfare.” – General Sir Frederick Pile, G.C.B., D.S.O., M.C. (General Officer Commander in Chief Anti-Aircraft Command, 1939-45), of Dowding

But Dowding was no paragon. Too often he resorted to caustic comments when a kind word of advice would have produced the same, or better, results.

Said one of them, “Auxiliaries are gentlemen trying to be officers, Regulars are officers trying to be gentlemen, VRs are neither trying to be both.”

And while these great battles raged across the tables of the Operations Rooms, the Sector Controllers spoke with their fighter pilots 20,000 feet above. They watched the counters converge and heard the pilots as they wheeled and fired and cursed and died. Never before had there been battles like these.

“Take the piston rings out of my kidneys,

The connecting rods out of my brain,

Take the cam-shaft from out of my back-bone,

And assemble the engine again.”

-Traditional Airman’s Song

The history of invention often shows a pattern of acceleration, in the later stages of which inventors take if for granted that some other element they need will miraculously appear. This is particularly true of inventions applicable to warfare, stimulated as they often are by politics, economics, or predicament.

It has been written, many times, that the Spitfire was a privately developed machine that impressed the Air Ministry so deeply that they wrote a specification to fit it. This is not true. The true story is less dramatic and more complex.

It was an inspired achievement, for only long after Mitchell’s death, as speeds went up and up, did research show how far ahead of its time Mitchell’s wing design had been.

Watson-Watt added a final paragraph on the subject of detection. He wrote:

Meanwhile attention is being turned to the still difficult but less unpromising problem of radio-detection as opposed to radio-destruction, and numerical considerations on the method of detection by reflected radio waves will be submitted if required.

In May 1940, an anti-aircraft battery at Essen-Frintrop used a Würzburg radar, and was able to shoot down an RAF bomber which they could not see.

There had never before been a battle in three dimensions, and never a battle moving as such speeds. Yet, for most of the fighting, the coloured counters on the plotting table were no more than four minutes-about fifteen miles-behind events. It proved good enough.

The low importance given to the Luftwaffe fighter arm contributed to the German failure in 1940.

But while all bureaucracy is devious, military bureaucracy is conspiratorial.

“The odds were great; our margins small; the stakes infinite.” – Winston S. Churchill

PHASE ONE Starting in July there was a month of attacks on British coastal convoys and air battles over the Channel: Kanalkampf.

PHASE TWO From 12 August-the eve of Adlertag (Eagle Day)–came the major assault. Goring and Nazi propaganda writers called it Alderangriff (Eagle Attack). It continued for just over a week.

PHASE THREE What the RAF called “the critical period,” in which RAF fighter airfields in south-east England were priority objectives. This lasted from 24 August until 6 September.

PHASE FOUR From 7 September. The attacks centred on London, first by daylight and then by night.

The RAF fighter pilots——like the Regular officers that so many of them were——had tried to adapt the tight vee formations of peacetime to the needs of war. But tight formations require all of a man’s concentration and leave no spare moments for looking round. The modern high—speed monoplanes were more complex than the biplanes and, apart from watching the sky for enemy aircraft, pilots needed to attend to their instruments. And in tight formations, each aircraft blocks a large sector of his neighbour’s sky. Adding a “tail-end Charlie” to weave from side to side at the rear of the formation, and thus protect the tail, had resulted in the loss of too many tail-end Charlies. By the middle of July, weavers were seldom seen.

The controversial Lord Beaverbrook ran his Ministry as he ran his newspapers. Over his desk there was displayed the notice “Organisation is the enemy of improvisation.”

“Better a stringency in spares and a bountiful supply of aircraft than a surplus of spares and a shortage of aircraft,” explained Beaverbrook.

…as Beaverbrook reasoned, “industry is like theology. If you know the rudiments of one faith you can grasp the meaning of another.”

Behind the fighter-bombers–Jabos–there were eighteen Dornier Do 17s of KG2. Like the Junker Ju 88s of the Portsmouth attack, these bombers were led by their Geschwaderkommodore. In the case of the Helzhammer, this was the Kanalkampfjührer himself: Oberst Fink.

Meanwhile they photographed each other patting pet dogs, playing cards, and relaxing in deck chairs on neatly trimmed grass. In 1940 there was honey still for tea, in the world’s last romantic battle.

This gave the Bf 109 a mere nine seconds of gunfire compared with the RAF’s machine guns which could deliver fourteen seconds of fire. And such gunfire could be equally destructive if the pilot flew very close.

“The Reichsmarschall never forgave us for not having conquered England.” – Oberst Karl Koller, Staff Officer and later Göring’s Chief of Staff.

The tactics of the air war–as they emerged–were not very much different from the lessons that had been learned in 1914 to 1918. Height was still the trump card, with attacks out of the sun the most reliable tactic. Heavier fighters, that accelerated more quickly into the dive, were often forgiven other faults. Acceleration in level flight is a quality not listed in any aircraft specification, but for a pilot coming under fire, it often meant the difference between life and death.

The 25-year-old Wick was highly regarded by the lower ranks in the fighter force for his readiness to answer back to the top brass. When Wick’s unit was paraded for a visit by Feldmarschall Sperrle, Wick was gently told that his ground crews were unmilitary in appearance. Wick asked his Air Fleet commander innocently if he didn’t think that refuelling, rearming, and servicing the fighters, to maximise operational status, wasn’t more important than getting a haircut.

In 1940 the Bf 109 averaged about 90 minutes’ flying time. But climbing and getting into formation, as well as finding airfields on the return, meant that German fighters never had more than about 30 minutes over English soil.