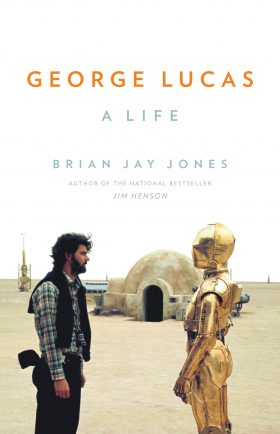

George Lucas: A Life

Author: Brian Jay Jones

Release: December 6, 2016

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Genre: Biography, Performing Arts, Movies, Entertainment, Innovation, History

ISBN-10: 0316257443

ISBN-13: 978-0316257442

Main Character: George Lucas

Declassified by Agent Palmer: The Underappreciated Innovator: A Review of George Lucas: A Life by Brian Jay Jones

Quotes and Lines

Lucas vowed he’d never cede control over his films to executives at the studios again. What did they know about filmmaking? “They tell people what to do without reason,” Lucas complained. “Sooner or later, they decided they know more about making movies than directors. Studio heads. You can’t fight them because they’ve got the money.”

“I was not a bad student; I was an average student,” Lucas explained. “I was a C, sometimes C-minus student. I was definitely not an achiever.” That was putting it mildly; by the end of his freshman year, he was getting Ds in science and English. “I daydreamed a lot,” Lucas said later. “I was never described as not a bright student. I was always described as somebody who could be doing a lot better than I was doing, not working up to potential. I was so bored.”

“I’d be working all day, all night, living on chocolate bars and coffee,” said Lucas. “It was a great life.”

Marcia put it a bit more elegantly, noting that “we want to complete ourselves, so we look for someone who is strong where we’re weak.”

“An assistant with an opinion, nothing more dangerous than that, right?” – Spielberg

It was “the importance of self and being able to step out of whatever you’re in and move forward rather than being stuck in your little rut,” Lucas explained in 1971. “People would give anything to quit their jobs. All they have to do is do it…. They’re people in cages with open doors.”

For Lucas, it was more than unjust; it was immoral. “The terrible thing about this country is that the dollar is valued above the individual,” said Lucas. “You can buy another person no matter how talented he is and then tell him he’s wrong. They do not like to trust people.” Lucas wouldn’t trust studios again. Ever.

“We were the movie brats who go together a long time ago and decided to talk about how hard it is to make movies,” said Spielberg. “I mean, we’re constant complainers. We love complaining to each other.”

“You couldn’t pay me enough money to go through what you have to go through to make a movie,” he complained to the New York Times. “ It’s excruciating. It’s horrible. You get physically sick. I get a very bad cough and a cold whenever I direct. I don’t know whether it’s psychosomatic or not. You feel terrible. There is an immense amount of pressure, and emotional pain…. But I do it anyway, and I really love to do it. It’s like climbing a mountain.”

“You go crazy writing,” Lucas said later. “You get psychotic. You get yourself so psyched up and go in such stranger directions in your mind that it’s a wonder that all writers aren’t put away someplace.”

“I thought, ‘we all know what a terrible mess we have made of the world,’” said Lucas. We also know, as every movie made in the last ten years points out, how terrible we are, how we have ruined the world and what schmucks we are and how rotten everything is. And I said, what we really need is something more positive.”

For Lucas, the idea of The Star Wars offered a different, even higher calling.

“How many people think the solution to gaining quality control, improving fiscal responsibility, and stimulating technological innovation is to start their own special-effects company?” Ron Howard said admiringly. “But that’s what he did.”

It would be Williams, perhaps more than any other collaborator, who would give Star Wars the air of excitement and dignity that Lucas envisioned–and his score would become iconic, its opening brass blare cheered by audiences through seven movies and counting.

“If I left anything for a day,” he feared, “it would fall apart, and it’s purely because I set it up that way and there is nothing I can do about it,” Lucas said. “It wasn’t set up so I could walk away from it. Whenever there is a leak in the dam, I have to stick my finger in it.”

“Intimate that a rewarding, good life is within one’s reach despite adversity,” Lucas jotted in his notes, “ but only if one does not shy away from the hazardous struggles without which one can never achieve true identity.”

“Success…is a very difficult emotional experience to go through,” he said.

While writing the story, Lucas had envisioned Indy’s father as “more of a professor…[a] Laurence Olivier type, an Obi-Wan Kenobi type.” But Spielberg had something different in mind. Indiana Jones had been spawned partly by Spielberg’s thwarted desire to direct a James Bond film–so in a way, that made James Bond the father of Indiana Jones. It only made sense to Spielberg, then, that Sean Connery,–the first, and to his mind best, James Bond–should play Indy’s father, Henry.

There was also just a touch of fatalism involved as well. “It took a long time for me to adjust to Star Wars,” confessed Lucas. “I finally did, and I’m going back to it. Star Wars is my destiny.”

“I want people to like what I do. Everybody wants to be accepted at least by somebody,” he insisted. “But we live in a world now where you’re forced to become part of this larger corporate entity called media…”

“I’m a cynical optimist,” he told Time magazine, laughing. “I’m a cynic who has hope for the human race.”

“I’ve never been that much of a money guy,” Lucas told Businessweek. “I’m more of a film guy, and most of the money I’ve made is in defense of trying to keep creative control of my movies.”

“I hope I’ll be remembered as one of the pioneers of digital cinema. In the long run, that’s probably all it will come down to.” Then, with a twinkle, he added, “They might remember me as the maker of some of those esoteric twentieth-century science fiction movies.”

“I can’t help feeling that George Lucas has never been fully appreciated by the industry for his remarkable innovations,” said director Peter Jackson. “He is the Thomas Edison of the modern film industry.”