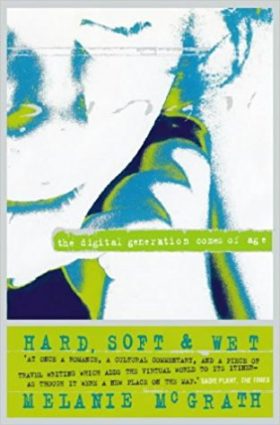

Hard, Soft & Wet

Author: Melanie McGrath

Release: 1997

Tagline: The Digital Generation Comes of Age

Publisher: Harper Collins

Genre: Fiction, Technology

ISBN-10: 0002555867

ISBN-13: 978-0002555869

Synopsis: One woman’s search for tomorrow as the digital generation emerges in the mid-1990’s.

Declassified by Agent Palmer: Hunting Down the Future in 1997: A Review of Hard, Soft and Wet by Melanie McGrath

Quotes and Lines

There’s no explaining why Nancy and I have stayed friends over the years. We don’t have much in common any more. Not much you could put your finger on. But friends we are, strung together by our few similarities and by the thin, tough mesh of our small shared past.

I was seventeen and everything was ripe with meaning.

Our friendship isn’t based on long shared experience, but on some intangible, timeless affection.

We don’t have to know much about the everyday run of one another’s lives, to love one another all the same.

‘The America of the first frontier.’ She flips an insect from her arm. ‘Northern California is the one place where the old and new frontiers collide. It’s at the epicentre of every dream America ever had. The old frontier,’ she waves at the trees, at the key of light through the leaves, ‘and the new frontier a few miles down the road in Silicon Valley. The high-tech frontier of chips and virtual worlds.’

I spent much of the weekend taking my first frail steps along the technological frontier in Internet Relay Chat.

She sat on the bed, looked about her at the library of books and began to wonder in a wistful tone whether we were just part of some transitional generation, unconvinced by the old myths but incapable of absorbing the new ones either, condemned to cling on to a fifties B-movie future of personal commuter jet-pods, clingy silver suits and robot pets which we knew to be fake.

I would hunt down the future, starting with the everyday intimations of tomorrow — the games, gadgets and consumer fads — that were already an invisible part of so many young lives and I would work my way up to the networks, which will, in their turn, become a mundane part of the lives of those children’s children, and perhaps also of my own children.

‘The two most unpredictable things in this world are weather and women,’ the man says turning away.

‘Sweetie, education and technology are the ways the future gets made,’ she says.

I’ve got nothing much against the suburbs anyway. They appear bland, but that’s just surface skim. Underneath, they’re the same heaving mess of calamities and cock-ups as everywhere else.

‘I always think the weirdest thing about Battletech and all those geeky games,’ she follows, changing the subject, ‘is the mountain of trivia you have to absorb to make any sense out of it at all. It’s such a boy thing. Lists and specs and reams of completely pointless detail.’

‘Data doesn’t mean anything on its own. You have to be able to interpret it, relate it to the real world.’

A pot of cold coffee was sitting on the table next to the computer, so I warmed the bitter brown liquid in the microwave and toasted a couple of muffins and ate my breakfast waiting for the computer to boot up and pass me back out into the dark space of the network, which was beginning to feel more substantial to me than the room around, and as full of enchantment and tricks as a fast-hand conjuror.

I am deflated and left behind, made spare by the sheer pace and scale of the change.

I posted a short provocation on the WELL — a small uncommitted riff about the media being our chief source of shared values, and he, this someone I’m talking about, replied with a long treatise, the gist of which was that the situation wasn’t so bad because it at least implied that there was a shared set of values.

Hey, Mac, do you think it’s possible to make generational statements, or are generations created by the statements made about them?

The internet makes national borders irrelevant.

The screwy truth of the matter is that we speed through the years so fast we can hardly tell we’ve lived them. Even boys of seventeen worry about how to put the brakes on.

Playability is the thrill of anticipation driving a player forward. It’s the potent magic of immersion inside the world of the game. Playability is the ability to command the gaming character to act, without the character’s actions becoming predictable or pointless. It’s the accumulation of power with the goal in sight, but not made easy to reach. It’s the learning and rewarding process of continued feedback, the accumulation of an in-depth knowledge of bonuses and hidden dangers and powers and magic. Playability hints at the infinite time-space warp at the heart of the game. It promises mastery and escape; a magical, almost shamanistic power to the player, who by virtue of being (most likely) a young man in the midst of the ethereal, numb, dizzying hyperreality of our culture, senses that in ‘the real world’ he has none.

His CPU converts the letters to a sequence of 1s and 0s, spurts that sequence into the modem, which in turn converts it to a series of bleeps and tones, which slips into a phone line carrying it momentarily to a mainframe in North London, then around the country, and after that, as if no time has passed, across the Atlantic to a computer at CUNY, which switches it to some CPU in Chicago, then through Indiana and finally into the bank of modems at the waters edge in Sausalito, where its destination is noted, and the 1s and 0s of its constituent parts flown again across America through the ocean and back to the mainframe in North London from thence to its dinal rest on my screen.

Anyone under twenty-five is listening to House — machine music, technology’s true song.

‘The internet makes age, like, irrelevant,’ replies Mac, the smug bastard.

‘I’m beginning to think it’ll all turn out to be about money after all. Don’t you? Money and hype.’

‘Because in my psychology class I discovered I’m this extroverted intuitive type and in the future only people like me who are on the intuitive side will be able to shift context fast and keep up.’

‘So what’s the next big thing?’ There’s a rush for reservations on the bandwagon, but no one wants to have to build it first.

‘Work more, be freer! Ha! Why do people swallow that crap? Behind all that nineties dreck about teamwork and office campuses and free exchange of information is the familiar bullshit routine of working your butt off for someone else’s bottom line. The only really new thing is that no one has any job security any more.’

Here I am, teetering on the blade’s edge between dreams and the world. Between the bright lights in the distance and the Project towers close-up.

Chinese food is a tradition among Massachusetts Institute of Technology computer science majors stretching back to the fifties. Steven Levy devotes whole sections of his geek history, Hackers, to the early outings of MIT wireheads in Chinese restaurants. Forty years on, Chinese food is still the comp-sci cuisine of choice.

Geeks know how sad they are, but they don’t care.Being sad is a badge of geek strength and endurance. The transformation of computer buffs from lonely bedroom moles to triumphant geeks is one of the late twentieth century’s existential glories.

Admission: whatever I may think I’ve discovered about geek minds and geek thoughts, geek hearts will for ever remain a mystery to me.

‘That’s the dilemma with my computer obsession,’ he says lost in introspection. ‘You see, I want to give it up, but I’m afraid that the minute you pick something you’re not obsessive about is the minute you’re running your life backwards. The process doesn’t interest you any more. Only the goal, and because you picked the goal out some time in the past, you’re always looking back towards the moment when you picked it.’

What if? My mind whispers. What if the entire digital diaspora of broad-band info channels, of satellite links and instantaneous connections, of digi-cash and image flows, serves to do nothing more than flood the world with factoids, to weigh us down in the tide of trivial choice? What if it leaves us dazzled and dependent, common conscripts marking to the deceiving tune of money in some electronic re-boot camp, some world-wide Holy RAM-on Empire? What if it finally drowns us in its data?

Technology + business = the information economy, downsizing, global markets, instantaneous price adjustments, world products, niche marketing, surveillance.

Technology + popular culture = syndicated TV soaps and live news broadcasts and four trillion terrestrial channels and five million cable channels and home shopping and instant access to Internet Relay Chat.

Net users love a newbie to patronize, but once you reach a certain level of Internet experience something changes and you’re suddenly expected to be an expert. Intermediaries are not welcome on the Internet.

Note: As teenagers my generation didn’t protest against cars. We always thought the world would be blown to fragments long before it was stifled by petrol fumes and overlaid in asphalt. When we protested, which wasn’t very often, it was usually about Thatcher, the miners’ strike, Nicaragua or cruise missiles.

‘As the bandwidth gets bigger, it’ll fill up with more and more corporate advertising and virtual shopping and prono pics and snapshots of people’s holidays. And eventually absolutely everything in real life will have its counterpart on the wires.’

I find myself writing out the story of my technolife:

Woman falls in love with America.

Gets tangled up in technophilia. A brief period of wonderment follows.

She returns home (which never felt like home). She champions the cause, in her usual inefficient way.

No one much is interested. A nineteen-year-old boy is all.

So she runs back to America but finds everything changed.

She stiffens her lip. Or tries to. Typical Brit.

Returns home (which still doesn’t feel like home).

She is ugly, shop-soiled, disillusioned. Stiff-upper, stiff-upper, stiff-upper self-pity.

She thinks: what now?

‘I only ever get frightened when I take my eye away from the viewfinder, because then I’m actually a part of it.’

Suicide. I considered it once or twice, when I was a teen. Everyone does. Only later did it come to seem like a serious proposition. You can’t feel mortality when you’re fourteen. You have to imagine it. How many pills it takes, the psychedelic twirl in the bath, the drowning panic, the white light at the end of the tunnel, what you’d wear. Marilyn Monroe, Jim Morrison, Sylvia Plath, Kurt Cobain. Day-dreamed scenes against a Joy Division soundtrack, and a title sequence listing the people who’d be sorry . . .

I arouse myself with the thought that Moscow is like a game of Sim City gone wrong. You start with the archetypal metropolis: broad blocks zoned into commercial, residential and industrial areas, bounded by jugular avenues and six-lane boulevards. You scatter gargantuan boxes of apartments with their tiny, imbecilic windows, you carve out parks and public squares, you encourage the masses to play. And then you begin to have some fun. You pull funding from the infrastructure, you cut off the electricity supply, you make the water sour, you demolish part of the transport system and watch the population improvise. You close down the police force, put the hospitals into bankruptcy and sell off the city’s public utilities. You build rows and rows of shops hawking fatty sausages and Versace suits. You let factories bleed their chemicals into the air. You blacken legitimate enterprise and create a cash economy instead. You make it easy to evade taxes, jump the system. You ignore racketeering, bribery, and the omnipresence of violence and threat. You make life intolerably tough for almost everyone and obscenely luxurious for a tiny few. And finally, in a last magnificent gesture, you rename everything and insist that history be forgotten. And there you have it. Moscow at the end of the century. Sim City gone bananas.

Only Yevgeny isn’t disillusioned yet. Yevgeny is still listening to German industrial bands. Yevgeny is still inspired by The Hobbit.

This isn’t the future. This is somebody else’s present.

I’ve been away on my own so long I hardly know what’s real and what’s imagined any more.

It was as though I had found myself at the centre of a maze whose every turn led to the same blind alley.

I felt like an Eloi going down into the Morlock’s den, doomed but perfectly content all the same.

He’d be in his element here, for Mac is a true geek, in the nicest way. A man forever fascinated by the detailed possibilities technology brings, someone who likes to reach beyond the real world, beyond the confines of bodies and the mess of human interaction, to the stillness of machines. A man, like many men, who strains for the open sea, where the water is no longer churned to foam.

I thought about the Internet and it struck me that, whatever is written and said about the uncensored unpoliced space of Wiredworld, the actual experience of most of the people who use it is really very different.

For information is not in itself subversive, and knowledge is not necessarily power. On the contrary, information can be used to manufacture consensus, and ignorance is often more power than knowledge where it means not having to act.

I could probably live with death by dry martini.

From where I’m now standing it’s becoming clear what this recent love affair with the digital world really meant to me. It was a nostalgia trip. A form of time-travel. It drew me forwards into the future and pulled me back into my own adolescence, into the orgasmic feeling of possibility I sensed on that Amtrak train speeding towards San Francisco. I’ve been trying to achieve the impossible — to hold my past close and comforted in the distraction of other people’s future. All this time, running my life backwards, as though the future still belonged to me; which of course it doesn’t. For the future belongs to any of us only for the shortest while, from the instant we finally burst from our childhood skins to the instant we are bound back inside adult ones. For the shortest while we transcend our own mortality.

The Net is a Peter Pan machine, the screech and bubble of the modem always promising some new identity, some novel reconstruction, forever hinting at the future and drawing in its feint outlines.

Perhaps I have finally reached the still point and if I have, it is because I have travelled about so much and hunted down the same story in every place, and found that it is never the same. I’ve learned there is no single future, but an army of futures. And I’m no longer compelled to possess the single bright tomorrow. For now I’m sure that there’s no one technological arrow, piercing through the heart of everywhere. There is no cosy global village. And whereas once I saw tomorrow in an Amtrak train as it rushed towards its destination, I know now that it had no single destination. No-one is waving from the track. I am free to watch a hundred futures develop and evolve. And that is another kind of promise. Another kind of promiscuity.

This book is the result of four years’ experience. During that time many many people have made conscious or unconscious contributions to it. To those who were conscious my heartfelt thanks, and to those who were not, thanks too, and sorry it had to be that way.

In order to keep things running swiftly I have compressed the experiences of a number of years into the course of twelve months. A few names have been changed for reasons of privacy. Nancy is a composite, but all her parts are real. The intermission is a work of fiction. The title, Hard, Soft, and Wet is shorthand for hardware, software, and wetware, wetware being us.