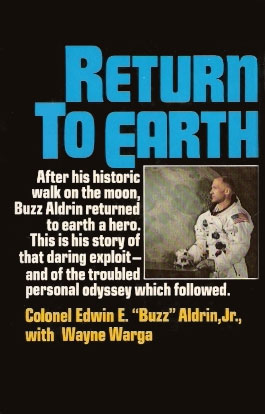

Return to Earth

Author: Buzz Aldrin with Wayne Warga

Release: 1973

Tagline: After his historic walk on the moon, Buzz Aldrin returned to earth a hero. This is his story of that daring exploit — and of the troubled personal odyssey which followed.

Publisher: Random House

Genre: Non-Fiction, Biography, History, Space Exploration, Engineering, Flight, Psychology

ISBN-10: 0394488326

ISBN-13: 978-0394488325

Synopsis: A book written by Buzz. American astronaut who became the second person to walk on the Moon. Aldrin graduated with honors from West Point in 1951 and subsequently flew jet fighters in the Korean War. Upon returning to academic work, he earned a Ph.D. in astronautics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, devising techniques for manned space rendezvous that would be used on future NASA missions including the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. Aldrin was selected for astronaut duty in October 1963 and in November 1966 established a new spacewalk duration record on the Gemini 9 mission. As backup Command Module pilot for Apollo 8, he improved operational techniques for astronautical navigation star display. Then, on July 20, 1969, Aldrin and Neil Armstrong made their historic Apollo 11 moonwalk.

Declassified by Agent Palmer: The Unknowns of Earth: A Book Review of Return to Earth by Buzz Aldrin

Quotes and Lines

I was up second in it, and during the ride, which lasted about two minutes, I had a peculiar feeling of loss. It wasn’t until I glanced down that I could understand the feeling. Down in the water was Columbia, our spacecraft: small, compact, and a virtual extension of each of us.

Just before we left the helicopter we ripped the Apollo 11 insignias off the isolation garments and handed them to the helicopter crew. It was spontaneous and a way of saying thanks.

When it was my turn to speak, I requested a moment of silence to pay tribute to Gus Grissom, Roger Chaffee, and Ed White, who had become to us symbols of the sacrifice put into space travel.

It would take a couple of years for it to become clear to me, but that day on the USS Hornet was actually the start of a trip to the unknown. I had known what to expect on the unknown moon more than I did on the familiar earth.

As was expected of each of us, I dutifully filled out an expense account for the trip. “From House, Tex., to Cape Kennedy, Fla., to the Moon, to the Pacific Ocean to Hawaii and return to Houston, Tex.” was how it read. How we traveled was by “Government Aircraft, Government Spacecraft, USN Hornet, USAF Plane.” Total expense reimbursement” $33.31. This amount took care of mileage in and around Cape Kennedy during the time immediately prior to lift-off. The expense account is one of my most treasured souvenirs of the trip and sits framed in a place of honor in my study.

Although it was never stated officially, it went without saying that rivalries or arguments within the astronaut corps were not discussed in public because it would tarnish both our image as individuals and the image of the space program.

Public speaking takes practice and I was about to get plenty. Practice, in my case, may not have made me perfect, but at least I’m bearable. I’m even used to it and, on occasion, find it stimulating, but it’s still not a case of step-on-my-foot-and-my-mouth-will-open.

I felt like saying, “Don’t thank me, let me thank you.”

The parade consisted of the Montclair drill team, a marching band, and several cars–one of them containing three elderly people and the sign WE TAUGHT BUZZ. Three people from long ago who had encouraged me to study when I was at an impressionable age. I hoped that my success had somehow touched them and that they shared in it.

Scientific exploration implies investigating the unknown. The result can never be wholly anticipated. Charles Lindbergh said, “Scientific accomplishment is a path, not an end; a path leading to and disappearing in mystery.”

The three of us discussed this and informed both NASA and the State Department that we were going on the trip to demonstrate goodwill to all the people in the world and to stress that what we had done was for all mankind.

I must have looked terribly distressed at the news because Bill Carpentier, who had been our faithful and likeable physician during the long postflight isolation, and was our physician on the tour, took me aside early that evening to ask if I was all right.

“I don’t think so, Bill. I think I’m overwhelmed.”

It is curious what one remembers and observes during a trip such as this. All of us later mentioned the tea, simply because it was the first tea we had attended at which Scotch or champagne were not the only liquid served. The evening receptions and dinner also included liquor, but that was a natural occurrence. My prevailing memory of the whole trip is that there was liquor everywhere.

We were caught in the ebb and flow of a changing world within a world.

November 5: We left Tokyo at 2:00 P.M. to begin the long flight to Washington with a 2:00 A.M. stop to refuel in Anchorage. I slept fitfully, watched a movie, and ate. Neil, Mike, and I were sleeping when we arrived in Anchorage, but Joan, Jan, and Pat got off the plane and threw snowballs. The three of them were friendly before Apollo 11, but by now they were fast friends–all that had happened since the day we splashed down in the Pacific has strengthened their bond. Their husbands were slowly drifting apart, while they grew closer. It is a peculiar irony, but out wives remain close while I see Mike infrequently and Neil hardly ever.

Teenagers, I have since discovered from my three, wear their parents into cooperation more by attrition than by logic.

Attached to the trigger is a camera, and I came back with a set of gun camera film of my first MIG. It turned out to be a rather historic set of pictures because they included the ejection sequence, the first pictures of the war to show a pilot bailing out. I didn’t think I had gotten pictures of the ejections but I had. They appeared a week later in Life magazine and went on to become one of the more rare photographs of the Korean War.

My elation must have been a bit too obvious because on the last night during a beer-drinking session one of my classmates, a captain I respected a good deal, took me aside and offered some advice. He was older and senior to me–I was a first lieutenant and an eager audience. He said, in effect, that I was too competitive, too insensitive to others, too determined to be the best, and that if I didn’t watch it I’d end up with a reputation as a hotshot egotist. He then said he felt I had great talent and potential and that as my friend he didn’t want to see me ruin my chances.

I zeroed in on the idea of man controlling rendezvous with space vehicles. I knew there were computers and other sophisticated means of rendezvous being planned but what if they failed at the last minute? Success would depend on the amount of knowledge the astronaut had about man-controlled rendezvous.

The title of my thesis eventually became “Line of Sight Guidance Techniques for Manned Orbital Rendezvous.” It is some of the most tedious reading on record but it fulfilled its purpose because it subsequently proved its practical application in space. That I happened to be the astronaut in space at the moment the theory needed to be tested was a stroke of divine good luck.

It is an old and effective–not to mention comforting–military tradition to foregather and insulate at the time of death. We were no longer strictly in the military, of course, but in the untried and unfamiliar world of space travel, and the specter of death that hung uneasily about us all. There was always the possibility, however remote, of death in space. Thus we became even more insular and protective.

My feeling is that the unit still could have been tested and that one of the reasons it was dropped had to do with the interagency politics. I became aware of these overtones when I first came to Houston in the Air Force to work with the NASA people on rendezvous. It was never stated outright, but it was nevertheless generally conceded that NASA wanted to do it alone and didn’t particularly welcome any collaboration from the Air Force. I went one day to a rendezvous meeting to explain some of the theories from my thesis and midspeech I realized my NASA audience wasn’t listening. Such things are, I am told, familiar occurrences within other government agencies, but I nevertheless find such behavior stupid, annoying, and usually self-defeating.

The last thing Jim and I did after we finished suiting up was to attach the two signs we had made to our backs. Jim would precede me walking to the capsule. His sign said THE and mine said END.

I never discussed this with any of the others who attended that meeting, but I for one wasn’t at all certain I wanted to be on the first flight to land. Instincts send messages just as computers do, but the trouble with instinct is that we either ignore or challenge it instead of investigating it. My instinct was murmuring quietly that my own scientific interests might be better served by one of the longer, more adventurous missions later on and, if I went on the first flight, it might turn out a bit difficult to get back into the swing of the astronaut business again. My instincts eventually proved to be guilty of a major understatement.

That night, perhaps overstating it a bit, Joan made the following entry in the diary she sporadically kept:

Buzz went to work this morning without a job and came home tonight LM pilot of Apollo 11, the first lunar landing. So it is really happening and I am scared.

I have a marvelous faculty for putting out of my mind those things I don’t want to face up to, but it no longer works. It was a day, the first of many, I’ll bet, o walking on eggs, or normalcy tinged with hysteria. I wish Buzz were a truck driver, a carpenter, a scientist–anything but what he is. I want him to do what he wants, but I don’t want him to. He is such a curious mixture of magnificent confidence bordering on conceit and humility, this man I married.

On Friday, January 10:

Buzz spent much time explaining to me the various methods planned for obtaining rocks from the moon. Seems it’s not just a matter of picking them up and dumping them in a sack. That’s about as far as I understood. Ah, the complications of the space age!

On Thursday, January 16:

Broke out with blotches last night, which still persist today. I’m covered with pancake makeup and jumpy. Nerves. It I’m like this now, what will I be like when it really happens?

Apollo 10, the dress rehearsal for our lunar landing, lifted off May 18, 1969. Tom Stafford, Gene Cernan, and John Young flew a perfect flight. The only difficulty involved certain repercussions when gene, in lunar orbit, discovered an error had been made and radioed back, for all to hear, “Son of a bitch!” Tom then set another precedent when a camera balked saying, “Ah, shit.” Besides preparing the way for our flight, Tom and Gene were also establishing the reality of astronauts–we were, after all, human.

Our concentration on what lay ahead was total. We saw ourselves as the objects of a gigantic, intense effort, and not at all as individuals.

The next morning would be July 16, 1969, a day that would go down in history. Actually, it was a day already noted in history, though few remember it or knew of it at the time. On July 16, 1945, on a barren and secret piece of land in New Mexico the first atomic bomb was detonated.

Going to the moon was easy compared with speaking to a joint session of Congress. I came to look back on this brief speech–over which I had slaved for hours–as the moment I realized that my life would never again be the same and that somehow I was unequipped for what would come.

Before we began to make a more complete check of the LM, we received data from earth for what is called the trans-earth injection, a burn to get us out of lunar orbit and on our way back to earth. There were fifteen to twenty such possibilities, and one by one as they came up from Houston we copied them down and checked them, and the data was then ready for insertion into our computer in case of any emergency. This system replaced the Return to Earth computer program we had decided to discard a year earlier.

Rendezvous had come a long way since I first started contemplating it at MIT. Looking back on it now, I honestly believe that the contributions I made to the space program in the development of pilot rendezvous techniques surpass even my part in Apollo 11.

The voyage to the moon was conducted with nearly half a second of the flight plan. Of all the various midcourse corrections it was possible to make en route to and from the moon, we had used only two. The training and preparation was such that even the unfamiliar surface of the moon was very nearly what we had been led to expect. I realized I wasn’t in the simulator and it was a good bit more real, but virtually nothing was unexpected. The extensive studies and preparations were that good.

Twelve American men have now visited the surface of the moon. If the twelve of us have any one viewpoint in common, it is that unlike most men we have a special concept of the earth. We have seen it from space as whole and bright and beautiful; we have seen it from the surface of the moon as not very large and somehow vulnerable. With all its imperfections, it is a great place to come from and an even greater place to go back to.

I am by nature so deliberative that I did not notice when my deliberations turned to procrastination and indecision.

I was suffering from what the poets have described as the melancholy of all things done.

I suppose the portrayal we received in Life and subsequently in nearly all the media helped the space program a great deal. Unfortunately, nearly all of it had us squarely on the side of God, Country, and Family. To read it was to believe we were the most simon-pure guys there had ever been. This simply was not so. We may have regularly gone to church, but we also celebrated some pretty wild nights.

It is my devout wish to bring emotional depression into the open and so treat it as one does a physical infirmity.

Few men, particularly those who are motivated toward success, ever pause to reflect on their lives. They hurry forward with great energy, never pausing to look over their shoulders to see where they have been. It a man does this at all, it is usually near the end of his life, and it happens only because there is little else for him to do.

I trusted nothing to luck, because luck was noticeable by its absence. So was fate. My feeling was that if I went down the hall to go to the bathroom, luck and fate would get together and see that I left the bathroom with both my shoes wet.

Instead of retiring to my rocking chair–it was broken, anyway–I plunged into furious activity. Cartons and cartons of my lifelong files were transferred from my office to our garage, and completely filled it. There was no room for a car, and only Andy’s motorcycle fit. The files needed to be culled and placed in order–an undertaking that proved much larger than I suspected. I have yet to complete it and it has evolved into a sort of ritual. I decide first to clean off my desk, which as a tendency to look as though there has been an explosion in a paper factory. By the time the desk is clean, the mail answered, the checkbooks balanced, and the filing done, it is the end of the month, and gradually it all starts over again.

I participated in what will probably be remembered as the greatest technological achievement in the history of this country. I traveled to the moon, but the most significant voyage of my life began when I returned from where no man had been before.

When I began this book I had two intentions. I wanted it to be as honest as possible and to present the reality of my life and career not as mere fact but as I perceived the truth to be. The second and more important intention was that I wanted to stand up and be counted.