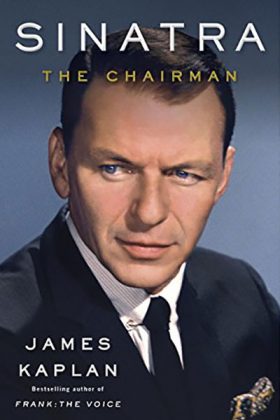

Sinatra: The Chairman

Author: James Kaplan

Release: October 27, 2015

Publisher: Doubleday

Genre: Biography, Music, Entertainment, Movies, History

ISBN-10: 0385535392

ISBN-13: 978-0385535397

Synopsis: The story of Frank Sinatra, “Ol’ Blue Eyes” continues in Sinatra: The Chairman where Sinatra: The Voice left off. Picking up from the day after he claimed his Academy Award in 1954 and his reemergence to top recording artist. Sinatra’s life post-Oscar was astonishing in scope and achievement and, occasionally, scandal, including immortal recordings almost too numerous to count, affairs ditto, many memorable films (and more than a few stinkers), Rat Pack hijinks that mesmerized the world with their air of masculine privilege, and an intimate involvement at the intersection of politics and organized crime that continues to shock and astound with its hubris.

Declassified by Agent Palmer: A Swingin’ Book Report on Sinatra: The Chairman by James Kaplan

Quotes and Lines

But the secret was that he was still yearning. (He would always yearn, even after he had gained all the world had to offer.)

Riddle wrote of his work with Sinatra, “Most of our best numbers were in what I call the tempo of the heartbeat . . . Music to me is sex–it’s all tied up somehow, and the rhythm of sex is the heartbeat.”

But his features are cleanly sculpted, his eyes avid and riveting: this is now a mature face, one in which liquor and cigarettes and heartbreak have made deep inroads. And fame. It’s impossible not to notice that this would-be presidential assassin looks fresh from the poolside in Palm Springs: he has a deep tan and a sleek, self-pleased aspect that a contract killer’s backstory doesn’t quite account for.

…human beings are complicated creatures and that no human was more complicated than Frank Sinatra. In the year of 1954, as Frank regathered the vast power he’d lost, he also achieved new heights of arrogance. There was Sinatra, and then there was everybody else. He knew it, and the world knew it.

If Not as a Stranger was an odd choice for Stanley Kramer, it was no less odd for the third-billed Sinatra. “Why did Frank Sinatra bother to make this movie? Tom Santopietro asks. “Did he simply want to keep working continuously on A-list productions in order to build upon the success of From Here to Eternity and Young at Heart? Was it his well-known fear of being bored?”

In the midst of a career comeback, momentum was everything. He couldn’t afford to sit around and wait for the perfect movie role to pop up.

He was searching. And in some ways flailing.

Time quoted “one of his best friends,” who said, sounding an awful lot like Sammy Cahn, “There isn’t any ‘real’ Sinatra. There’s only what you see. You might as well try to analyze electricity. It is what it does. There’s nothing inside him. He puts out so terrifically that nothing can accumulate inside.”

Sinatra’s terrific output came straight from the formidable chaos brewing within.

Cool looked good to Frank Sinatra. Unattainable, but good.

“…But that’s Sinatra. He could sing with the grace of a poet, but when he’s talking to you, it’s Jersey!” – Milt Bernhart

(The illusion of stardom is always the illusion of ease.) – Jeanine Basinger

He was Frank Sinatra. He was, Peggy Connelly recalled, “always on his way somewhere else in his mind, even while he was looking you in the eye. Someone once said he had no ‘now.’ He was never satisfied to be where he was.”

With Sinatra, the sublime and the ridiculous, the exquisite and the coarse, alternated so quickly and frequently that it’s useless to try to reconcile them.He wasn’t one thing or the other; he was both, and then a moment later he was something else again.

He was detached and ironic, imbued with a quality known in Italian as menefreghismo–in translation, not giving a fuck. -He = Dean Martin

“I’m a real stickler for perfection in my work, and in most other people’s work, too,” Sinatra had told Edward R. Murrow. “I find myself picking whatever I do apart. Which I do believe is quite healthy.”

At the end of October, Frank made front-page news by denouncing “the most brutal, ugly, degenerate, vicious form of expression it has been my displeasure to hear.” He was referring to rock ‘n’ roll. According to the Associated Press, Sinatra had written the words in a piece for a Parisian magazine called Western World. The AP report quoted Frank further:

It fosters almost totally negative and destructive reactions in young people. It smells phony and false. It is sung, played and written for the most part by cretinous goons and by means of its almost imbecilic reiterations and sly, lewd–in plain fact dirty–lyrics . . . manages to be the martial music of every sideburned delinquent on the face of the earth.

This rancid smelling aphrodisiac I deplore. But, in spite of it, the contribution of American music to the world could be said to have one of the healthiest effects of all our contributions.

He moved on a bubble of agitation, always with a pack, searching for the next amusement. Boredom was the enemy; and sleep, death’s counterfeit. And solitude.

“Let’s just say that the Kennedys are interested in the lively arts, and that Sinatra is the liveliest art of all,” Peter Lawford would ell a reporter in 1960.

“This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

-The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962)

“The Rat Pack embodied Hollywood’s most elemental mth, its deepest unspoken appeal–that as its final reward, fame offered a life without rules, without the constraints of fidelity, monogamy, sobriety, and the dreary obligation to show up at a job every morning,” writes the political journalist Ronald Brownstein.

But as Sinatra’s Columbia Records rabbi and close friend, the late Manie Sacks, had learned to his sorrow, nothing–not friendship, not love, not loyalty–was more important to Frank than his career. Once he decided he wanted something anyone who opposed it was the enemy.

And yet there was a hollowness to all this misbehavior–and not just morally speaking. The Summit’s act at the Sands was infantile, the grown-up equivalent of fart jokes. It was a reaction to the profound national torpor of the 1950’s: the Rat Pack “depended for its vitality on what Gore Vidal has called ‘the great national nap’ of the 1950s–at times Frank and ‘the clan’ seemed the only people awake after 10:00 p.m.,” writes professor and cultural critic T. H. Adamowski. The Summit was a declaration of superiority–except that the most superior one of all, the Leader, was himself a whirl of chaos, centerless. The emperor was not only naked but manic-depressive.

Leisure never sat well with him. As he told a reporter in 1957, “I’ve just got to be busy, that’s all. I take a vacation for five days and I’ve had it. I get restless.” His natural impatience quickly led to devilry of all sorts, and self-dislike always lurked in the shadows. Heavy drinking followed inevitably, and with drinking came the release of anger.

“People who call me controversial are those who don’t agree with me.” – Frank Sinatra at a press conference in Tokyo, April 20, 1962.

Asked whether he was trying to create a “new Sinatra image” of kindness and patience to replace his controversial publicity, Sinatra said:

“I don’t really think so. People who call me controversial are those who don’t agree with me. I plan to remain controversial because we won’t make progress unless we’re controversial and rebellious from time to time.”

For Frank, confession is akin to apology; an unnatural act.

I don’t think age has as much to do with it as does physical condition. In other words, as long as I stay in shape, I should be able to keep singing. My voice is as good now as it ever was. But I’ll be the first to know when it starts to go—when the vibrato starts to widen and the breath starts to give out. When that happens, I’ll say goodbye. I wouldn’t want to make a recording and have to listen to it 20 years from now with those symptoms turning up. I can’t kid myself into thinking my voice will be as strong or my enthusiasm as buoyant a few years from now.

I don’t believe in self-indulgence, anyway. In all my years as a performer, I’ve believed in taking only the nucleus of an act, that part which is so good, then getting off quick. I don’t do a long time on stage. That goes for my life, too.

“This is the great age of candor,” Paul Newman told Playboy in 1983. “Fuck candor.”

“That’s what makes entertaining an interesting business. No day is the same. Generally, what performers look for most is variance. If not, they should. It keeps you and the audience interested.” – Frank Sinatra

Frank himself vouchsafed no comment about future plans except “I like to keep busy. Solitude is very depressing. I need activity.”

[Norman] Mailer titled his surging , bulging, coruscating essay “Ego,” in honor of Ali, whom he dubbed America’s Greatest in that department–and with whose ego he unsurprisingly managed to conflate his own. “Everything we have done in this century, from monumental feats to nightmares of human destruction,” he wrote, “has been a function of that extraordinary state of the psyche which gives us authority to declare we are sure of ourselves when we are not.”

In the period between March 26, 1954, the day after he won the Oscar for From Here to Eternity, and June 13, 1971, the date of his retirement concert in Los Angeles, Sinatra made forty-six albums, many of them great. In the period between his second comeback, in 1973, and the end of his career–he performed his final concert in 1995–he made seven albums, a couple of them very good.

Between 1954 and 1971, he starred in thirty-two movies; after 1973, he starred in two, one of them made for television.