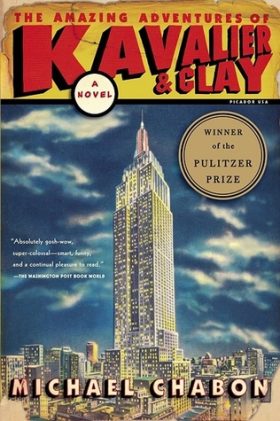

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay

Author: Michael Chabon

Release: September 19, 2000

Publisher: Random House

Genre: Fiction, Historical Fiction

ISBN-10: 0679450041

ISBN-13: 978-0679450047

Main Character(s): Joe Kavalier, Sam Clay, Rosa Saks

Synopsis: It is New York City in 1939. Joe Kavalier, a young artist who has also been trained in the art of Houdini-esque escape, has just pulled off his greatest feat to date: smuggling himself out of Nazi-occupied Prague. He is looking to make big money, fast, so that he can bring his family to freedom. His cousin, Brooklyn’s own Sammy Clay, is looking for a collaborator to create the heroes, stories, and art for the latest novelty to hit the American dreamscape: the comic book. Out of their fantasies, fears, and dreams, Joe and Sammy weave the legend of that unforgettable champion the Escapist. And inspired by the beautiful and elusive Rosa Saks, a woman who will be linked to both men by powerful ties of desire, love, and shame, they create the otherworldly mistress of the night, Luna Moth. As the shadow of Hitler falls across Europe and the world, the Golden Age of comic books has begun.

Declassified by Agent Palmer: The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay is Brilliant (A No Spoiler Book Review)

Quotes and Lines

We have this history of impossible solutions for insoluble problems. – Wil Eisner, in conversation

Like all of his friends, he considered it a compliment when somebody called him a wiseass. (He = Clay)

But like most natives of Brooklyn, Sammy considered himself a realist, and in general his escape plans centered around the attainment of fabulous sums of money.

“‘Forget about what you are escaping from,’” he said, quoting an old maxim of Kornblum’s. “‘Reserve your anxiety for what you are escaping to.’”

“Never worry about what you are escaping from, he said. “Reserve your anxieties for what you are escaping to.”

“People only notice what you tell them to notice,” he said. “And then only if you remind them.” – Kornblum

Gossips, busybodies, and kibitzers were the fiends of her personal demonology. She was universally at odds with the neighbors, and suspicious, to the point of paranoia, of all visiting doctors, salesmen, municipal employees, synagogue committeemen, and tradespeople.

All of this left him hardened, battered, rumpled, and addicted to the making of money, but not, somehow, embittered. – Anapol

Sammy glared at Ashkenazy, not because Ashkenazy had insulted his work–no one was ever more aware of his own artistic limitations than Sam Clay–but because Sammy felt that he was standing on the border of something wonderful, a land where wild cataracts of money and the racing river of his own imagination would, at last, lift his makeshift little raft and carry it out to the boundless freedom of the open sea.

Joe gave up trying to think like, trust, or believe in his cousin and just walked, head abuzz, toward the Hudson River, stunned by the novelty of exile.

Her entire discourse with him appeared to consist solely of animadversion and invective.

It was, in part, a longing–common enough among the inventors and heroes–to be someone else; to be more than the result of two hundred regimens and scenarios and self-improvement campaigns that always ran afoul of his perennial inability to locate an actual self to be improved.

In the immemorial style of young men under pressure, they decided to lie down for a while and waste time.

It was not that Joe felt at home in New York. That was something he never would have allowed himself to feel. But he was very grateful to his headquarters in exile. New York City had led him, after all, to his calling, to this great, mad new American art form. She had laid at his feet the printing presses and lithography cameras and delivery vans that allowed him to fight, if not a genuine war, then a tolerable substitute.

…work that Deasey had long since concluded was only “a long, spiraling chute, greased with regular paychecks, to the Tartarus of pseudonymous hackdom.”

Neither of the cousins was much for parties. Though Sammy was mad for swing, he could not, of course, dance on his pipe-cleaner legs; his nerves killed his appetite, and at any rate, he was too self-conscious about his manners to eat anything; and he disliked the flavor of liquors and beer. Introduced into a cursed circle of jabber and jazz, he would drift helplessly behind a large plant. His brash and heedless gift of conversation, by means of which he had whipped up Amazing Midget Radio Comics and with it the whole idea of Empire, deserted him. Put him in front of a roomful of people at work and he would be impossible to shut up; work was not work for him. Parties were work. Women were work. At Palooka Studios, whenever there occurred the chance conjunction of girls and a bottle, Sammy simply vanished, like Mike Campbell’s fortune, at first a little at a time, and then all at once.

“Don’t be smart, it’s unattractive in a man.” – Rosa to Joe

To get paid vast sums for wasting one’s life, in her view, only added to the cosmic tallying of wastefulness. Most maddening of all to Sammy was the way that, in the face of the sudden influx of money, Ethel steadfastly refused to change any element of her life, except to shop for better cuts of meat, buy a new set of carving knives, and spend a relatively lavish amount on new underwear for Bubbie and herself.

When they had first started going out, he was so absorbed by his work that he rarely had time for meals, existing quite mysteriously on coffee and bananas, but as Rosa herself, to her considerable satisfaction, had begun to absorb Joe more and more, he had become a regular guest at her father’s dinner table, where there were never fewer than five courses and three different varieties of wine. His ribs no longer stuck out, and his skinny little-boy’s behind had taken on a manlier helf.

The true magic of this broken world lay in the ability of the things it contained to vanish, to become so thoroughly lost, that they might never have existed in the first place.

One of the sturdiest precepts of the study of human delusion is that every golden age is either past or in the offing.

“I’m tired of fighting, maybe, for a little while. I fight, and I am fighting some more, and it just makes me have less hope, not more. I need to do something . . . something that will be great, you know, instead of trying always to be Good.” – Joe

The systems that controlled the motion, sound, and lighting of Democracity and its companion exhibit, General Motors’ Futurama, were quite literally the dernier cri of the art and ancient principles of clockwork machinery in the final ticking moments of the computerless world.

What would she be saying if she did? That she wanted to marry him? For ten years, at least, since she was twelve or thirteen, Rosa had been declaring roundly to anyone who asked that she had no intention of getting married, ever, and that if she ever did, it would be when she was old and tired of life. When this declaration in its various forms had ceased to shock people sufficiently, she had taken to adding that the man she finally married would be no older than twenty-five. But lately she had been starting to experience strong, inarticulate feelings of longing, of a desire to be with Joe all the time, to inhabit his life and allow him to inhabit hers, to engage with him in some kind of joint enterprise, in a collaboration that would be their lives.

She closed her eyes and tried to recite a snatch of Buddhist prayer her father had taught her, claiming it had a calming effect. It had little apparent impact on her father, and she wasn’t even sure she had the words right. Om mani padmi om. Somehow it did make her feel calmer.

He tried to be stern and friendless but was an inveterate kibitzer.

…explorers invariably give their names to the places that haunt or kill them.

The defeat of those actual world-devouring supervillains, Hitler and Tojo, along with their minions, had turned out to be as debilitating to the long-underwear hero trade as the war itself had been an abundant source of energy and plots; it proved to be hard for the cashiered captains and supersoldiers, on their return from tying Krupp artillery into half-hitches and swatting Zeros like midges over the Coral Sea, to muster the old pre-1941 fervor for busting up rings of car thieves, rescuing orphans, and exposing crooked fight promoters. At the same time, a new villain, the lawless bastard child of relativity and Satan, had appeared to cast its roiling fiery pall over even the mightiest of heroes, who could no longer be entirely assured that there would always be a world for them to save. The tastes of returning GIs, who had become hooked on the regular shipments of comic books provided them along with candy bars and cigarettes, turned to darker, more “adult-oriented” fare: true-crime comics had their vogue, followed by horror tales, Westerns, science fiction; anything, in short, but masked men.

Rosa shook her head. It seemed to be her destiny to live among men whose solutions were invariably more complicated or extreme than the problems they were intended to solve.

The usual charge leveled against comic books, that they offered merely an escape from reality, seemed to Joe actually to be a powerful argument on their behalf. He had escaped, in his life, from ropes, chains, boxes, bags, and crates, from handcuffs and shackles, from countries and regimes, from the arms of a woman who loved him, from crashed airplanes and an opiate addiction and from an entire frozen continent intent on causing his death. The escape from reality was, he felt–especially right after the war–a worthy challenge.

The newspaper articles that Joe had read about the upcoming Senate investigation into comic books always cited “escapism” among the litany of injurious consequences of their reading, and dwelled on the pernicious effect, on young minds, of satisfying the desire to escape. As if there could be any more noble or necessary service in life.

Hope had been his enemy, a frailty that he must at all costs master, for so long now that it was a moment before he was willing to conceded that he had let it back into his heart.

Now he had been unmasked, along with Bruce and Dick, and Steve and Bucky, and Oliver Queen (how obvious!) and Speedy, and that security was gone for good. And now there was nothing left to regret but his own cowardice.

“I’m much too old to be happy, Mr. Clay. Unlike you.” – Deasey

I have tried to respect history and geography wherever doing so served my purposes as a novelist, but wherever it did not I have, cheerfully or with regret, ignored them.

Finally, I want to acknowledge the deep debt I owe in this and everything else I’ve ever written to the work of the late Jack Kirby, the King of Comics.

Michael Chabon’s grandfather was a typographer who worked in a New York City plant where, among other things, comic books were printed.